A hidden ureteral metastasis that originated from prostate cancer: a case report and literature review

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is now plaguing the health of middle-aged and aged men as the second most diagnosed malignancy in men worldwide. The incidence of PCa is lower in Asia than in Europe and the US, but the growth rate is much higher in Asia in recent years. The growth rate of the incidence of PCa in China was 2.1% from 1988 to 1994, and was 13.4% from 1994 to 2002 (1). Approximately 20% of PCa patients develop metastatic disease (2), and the most common metastatic sites of PCa are regional lymph nodes, bones, distant lymph nodes, lungs and liver (3). However, metastasis from primary PCa to the ureters is extremely rare. This study reports a hidden ureteral metastasis originating from PCa and reviewed relevant literature.

Case presentation

Clinical history and surgery

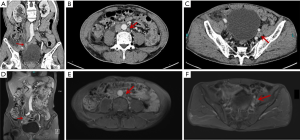

A 61-year-old male was admitted to our department because of having right flank pain and a fever for 10 days. Hematuria was not present. There was a palpable mass at the right lower quadrant and right renal percussive pain. Computed tomography urography (CTU) showed right hydroureteronephrosis obstructed by soft tissue in the right ureter (3 cm × 1 cm), and retroperitoneal and left iliac vascular area lymphadenectasis (Figure 1A-C). Digital rectal examination was refused by the patient due to his physical weakness.

Ureteroscopy was performed to determine the nature of the soft tissue. However, it was surprising that the ureteral catheter (thinner than a double J stent) had easily passed through with no visible detection at the middle and lower parts of the right ureter by a ureteroscope. We were unable to continue to push the ureteroscope forward because of its structure, which became thicker moving from the distal to the proximal direction. While inserting a double J stent, we found it hard to insert it completely through the ureteral lumen. We were afraid of tearing the ureter and finally gave up on inserting the double J stent. Then, magnetic resonance hydrography (MRH) was performed (Figure 1D-F), which produced a similar result as that of CTU. In addition, transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) was highly suspected by imaging experts and us. The TNM stage was hypothesized to be TXN2M0.

In the next few days, the patient was deteriorating in both physical and mental status. He felt a frequent pain in the right flank and ate less; worst of all, he had destructive feelings. He was eager to be treated surgically as soon as possible. His relatives also requested us to remove the ureteral mass. Therefore, excision of his right ureteral mass (Figure 2) was performed, and all the aforementioned symptoms were taken into consideration during surgery. We found that the tumor was wrapped around the ureter, and there was were no enlarged lymph nodes beside it. The intra-operative frozen section of the mass was determined to be invasive carcinoma. Then, radical nephroureterectomy (RNU) with bladder cuff removal was performed, as it is the standard treatment of TCC patients, and because there was normal renal function on the unaffected side (4).

Pathological features

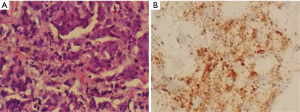

Another surprising finding was the pathological examination revealed right ureteral carcinoma, which indicated a metastatic PCa (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical staining showed that the cells were positive for Ki67 (approximately 20%), PSA and P504S (Figure 3B). Cancer tissue had infiltrated the full-thickness of the ureter wall, and the Gleason score was 9 (5+4), grade V.

Subsequent treatment

The patient was informed of the results and was advised to finish relevant medical examinations in the local hospital, including measuring his prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level as well as undergoing prostatic MRI and bone scintigraphy. The total PSA (tPSA) level was 309.70 ng/mL, and prostate Prostatic MRI showed evidence of PCa with a great possibility of multiple bone metastases in the pelvis. Bone metastasis at the femoral head was confirmed by bone scintigraphy.

One-week focal radiotherapy was performed immediately after that procedure, and the patient was managed with intermittent androgen deprivation (IAD) therapy using bicalutamide and goserelin. The PSA level kept decreasing to less than 0.2 ng/mL in the fourth month of IAD therapy. The patient now feels better, and we will focus on regular follow-up to his condition.

Discussion

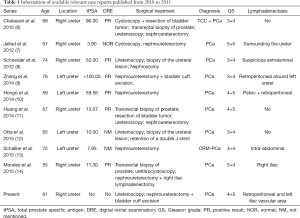

Approximately 43 case reports of PCa with ureteral metastasis have been reported in the last century (5). We searched PubMed and found 9 available studies from 2010 to 2015 (6-14) (Table 1). Of these cases, eight cases were diagnosed with metastatic PCa, one of which was castration-resistant metastatic PCa. One case was metastatic PCa with TCC (6). These patients were aged from 55 to 76 years at diagnosis, with a median age of 67 years. All GS grades scores were no less than 7.

Full table

Diagnosis and surgical treatment

Approximately 90% of ureteral malignancies are TCC (15). Metastatic tumors to the ureters are fairly rare, and relatively common primary tumors are originated in the breast, colon, lymph and lungs (5). However, all possible diagnoses should be considered when confronting ureteral masses, including stones, blood clots, TCC, metastatic tumors and lymphadenopathy (6,10) .

Metastatic PCa was considered a differential diagnosis of a ureteral mass mainly because of abnormal DRE and PSA levels and regardless of the only exception of a case with normal results (7). Therefore, DRE and PSA screening are necessary for male patients with a ureteral mass. Biopsy is the only way of uncovering the nature of a ureteral mass despite a high suspicion of PCa. The study of Chalasani et al. reported a patient with a right ureteral mass and PCa, but the biopsy result showed TCC (6). Therefore, ureteroscopy and biopsy are standard inspection means for a ureteral mass.

In the present patient, the middle and lower parts of the ureteral lumen were complete and smooth from the perspective of ureteroscopy, which is considered unusual for most other cases of PCa with ureteral metastasis and tumors exposed to the lumen. Therefore, we could not obtain suspicious visible tissue for pathological diagnosis by ureteroscopy. Percutaneous biopsy is used widely to obtain suspicious tissue, but we seldom perform this type of biopsy to detect the nature of a ureteral mass, especially for the lower part. Because ureters are thin and sometimes twisty, it is difficult to localize position accurately to the lower part of the ureter using an ultrasound machine. Then, neoadjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy was put forward as one of the first potential therapies, but it was eventually negated for the following reasons: first, the patient’s sensitivity to this therapy was unknown; second, the condition of the patient was deteriorating, and he was probably unable to tolerate the chemotherapy; third, he and his relatives refused this kind of therapy. RNU with bladder cuff removal was finally performed as a thorough treatment considering its intra-operative frozen result. However, it is necessary to reflect on whether this procedure was the best treatment for the patient.

Otta et al. noted that treatment of ureteral metastasis of PCa includes nephroureterectomy, segmental resection, and conservative approaches (12). However, segmental resection is not a good idea for the patient because he has a scar physique, which will possibly cause ureteral stricture again. Furthermore, nephrostomy with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is another infeasible approach because of the uncertain nature of the mass of our patient before the pathological examination results. Additionally, Denis and Hiroshi reported patients developing ureteral metastasis of PCa during ADT, which indicated the potential risks of conservative approaches (10,13). Thus, as far as we are concerned, RNU with bladder cuff removal was the best treatment for this patient. We further suggest that the suspicious ureteral malignancy of an unknown nature should be resected as soon as possible to reduce the risk of metastasis or further metastasis. The patient underwent CTU and MRH preoperatively. The results showed no detection of bone metastasis preoperatively, but the results were positive for bone metastasis postoperatively. There were two possible causes for these results: (I) bone metastasis did not exist preoperatively; or (II) bone metastasis was too obscure to be detected by imaging examinations preoperatively, but developed quickly. Therefore, we decided bone scintigraphy was necessary for detecting the bone metastasis originating from PCa.

ADT

When the patient was diagnosed with metastatic PCa, we suggested that he undergo ADT, which was widely used all over the world. Chemohormonal therapy was not considered because it is still not carried out in our hospital, so we lack such experience. However, the patient could have undergone an IAD therapy or continuous androgen deprivation (CAD) therapy, and we informed him about the difference between IAD and CAD (16). The patient was only 61 years old, and he expressed high expectations regarding social activity and physical capacity. Therefore, he chose IAD and wanted to restore his physical capacity and participate in social activities during the period of drug withdrawal.

Pathway of cancer metastasis

There are several hypothetical ureteral metastases of PCa including implantation by instrumentation, arterial emboli, direct extension of the tumor around the intravesical ureter and venous or lymphatic dissemination in a retrograde manner (17,18). It was hypothesized that the lymphatic circulation of the ureter is segmental and drains diagonally or transversely, and there is no continuous longitudinal lymphatic network draining directly from the prostatic area (19). In our case, venous and lymphatic dissemination are more possible. Retroperitoneal and left iliac vascular area lymphadenectasis of the patient indicate lymphatic dissemination, while multiple bone metastases are the result of venous dissemination. We found that there were no enlarged lymph nodes around the ureteral tumor and no tumors in the bladder. So, it is reasonable to believe that lymphatic and direct metastasis are excluded, and venous dissemination is the most plausible metastatic pathway of the ureteral metastatic tumor.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2017.05.18). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1995-2005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui E, Mumtaz FH, Gelister J. Understanding prostate cancer. J R Soc Promot Health 2004;124:219-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Disibio G, French SW. Metastatic patterns of cancers: results from a large autopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:931-9. [PubMed]

- Cummings KB. Nephroureterectomy: rationale in the management of transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. Urol Clin North Am 1980;7:569-78. [PubMed]

- Cohen WM, Freed SZ, Hasson J. Metastatic cancer to the ureter: a review of the literature and case presentations. J Urol 1974;112:188-9. [PubMed]

- Chalasani V, Macek P, O'Neill GF, et al. Ureteric stricture secondary to unusual extension of prostatic adenocarcinoma. Can J Urol 2010;17:5031-4. [PubMed]

- Jallad S, Turo R, Kimuli M, et al. Ureteric stricture: an unusual presentation of metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2012;94:e213-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schneider S, Popp D, Denzinger S, et al. A rare location of metastasis from prostate cancer: hydronephrosis associated with ureteral metastasis. Adv Urol 2012;2012:656023 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang T, Wang Q, Min J, et al. Metastasis to the proximal ureter from prostatic adenocarcinoma: A rare metastatic pattern. Can Urol Assoc J 2014;8:E859-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hongo H, Kosaka T, Yoshimine S, et al. Ureteral metastasis from prostate cancer. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014. [PubMed]

- Huang TB, Yan Y, Liu H, et al. Metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma posing as urothelial carcinoma of the right ureter: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Urol 2014;2014:230852 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Otta RJ, Gordillo C, Fernandez I. Ureteral metastasis of a prostatic adenocarcinoma. Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9:E153-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schallier D, Rappe B, Carprieaux M, et al. Ureteral Metastasis: Uncommon Manifestation in Prostate Cancer. Anticancer Res 2015;35:6317-20. [PubMed]

- Morales I, Bassa C, Pavlovic A, et al. Ureteral Metastasis Secondary to Prostate Cancer: A Case Report. Urol Case Rep 2015;5:4-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary P, Agarwal R, Srinivasan S, et al. Primary adenocarcinoma of ureter: A rare histopathological variant. Urol Ann 2016;8:357-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu P, Liu L, Zu X. Re: Claude Schulman, Erik Cornel, Vsevolod Matveev, et al. Intermittent Versus Continuous Androgen Deprivation Therapy in Patients with Relapsing or Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Phase 3b Randomised Study (ICELAND). Eur Urol 2016;69:720-7. Eur Urol 2017;71:e68 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zollinger RW 2nd, Wise HA 2nd, Clausen KP. An unusual presentation of intrinsic ureteral obstruction secondary to carcinoma of the prostate: a case report. J Urol 1981;125:132-3. [PubMed]

- Singh G, Tiong HY, Kalbit T, et al. Urothelial metastasis in prostate adenocarcinoma. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2009;38:170-1. [PubMed]

- Hulse CA, O'Neill TK. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate metastatic to the ureter with an associated ureteral stone. J Urol 1989;142:1312-3. [PubMed]