Multidisciplinary interview to assess distress in patients waiting for breast cancer treatments

Introduction

In the last decade, screening for distress has been positioned as the sixth vital sign in cancer care, in addition to pulse, respiration, blood pressure, temperature and pain. Distress can be defined as “a multifactor unpleasant emotional experience, along a continuum, ranging from common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears, to problems that become disabling such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation and spiritual crisis” (The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Management Guidelines Panel). As consequence, a correct distress assessment is universally considered a fundamental goal in cancer care, in consideration of the “capacity of distress to interfere with the ability to cope with cancer” (1). Distress is a term with not a specific psycho-pathological meaning and not necessary indicates a formal psychiatric disorder but “it can include even severe mental symptoms and disorders” (2). The international literature shows an important relevance of distress in oncologist patients, about the 30–40% of the population. Italian studies show importance “distress in breast cancer patients developed into the first two years following the diagnosis” (3). Longitudinal studies have shown that, even in successful treatments, distress, including depressive symptoms or disorders, continues “to interfere with normal life months or years after cancer diagnosis” (4). Many studies have been devoted to assessing the “distress associated with the first stage of breast cancer” (5). At all stages, patient self-report instruments or brief assessment with simple verbal inquiry represent the most common methods for the distress evaluation. Because of that, distress scales are usually recommended as first step, and do not permit clinical diagnosis. The most known distress scales are the Thermometer of the Distress (DT) developed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [2003], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale total scale (HADS-T) or Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). The bigger advantage of distress scales seems to be the numeric score that express, in an easy way, the “emotional patient conditions” (6). In many cases, distress scales “are not capable to intercept cases for severe conditions and have not capacity of prediction” (7). It is generally known that distress scales have a high negative predictive value but poor positive predictive value. What motivated our proposal for assessing distress through the Multidisciplinary Interview is the need to have an assessment system that does not take into account, at this first stage, general symptoms such as anxiety or depressed mood. We think that these symptoms, at this phase, are not predictive of the future, because they are too specific, linked to the momentary impact of the disease in life and not quite significant. What is significant, in our proposal, is to understand how women organize these early anxieties and concerns in a communication-narrative that also contains traces of the initial coping. With the term “narrative” of illness is meant the form in which experience is told and experienced with meaning and consistency. The narrative nuclei not only bring the present but also “project into the future by organizing desires and strategies” (8). In other words, the feeling of having a good mastery, a greater locus of control and a feeling of self-efficacy. In this sense, any patient’s personalized request for treatment, not in line with the official guidelines, should be considered and not too quickly attributed to anxiety or other personality traits. Any patient’s request is of utmost importance, and must be, in this initial phase, carefully evaluated. We are interested in distress assessment, in this phase, only in order to distinguish the quote of distress that can be reduced by empowering the decision-making process. As part of the growing personalized care, patient must be considered as one of the key players in the process of making decisions. As is well known, the term “personalized care” for treating breast cancer refers to the review of the most important evidence of systemic and regional conditions and the use of predictive factors. It is immediately apparent that the use of the term personalized care does not include the contribution of the woman to the various therapeutic choices. If the doctor evaluates the possibility, for the woman, to choose from multiple choices, through a medical interview, the various choices are illustrated until they reach a shared therapeutic choice. Often to achieve this shared choice, the contribution of the entire multidisciplinary team and personalized knowledge of the patient is needed through a shared knowledge tool such as the Multidisciplinary Interview, with the contributions of various specialists. More and more frequently, the request to adapt the treatments to personal needs comes from the patient. The requests concern the need for the patient to receive treatments that are less invasive or more radical, such as do not undergo chemotherapy or hormone therapy or ask for a mastectomy instead of a quadrantectomy. The physician’s task becomes to locate the area within which the request can be reasonably taken into account in full respect of their code of ethics. Most screening tests seem to be insufficient to point out the presence of distress factors in the “here and now” and need further follow-up and additional assessments. Our clinical experience with breast cancer patients has shown that some narrative nuclei emerging spontaneously during the first clinical consultation by a psycho-oncologist seem to have an influence over others in determining the development of distress during the cancer trajectory if not treated since the beginning. As a result of this, if it is possible to know, through the narrative of the patients, which themes are more urgent to be treated and more dependent on additional communications, it is possible to intervene immediately throughout interventions capable of reducing future distress. In our hypothesis, it is possible to discriminate between the communication-dependent variables about therapeutic decisions in the here and now from others where it is possible to intervene during the time. The aim of the study is to construct a new distress screening instrument, the Multidisciplinary Interview, which combines, in only one step, a clinical consultation with an instrument at disposal of the whole team in order to intervene on the initial causes of evitable distress.

Methods

Participants

1500 newly diagnosed patients with breast cancer have been involved in the study between 2014 to 2017 at the Multidisciplinary Breast Cancer Unit based at the Catholic University of Rome. Any psychological selection criterion has been applied. The only medical criterion regards the exclusion of metastatic breast cancer patients. The multidisciplinary interview is held in a quiet and comfortable environment, last an hour, and is given by a trained psycho-oncologist of the multidisciplinary team.

Interview description

The Interview collects many different categories of data, including “descriptive-anamnestic data or various emotional conditions that will allow the psycho-oncologist to decide which psychological therapy to offer” (9). In this paper we intend to highlight the nuclei without correlation with other data such as the psychosocial profile and personality characteristics and to concentrate exclusively on free narratives of patients. In fact, we believe that, at this initial level of the first interview, it is crucial to gather the greatest needs expressed without any other conditioning. In fact, the patient is invited to speak spontaneously about her situation a few days after the diagnosis, without suggesting or guiding the interview in any particular direction. This allows the emergence of issues that are more urgent than others in a difficult time such as post-diagnosis for the patient. We find common arguments organized into discourse-narratives that emerge beyond the different narrative, cognitive and emotional styles. What patients talk about when they are invited to do so after receiving a breast cancer diagnosis. The interview is conducted by an experienced psycho-oncologist. It is crucial that the conductor of the interview is an experienced psycho-oncologist. He or she must be capable of listening attentively to what the patient says and able to invite the patient to follow her narration in the direction she prefers. The psycho-oncologist must also pay attention to those “uncertain communications that relate to needs difficult to express or generally unaware” (10). In each interview, all these topics can be presented, of course, at different levels of intensity. It will be the task of the psycho-oncologist to deal with it in subsequent meetings.

Results

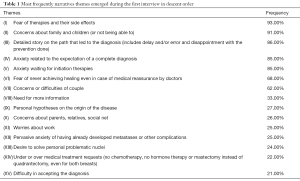

Table 1 reports the narrative themes that have been presented with a frequency greater than 20%. Thematic nuclei are semantic umbrellas under which the most diverse and personal narratives of the disease are grouped in order to categorize and classify the words used by the patients during an interview. Some thematic nuclei are much interconnected (IV and V or II and VII) but we still consider it important to maintain a distinction.

Full table

Conclusions

The tools available for assessing distress are more and more scientifically validated but are excised principally on the individual characteristics of the patient and on the high distress levels that generally characterize the days after the diagnosis. Very often, in the post-diagnosis phase, patients are really confused and afraid and often do not talk to their doctor immediately about their doubts and requests. The distress scales do not take into sufficient account the distress related to being more or less involved in medical decision-making process. The Interview allows to categorize the narrative nuclei that spontaneously emerge during the first interview and to focus on those factors that require the entire team to be informed (Tables 2,3). The risk of physicians not to be informed about the patient’s needs, at this stage, is that the patient gives up or never develops a full compliance. These factors, in our study, mainly concern the involvement of the patient in the various treatment options. Even when there is no medical uncertainty over the prescription, the patient may not accept the prescribed indications because she does not feel sufficiently involved or the option does not meet her needs. In clinical situations where there is uncertainty about choices, the patient is most likely to be involved in the treatment process but not if the request starts from the patient. Moreover, the ever-increasing range of social and cultural changes in cancer imaginary and knowledge and the enormous amount of information that can be easily accessed cannot be ignored. The personalized care should also include the patient’s opinion. As can be seen from the tables, some narrative nuclei such as, for example, the detailed description of the diagnostic pathway, represent the first attempt to cognitively and emotionally organize the shock of the diagnosis. This nucleus is therefore not an element of distress but also the attempt to cope with it through its narration. Likewise, the thematic core of personal hypotheses of illness (theme IX) is an attempt to give shape and meaning to an event that is no longer simply suffered. Some topics concern explicitly psycho-oncological competence (type B) such as family, marital and work difficulties (themes II, VII, and XI) require programming psycho-oncological interventions. Surprisingly, patients do not speak so often how difficult is to accept the diagnosis (theme XV). It is likely that, at this stage, there is a great effort to adapt to the new situation, in almost mechanical form. Other factors of distress (type A) occupy a specific area that requires the intervention of the whole team and such interventions must be timely. Among these elements, a particular position occupies the thematic area of under or over-treatment requests (theme XIV). Very often in the past, these requests were branded as dictated by only anxiety, confusion or ignorance of the patient. It’s difficult to discriminate if the patient has a legitimate request of under or over-treatment or not. That must be evaluated by a specific tool. These demands are constantly increasing nowadays and must become part of the more general process of personalized care. Conversely, welcoming them can mean boosting the patient’s sense of self-management and having a good sense of self-efficacy. These requests, which respond to major social and cultural changes such as the dissemination and disclosure of medical information, can’t be rejected in advance as pathological. Often, behind the rejection of chemotherapy or, more rarely, surgical intervention, it only hides the need for more elaboration and reflection time together with the various team specialists or to share fears and doubts with other women who have had the same experience (support groups). Likewise, behind requests for over-treatment (radical mastectomy even in the absence of medical indication) it hides the adhesion to an interventionist mentality that offers more security in emotional terms. The complexity of such situations and the growing need of women to be protagonists of their therapeutic choices, require increasingly multidisciplinary interventions and collaborative relationships between the members of the care team. As new instrument based on the clinical practice, the Multidisciplinary Interview needs a statistical validation and to correlate the initial factors of distress with medical and biographical data. There is no evidence of reliability. The validation of the Interview will allow having an instrument that applies operative consequences through psychological and medical interventions tailored on the specific needs emerged during the interview to limit and to prevent, as much as possible, future distress during the breast cancer trajectory.

Full table

Full table

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Gianluca Franceschini, Alejandro Martín Sánchez, Riccardo Masetti) for the series “Update of Current Evidences in Breast Cancer Multidisciplinary Management” published in Translational Cancer Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2018.02.17). The series “Update of Current Evidences in Breast Cancer Multidisciplinary Management” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Statement of ethics approval was not required. The research carried out did not involve any variable or additional treatment of the patients. Patients were informed that the interview will be used for research purposes.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Carlson LE, Waller A, Michell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1160-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenglass E. Proactive coping. In: Frydenberg E, editor. Beyond coping: Meeting goals, vision, and challenges. London: Oxford University Press, 2002;37-62.

- Morasso G, Costantini M, Viterbori P, et al. Predicting mood disorders in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:216-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Massie MJ, Holland JC. Depression and cancer patient. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:12-7; discussion 18-9. [PubMed]

- Montgomery M, McCrone SH. Psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase for suspected breast cancer: systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:2372-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Costantini M, Musso M, Viterbori P, et al. Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Support Care Cancer 1999;7:121-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Snowden A, White CA, Christie Z, et al. The clinical utility of the distress thermometer: a review. Br J Nurs 2011;20:220-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Good BJ. Narrare la malattia. Torino: Edizioni di Comunità, 1999.

- Spiegel D. Psychosocial aspects of breast cancer treatment. Semin Oncol 1997;24:S1-36-S1-47.

- Gabbard GO. Psichiatria psicodinamica. Milano: Raffaello Cortina, 1995.