An update in breast cancer management for elderly patients

Introduction

Elderly cancer patients represent a major public health issue. Indeed, the number of elderly patients living with cancer has increased in the last years, due to a longer life expectancy and to the possibility to diagnose cancer early and to treat it accordingly.

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy among women and has the highest incidence in the aging population: it is estimated that 21% of newly diagnosed patients are over 70 years of age. It has been extensively reported that breast cancer-related mortality increases with age, regardless of disease stage (1,2). Overall survival is reduced in patients who are diagnosed when over 55, even when adjusting life expectancy for comorbidities (3,4). These findings can be explained by under-/over-treatment, decreased tolerance to standardized therapy and decreased patient compliance. Optimal treatment of this patient group remains unclear, since elderly patients are often excluded from clinical trials. Despite the importance of the issue, there is little solid evidence regarding the management and treatment protocols for this specific group of patients. Treatment of breast cancer in elderly women in clinical practice is mostly based on randomized clinical trials which have actually excluded these patients from the studied population (5). Furthermore, no specific guidelines were available until 2007, when the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) created the first dedicated task force to provide precise recommendations to treat geriatric breast cancer patients (6). Despite this effort, several issues still remain unsolved. For example, a review on Southwest Oncology Group’s therapeutic trials revealed that in studies about breast cancer, women aged 65 or older constituted only 9% of the enrolled population, despite the fact that 49% of women with breast cancer belongs to this age group (7). Also, patients over 70 made up only 20% of subjects enrolled in US Food and Drug Administration registration trials from 1995 to 1999, although they made up 46% of the US cancer population in that period.

Breast cancer biology changes according to patients’ age but the mechanisms underlying such differences have not yet been understood. Most studies demonstrate that older women are more likely to have hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, low-risk tumor histology disease, with no lymph node involvement, which generally carries a more favorable prognosis. Scientific societies have generally considered cancer in the elderly as less aggressive when compared to younger women and alternative approaches lead to over- or (most likely) under-treat in many cases. However, in the past few years, it has been observed that there has been an increase in more aggressive cancer forms in the geriatric population, and it is estimated that 15–18% of breast cancers in elderly patients is triple negative (8).

Despite the conflicting information regarding the relation between breast cancer biology and aging, in recent years data are accruing that suggest that the intrinsic biological characteristics of the tumor should be used to predict the risk of relapse and guide therapeutic choices. For example, Oncotype DX (Genomic Health) is a 21-gene assay that can predict breast cancer recurrence, chemotherapy efficacy and overall survival. The predictive effect of gene signature was ultimately not age-dependent (9). Similar results were reached using a 70-gene signature test (MammaPrint) in the MINDACT STUDY (10). Even though the results of these studies show that it is reasonable to forgo chemotherapy in women with early breast cancer and favorable tumor biology, it has to be reminded that older women were underrepresented in both studies.

The biological and clinical differences between younger and older patients with breast cancer show that elderly patients should not undergo standard protocols, but should be treated and managed in different ways.

In this article we review the evidence supporting the need for comprehensive geriatric assessment as a guide to treatment choices in older women with breast cancer.

Screening for frailty

Elderly patients are a heterogeneous group due to differences in comorbid conditions, functional capacity and social support, but it is not clear how much each of these aspects is relevant in cancer patients because of under-representation of geriatric population in clinical trials (7). The large variety in characteristics within this population, together with the lack of evidence on the most suitable therapeutic approach and the limited data on older patients’ preferences, make treatment decision-making for these patients generally difficult. Treatment choices for elderly cancer patients should respect the goals of care of the individual patient, and should take into consideration associated conditions and functional capacity. Therefore, all older breast cancer patients should undergo a pre-treatment evaluation, including an assessment of organ function and comorbidity. Such characteristics are important to evaluate the patients’ ability to tolerate treatment (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy) and to guide the oncologist in deciding which treatment is more appropriated. Thus, the aim of the evaluation should be identification of frail or pre-frail patients, that should undergo a more specific geriatric assessment; indeed, it is important to determine which other forms of oncological treatments should be offered, to increase patients’ survival, compliance and treatment tolerance.

Frailty is an extremely common condition in elderly patients. This geriatric syndrome is associated with an increased risk for falls, hospitalization and mortality. For a longtime it has been considered synonymous to disability and comorbidity, while it can be more accurately conceptualized as a distinct entity with protean manifestations, with the concurrent presence of multiple symptoms being necessary for its presentation. Fried et al. (11) proposed the best current working definition of frailty: a clinical syndrome defined by the presence of 3 or more of the following symptoms: (I) unintentional weight loss (4–5 kg in 1 year); (II) self-reported exhaustion; (III) weakness (grip strength <20% in the dominant hand); (IV) slow walking speed (<20% for time to walk 15 feet), and (V) low levels of physical activity (<20% for caloric expenditure). Clinical signs of this condition are represented by undernutrition, sarcopenia, osteopenia and balance and gait disorders. The presence of 2 of the above-mentioned symptoms defines a ‘pre-frail’ process, while the presence of 3 corresponds to the frailty state.

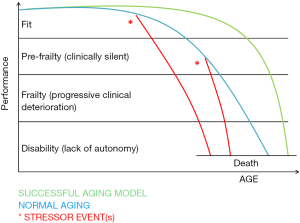

Frailty can be conceptualized as the loss of functional homeostasis, which is the ability of an individual to cope with a stressor without losing function (12). It is an extended process of increasing vulnerability, predisposing to functional decline and ultimately leading to death (13). A continuum exists in the transition from robustness to functional decline. The frailty process is characterized by a loss of physiological reserves, so that the capacity to repair damages to the body is progressively impaired and recovering from illnesses or stressors becomes always more difficult. Many factors contribute to this process, such as age, gender, lifestyle, socioeconomic background, comorbidities and affective, cognitive and/or sensory impairments (14). Three stages in the frailty process can be described: a pre-frail process, the frailty state and frailty complications (15). The dynamics of the frailty process are presented in Figure 1, as modified from (15).

In the pre-frail state physiological reserves are sufficient to allow the organism to respond adequately to an insult (i.e., acute disease, injury or stress) with a chance of complete recovery but also a risk to progress into a frail condition. The frailty state, instead, is characterized by its clinical manifestations and is by no means silent: anorexia, weight loss, generalized weakness (fatigue), gait disorders and fear of falling, causing functional dependence and reduced time spent in outdoor activities, subtle cognitive decline, delirium, and polypharmacy are present (16); yet, if not specifically investigated, these symptoms can be misdiagnosed. The frailty state is characterized by slow and incomplete recovery when exposed to stressors (such as acute diseases or injuries), due to progressive loss of resilience.

Complications of the frailty process are related to this progressive loss of hemostatic reserve, so that capacity of recovery is impossible. The clinical picture is characterized by falls (with consequent fractures and bed rest), progressive functional decline leading to disability, malnutrition polypharmacy, a high-risk of hospitalization, infections, institutionalization and death (17). Cognitive impairment can become more evident, finally leading to overt dementia. As shown in Figure 1, the transition from the pre-frail process (latent phase) to the frail state (clinically apparent) is generally provoked by a trigger event, such as injury, acute disease and/or psychological stress, new drugs and surgery. In particular, for elderly breast cancer patients, the “stress tests” that may unveil frailty are surgery, systemic and/or radio-therapy and the tumor itself. As frailty is a progressive condition that begins with a preclinical stage, there are opportunities for early detection and prevention (18). Frailty differs from ageing and, unlike ageing, it can be prevented and possibly reversed. The identification of frailty in cancer patients is important for oncologists to guide the decision making.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

A comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) has been suggested as a possibly useful approach in dealing with the elderly and frail elderly cancer patients. It is defined as a multidimensional, interdisciplinary diagnostic process focusing on determining an older person’s parameters of function, comorbidity, nutrition, medication, socioeconomic status, and geriatric syndromes. Its aim is to develop a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and long-term follow-up and it can help guide management of reversible comorbidities and geriatric syndromes; also, it is an objective way to assess life expectancy among older adults. Moreover, the CGA allows to identify the deficits that would not be apparent from the history and physical examination alone (19). It is not uncommon in clinical practice to meet elderly patients who do not show overt frailty characteristics (falls, fatigue, polypharmacy or comorbidity), but through the CGA they appear to be in a pre-frail condition, which exposes them to a greater risk of complications and adverse events.

The CGA evaluates in particular: the functional and the psycho-cognitive areas, the socio-economic and the nutritional areas, the presence of polypharmacy, comorbidities, frailty and geriatric syndromes (20-26).

Assessing patients’ functional state is helpful to evaluate the presence of disability as well as identifying those patients at greater risk of developing disability and preventing worsening of their performance indexes. It has been shown that the functional status of the subject is an independent prognostic factor of complications, regardless of oncological or other comorbidities (27,28). Rehabilitation and occupational therapy program, as well as promotion of regular physical activity, could reduce the incidence of disability (29).

Malnutrition is a common condition in the elderly population (30). Analyzing the subject’s nutritional status is critical in preventing many complications such as infections and occurrence of pressure ulcers (31), all conditions that may lead to the extension of the hospitalization period and may affect the prognosis. In addition to Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), serum albumin, Body Mass Index (BMI), and the identification of unintended weight loss can help identify individuals at risk of malnutrition susceptible to dietetic interventions (32).

Evaluation of the cognitive area is also important because mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia can affect the prognosis. The presence of either of these conditions permits to identify those patients who are at greater risk of delirium. Setting up a program of cognitive activity, sleep hygiene, dehydration prevention and the adoption of special measures to improve visual and hearing disorders could be helpful to prevent delirium and cognitive impairment (33).

Depression is a common condition in elderly patients (34) and it causes an increase in mortality and a reduction of the adherence to therapy. It is often atypical and may also be the first non-specific symptom of an associated pathology. By identifying a mood disorder, it is possible to carry out pharmacological therapies and correct a possible cause of cognitive and functional status reduction.

Finally, analyzing the social support of elderly patients is crucial for long-term management. Good social support ensures better treatment adherence and reduced hospitalization (and therefore associated the complications) (35). Patients with low levels of social support can be addressed to the social services, to the appropriate facilities for the continuation of care or to a caregiver, also necessary for the recovery and maintenance of autonomy.

The usefulness of a geriatric assessment is broadly recognized in oncology: the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) (36) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend the incorporation of geriatric assessment in treatment planning (37). Performing CGA in elderly patients with cancer can allow the identification of suspected health conditions, still unrecognized with usual clinical work-up, in order to plan targeted interventions to reverse the problem. CGA also permits prediction of adverse outcomes; a better estimate of residual life expectancy and lethality of the malignancy in the context of competing comorbidities and general health problems. There is strong evidence in the elderly population that increasing administration of CGA to detect potentially reversible conditions (comorbidities, depression, and nutrition) and guide their focused management improves compliance, treatment tolerability, quality of life (QoL), survival (38) and physical function, while decreasing the risk of hospitalization and nursing home placement. CGA has the potential to evaluate the pros and cons of performing or omitting specific oncologic interventions; it identifies geriatric syndromes and age-related problems which cannot be easily detected by routine clinical exams in approximately half of older cancer patients.

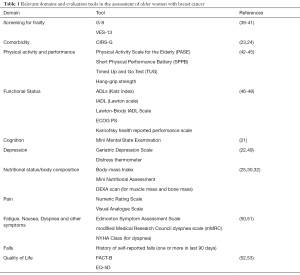

There is currently no standard method for geriatric assessment. Important domains of CGA are functional status, fatigue, comorbidity, cognition, mental health status, social support, nutrition, and geriatric syndromes (e.g., dementia, delirium, falls, incontinence, osteoporosis or spontaneous fractures, neglect or abuse, failure to thrive, constipation, polypharmacy, pressure injuries and sarcopenia). Various tools are available to investigate these domains, and the superiority of one tool over another has not been proven yet. The choice of the instrument might rely on local preference, aim of the tool or available resources. In Table 1 we listed the tools that we propose for the evaluation of elderly patients with breast cancer. The domains covered by the evaluation are based on the International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer (36).

Full table

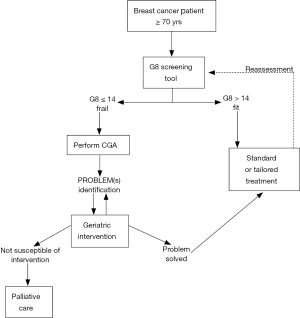

While comprehensive geriatric assessment is the gold standard, it can be time consuming and may not be feasible in a busy oncology practice. As a result, some experts prefer the use of a screening tool (assessment of autonomy, malnutrition, depression, cognition, and comorbidity) to identify vulnerable patients for whom a CGA could potentially optimize cancer treatment. Some of these screening tools include Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13), abbreviated Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (aCGA), Fried Frailty Criteria, Barber Questionnaire (BQ) and the most validated Geriatric8 (G8) (39-41,54). Hurria and colleagues have developed the cancer-specific geriatric assessment (CSGA), that assess cancer patients across seven domains (functional status, comorbidity, polypharmacy, cognitive and nutritional function, psychological status, social support), which is self-administered.

All these screening tools should not replace CGA in evaluation of older cancer patient, because none of these are successful in identifying impairment in all domains of covered by CGA, but they can successfully be used to identify frail patient who would benefit from a CGA before initiating therapy. Among these instruments, G8 has the highest sensitivity; it consists of eight items: a selection of seven items from the MNA questionnaire (food intake, weight loss, body mass index, motor skills, psychological status, number of medications and self-perception of health) and an indication of age in three categories (<80, 80–85, and >85).

A two-step approach has recently been proposed by a geriatric oncology task force to improve the management of older cancer patients (55). The first step is screening all older cancer patients using G8 screening tool. Those patients who result as ‘‘fit’’ at this screening assessment should be considered similar to younger patients and treated accordingly. Instead, patients resulting as frail or “unfit” should require a more in-depth evaluation, the CGA, which is the second step, aimed to design the optimal treatment for this patient group. These patients should not automatically be excluded from the standard oncological treatment because they may still benefit from it but they may need specifically tailored interventions, designed and developed on the basis of the CGA. Because frailty is a transitional state in dynamic progression, it is important to screen breast cancer patients during standard treatment to prevent and, where possible, reverse this process (Figure 2).

QoL in older breast cancer patients

QoL is one of the most important outcome measures in cancer researches due to the medical and public health advances that have determined an interest in measuring quality of treatment not only on the basis of live-spearing and increased life span but also on the basis of QoL in treated patients. It has been shown that assessing QoL in cancer patients could contribute to improve treatment outcomes and could even have a prognostic value (27). The concept of health-related quality of life covers a broad number of aspects that can affect physical and mental health. When assessed on the individual level, health related QoL includes perceptions of physical and mental health, that can be determined by risk factors, health conditions, functional status, social support, and socio-economic status. On a community level, health related QoL includes all factors that can influence health perception and functional capacity, such as use of resources, policies, and practices that have implication for health. Self-assessed health status has been proven a more powerful predictor of mortality and morbidity than many objective measures of health (56): patient-reported QoL has also been found to predict response to treatment (57) and adherence to prescribed therapies, which is especially relevant to older women with early breast cancer who should undergo a long treatment course with aromatase inhibitors (58).

Focusing on HRQoL as an outcome can be useful to allow a more complete and appropriate use of social, mental, and medical services, which is fundamental for a complete management particularly for elderly patients: very few studies have addressed the issue of what happens to this frail population after undergoing treatment.

The gold standard should be that patients self-report their HRQoL. Patient reported outcomes (PROs) is an “umbrella term” that refers to “self-reporting” status by the patient, covering a whole range of potential measurements which are directly reported by the patient without the filter of interpretation by a clinician or anyone else. PRO data ideally should be collected via self-administered questionnaires (59), which the patients fill in themselves. Patient interviews are an acceptable alternative to self-collection (59), however they will only qualify as a PRO, if the interviewer is registering the patient’s point of view without making a professional assessment or judgment of the impact of treatments on the patient’s health status. PRO measures give a picture of the impact of disease as well as treatments on physical and mental health, taken from the patient perspectives, without the intermediation of health workers. They also allow for a direct appraisal of the impact of symptoms and conditions on functional capacity. Measures can be related to absolute or relative changes in signs, symptoms, functions or multidimensional concepts.

The interest in QoL in breast cancer patients is rising because of the increasing number of women with breast cancer, the overall survival rate in cancer patients, and the meaning that breast cancer holds for a woman’s identity. Several valid instruments were used to measure QoL in breast cancer patients, which could be divided into general QoL questionnaires, body-image-related questionnaires, breast-reconstruction-specific questionnaires and chemotherapy specific questionnaires. Among these, FACT-B is a 44-item questionnaire that comprises 5 domains of FACT G [Physical Well-Being, Emotional Well-Being, Social Well-Being (SWB), Functional Well-Being and Relationship with Doctor] in addition to the Breast Cancer Subscale (BCS), which complements the general scale with nine items specific to QoL in breast cancer. In comparison with QLQ-BR23, FACT-B is shorter and covers fewer symptoms and treatment-related side effects, but it allows for a total QoL score, broader coverage of the SWB domain, and the opportunity for patients to provide individualized weighting for the various QoL domains (52).

The assessment of burdening symptoms of disease is essential to the implementation of effective supportive measures (60). The aim of these measures is to offer relief and allowing for better adherence to prescribed treatments and improving quality of life.

Conclusions

Geriatric oncology is an emerging field that is bringing important new notions to the world of oncology. Individualized treatment plans for older women with breast cancer should consider comorbidities, functional status, life expectancy, quality of life, patient’s preferences, and available socioeconomic resources. Increasing representation of older women in clinical trials and incorporating geriatric assessment and multidimensional supportive care are potential ways to improve the outcomes for older patients with breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Gianluca Franceschini, Alejandro Martín Sánchez, Riccardo Masetti) for the series “Update of Current Evidences in Breast Cancer Multidisciplinary Management” published in Translational Cancer Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2018.03.21). The series “Update of Current Evidences in Breast Cancer Multidisciplinary Management” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Markopoulos C, van de Water W. Older patients with breast cancer: is there bias in the treatment they receive? Ther Adv Med Oncol 2012;4:321-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gosain R, Pollock YY, Jain D. Age-related Disparity: Breast Cancer in the Elderly. Curr Oncol Rep 2016;18:69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosso S, Gondos A, Zanetti R, et al. Up-to-date estimates of breast cancer survival for the years 2000-2004 in 11 European countries: The role of screening and a comparison with data from the United States. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:3351-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Li D, et al. Breast cancer among the oldest old: Tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and survival. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2038-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 1999;341:2061-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wildiers H, Kunkler I, Biganzoli L, et al. Management of breast cancer in elderly individuals: recommendations of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:1101-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, et al. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1383-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aapro M, Wildiers H. Triple-negative breast cancer in the older population. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:vi52-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Prospective Validation of a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2005-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardoso F, van't Veer LJ, Bogaerts J, et al. 70-Gene Signature as an Aid to Treatment Decisions in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:717-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fried LP, Tangen C, Walston J. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wells JL, Seabrook J, Stolee P, et al. State of the art in geriatric rehabilitation. Part I: Review of frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:890-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lipsitz LA. Dynamic models for the study of frailty. Mech Ageing Dev 2008;129:675-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rockwood K, Hubbard R. Frailty and the geriatrician. Age Ageing 2004;33:429-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed N, Mandel R, Fain MJ. Frailty: an emerging geriatric syndrome. Am J Med 2007;120:748-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lang PO, Michel JP, Zekry D. Frailty syndrome: A transitional state in a dynamic process. Gerontology 2009;55:539-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fried L, Walston JD. Frailty and Failure to Thrive. In: Hazzard W, Blass JP, Halter JB, et al, Eds. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, 5th Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2003:1487-1502

- Cohen HJ. In search of the underlying mechanisms of frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55:M706-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, et al. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:255-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lazarovici C, Khodabakhshi R, Leignel D, et al. Factors leading oncologists to refer elderly cancer patients for geriatric assessment. J Geriatr Oncol 2011;2:194-9. [Crossref]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull [Internet]. 1988 [cited 2017 Jun 29];24(4):709–11. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3249773

- Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative Illness Rating Scale - Anvita Health Wiki. J Am Geriatr Soc 1968;16:622-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvi F, Miller MD, Grilli A, et al. A manual of guidelines to score the modified Cumulative Illness Rating Scale and its validation in acute hospitalized elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1926-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) for grading the nutritional state of elderly patients: presentation of the MNA, history and validation. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Clin Perform Programme 1999;1:3-11; discussion 11-2. [PubMed]

- Naeim A, Reuben D. Geriatric syndromes and assessment in older cancer patients. Oncology (Williston Park) 2001;15:1567-77,1580; discussion 1581, 1586, 1591.

- Maione P. Pretreatment quality of life and functional status assessment significantly predict survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy: a prognostic analysis of the multicenter Italian lung cancer in the elderly. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6865-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Given B, Given C, Azzouz F, et al. Physical functioning of elderly cancer patients prior to diagnosis and following initial treatment. Nurs Res 2001;50:222-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burhenn PS, Bryant AL, Mustian KM. Exercise promotion in geriatric oncology. Curr Oncol Rep 2016;18:58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Rämsch C, et al. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: A multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1734-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiesser M, Kirchhoff P, Müller MK, et al. The correlation of nutrition risk index, nutrition risk score, and bioimpedance analysis with postoperative complications in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Surgery 2009;145:519-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beck AM, Dent E, Baldwin C. Nutritional intervention as part of functional rehabilitation in older people with reduced functional ability: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J Hum Nutr Diet 2016;29:733-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier P, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med 1999;340:669-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alwhaibi M, Sambamoorthi U, Madhavan S, et al. Cancer type and risk of newly diagnosed depression among elderly medicare beneficiaries with incident breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017;15:46-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silliman RA, Dukes KA, Sullivan LM, et al. Breast cancer care in older women: sources of information, social support, and emotional health outcomes. Cancer 1998;83:706-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2595-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Senior Adult Oncology. 2017. Available online: http://williams.medicine.wisc.edu/senior.pdf

- Pallis AG, Fortpied C, Wedding U, et al. EORTC elderly task force position paper: Approach to the older cancer patient. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:1502-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pélissier S, et al. Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2166-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohile SG, Bylow K, Dale W, et al. A pilot study of the vulnerable elders survey-13 compared with the comprehensive geriatric assessment for identifying disability in older patients with prostate cancer who receive androgen ablation. Cancer 2007;109:802-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luciani A, Ascione G, Bertuzzi C, et al. Detecting disabilities in older patients with cancer: Comparison between comprehensive geriatric assessment and vulnerable elders survey-13. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2046-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:153-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, et al. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 1995;332:556-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:142-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D, et al. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. JAMA 1999;281:558-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963;185:914-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Repetto L, Fratino L, Audisio RA, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: an Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:494-502. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoffman BM, Zevon MA, D’Arrigo MC, et al. Screening for distress in cancer patients: the NCCN rapid-screening measure. Psychooncology 2004;13:792-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991;7:6-9. [PubMed]

- . National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. National clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax 2004;59:1-232.

- Maratia S, Cedillo S, Rejas J. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with breast cancer: a systematic and standardized comparison of available instruments using the EMPRO tool. Qual Life Res 2016;25:2467-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pickard AS, Ray S, Ganguli A, et al. Comparison of FACT- and EQ-5D-based utility scores in cancer. Value Health 2012;15:305-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Overcash JA, Beckstead J, Moody L, et al. The abbreviated comprehensive geriatric assessment (aCGA) for use in the older cancer patient as a prescreen: Scoring and interpretation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2006;59:205-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balducci L, Colloca G, Cesari M, et al. Assessment and treatment of elderly patients with cancer. Surg Oncol 2010;19:117-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mossey JM, Shapiro E. Self-rated health: a predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am J Public Health 1982;72:800-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:557-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro LC, Wheeler SB, Reeder-Hayes KE, et al. Investigating associations between health-related quality of life and endocrine therapy underuse in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract 2017;13:e463-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanatas A, Velikova G, Roe B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in breast oncology: A review of validated outcome instruments. Tumori 2012;98:678-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Naeim A, Aapro M, Subbarao R, et al. Supportive care considerations for older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2627-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]