Oncoplastic breast reconstruction after IORT

Breast-conserving therapy: oncological and aesthetic aspects

Breast-conserving surgery (partial mastectomy) followed by breast irradiation has replaced modified radical mastectomy as the preferred treatment for early-stage invasive breast cancer. The 20-year survival of partial mastectomy with radiation is not statistically different when compared with modified radical mastectomy in patients with Stage I or II breast cancer (1,2). Partial mastectomy includes quadrantectomy (wide excision), segmentectomy (wide local excision) and lumpectomy (local excision). In a study comparing lumpectomy with quadrantectomy, the 5-year incidence of in-breast tumor recurrence was higher in the lumpectomy patients (8, 1%) than in the quadrantectomy patients (3, 1%) (3). The incidence of local recurrence depends upon the tumor margin status, histology subtype, radiation therapy, adjuvant medical treatment, tumor biology, and patient age (4). Most local recurrences occur at the site of initial tumor excision or in the same breast quadrant. In general, during the first ten years after lumpectomy with radiation the recurrence rate is about 1.4% per year. Many studies suggest that local control plays a crucial role in overall survival. The overview of the Early Trialists and Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) approves that differences in local treatment that substantially affect local recurrence rates would avoid about one breast cancer death over the next 15 years for every four local recurrences avoided, and should reduce 15-year overall mortality (5). Therefore the standard treatment for early breast cancer comprises wide local excision, sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection, adjuvant medical treatment and radiotherapy to the whole breast.

A surgical dilemma in breast-conserving treatment arises because, on the one hand, the breast surgeon needs a wider excision to provide clear margin and better local control of disease, but on the other hand, the surgeon wants to spare as much tissue as possible for defect closure and make the resulting aesthetic outcome as favorable as possible. Approximately 10% to 30% of patients are dissatisfied with the aesthetic result after partial mastectomy with radiation (6-8). There are many possible causes of aesthetic failure. Tumor resection can produce distortion, retraction, and noticeable volume changes in the breast. Changes to the position of the nippleareola-complex can extenuate asymmetry. Radiation can also have a profound effect on the breast (edema, skin erythema, hyperpigmentation, fibrosis and retraction).

Breast-conserving surgery: the oncoplastic approach

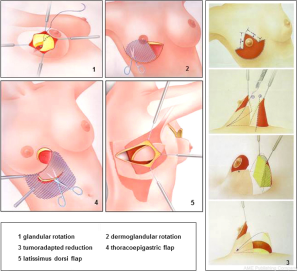

To improve local outcomes and aesthetic results in breast-conserving surgery the combination of a wide local excision with an immediate partial breast reconstruction has been considered a decisive stage in the evolution of breast cancer surgery. This combination, so-called “oncoplastic breast surgery”, allows a wider resection of the tumor with tumor-free resection margins. Moreover, good aesthetic results can be achieved because of the advantage of immediate reconstruction of the partial mastectomy defect (9,10). Numerous surgical techniques with tissue displacement and tissue replacement have been published with different indications, incision lines and suggested rotation techniques, missing a systematic and structured approach for oncoplastic breast surgery (11). During the last years we have defined five reconstruction principles in oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery (12,13). With these five principles we were able to perform more than 95% of all immediate reconstructions of partial mastectomy defects during breast-conserving surgery, resulting in optimized local and aesthetic outcomes. The oncoplastic reconstruction principles of partial mastectomy defects during breast-conserving surgery are as follows: (I) glandular rotation; (II) dermoglandular rotation; (III) tumoradapted reduction mammoplasty; (IV) thoracoepigastric flap; (V) latissimus dorsi flap. To determine which oncoplastic reconstruction principle is best for the individual patient with breast cancer, the size and location of the expected tumor resection, the distance between tumor and overlying skin, and the ratio of breast volume to resection volume must be appreciated.

Breast-conserving therapy: improving local outcome with intraoperative boost radiation

Adjuvant whole-breast radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery greatly reduces the risk for in-breast recurrences and improves overall survival over breast-conserving surgery alone (1,2). Usually the whole breast is irradiated with a dose of 50-56 Gy. An additional dose escalation to the tumor bed as a boost reduces the local relapse rate in selected patients. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) boost-trial reported a local recurrence rate of 4.3% at five years (14). However, there is a considerable risk for geographic miss when the tumor bed boost is provided months after surgery. It has been estimated that the externally delivered boost may partially miss the target volume in approximately 20-90% of cases, especially in oncoplastic tissue displacement techniques. Recently, the concept of intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) as boost during breast-conserving surgery has been introduced using different techniques (15-18). In the Breast Center of the University-Hospital Cologne a mobile IORT device generating low-energy X-rays (50 kV) is used since 2010 for intraoperative boost radiation in non-lobular breast cancer. This IORT-system is applicable to all predefined oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery principles. After oncoplastic wide local excision (segmentectomy) of the tumor, the applicator of the mobile device Intrabeam® (Carl Zeiss Surgical, Oberkochen, Germany) is placed into the tumor bed. Using purse-string sutures the segmentally oriented resection margins of the tumor bed are narrowed to the spherical applicator. To prevent skin toxicity, skin margins were everted before starting IORT. Thereafter, a single dose of 20 Gy is provided at the applicator surface (Figure 1). After complete wound healing and/or chemotherapy whole-breast radiotherapy is initiated. The median treatment time of the boost intraoperatively is 30 minutes. Outpatient treatment is shortened by 1-2 weeks as a result of the omission of the external-beam boost. To date, there have been only a few publications of studies with short-term follow-up in which IORT, provided as a boost, demonstrated the potential to prevent local recurrences in early breast cancer (2.6% at five years) with good to excellent cosmetic results (19). Additional open questions are the lack of the final histopathologic report when IORT is applicated, the uncertainty regarding the definition of the resection margins, and the resected irradiated volume after repeat resection.

Principles and systematics of oncoplastic reconstruction

The interrelationship between breast-tumor ratio, volume loss, cosmetic outcome and margins of clearance is complex, and the widespread popularity of breast-conserving surgery has focused attention on new oncoplastic techniques that can avoid unacceptable cosmetic results. Until now, surgical options have been limited to breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy, the choice depending on fairly well-defined indications and factors. Oncoplastic procedures provide a third option that avoids the need for mastectomy in selected patients and can influence the outcome of breast-conserving surgery in three ways (11).

Oncoplastic procedures allow wide local excisions of breast tissue without risking major local defects and deformity. The use of oncoplastic techniques to prevent deformity can extend the scope of breast-conserving surgery, without compromising the adequacy of resection or the cosmetic outcome. Volume replacement can be used after previous breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy to correct unacceptable deformity and may prevent the need for mastectomy in some cases of local recurrence when further local excision will result in considerable volume loss.

The choice of technique depends on a number of factors, including the extent of resection, location of the tumor, timing of surgery, experience of the breast surgeon in oncoplastic techniques and expectations of the patient. Partial mastectomy reconstruction at the same time as resection is gaining in popularity. As a general rule, it is much easier to prevent than to correct a deformity, as the sequelae of previous surgery do not have to be addressed (20). Immediate reconstruction at the time of partial mastectomy is associated with clear surgical, financial and psychological benefits (21-23).

Resection defects can be reconstructed in one of two ways—(I) by volume displacement with recruiting and transposing local glandular or dermoglandular flaps into the resection site; or (II) by volume replacement, importing volume from elsewhere to replace the amount of tissue resected. Volume replacement techniques can restore the shape and size of the breast, achieving symmetry and excellent cosmetic results without the need for contralateral surgery. However, these techniques require additional operation time and may be complicated by donor-site morbidity, flap loss and an extended reconvalescence. In contrast, volume displacement techniques require less extensive surgery, limiting scars to the breast and avoiding donor-site problems.

Volume displacement techniques

Until recently, little attention has been paid to the cosmetic sequelae of breast-conserving surgery, as most patients are relieved not to lose their breast and many gynaecological and general breast surgeons are unfamiliar with the oncoplastic techniques that can eliminate postoperative deformities. Moreover, there has been a tendency to recommend delayed reconstructive surgery sometime after completion of radiotherapy. Although this is possible, partial reconstruction of the breast after surgery and radiotherapy is technically challenging and requires sophisticated techniques, with cosmetic results that are often disappointing (11).

Poor remodeling is one of the reasons for an ugly deformity after breast-conserving surgery with partial mastectomy (lumpectomy, segmentectomy or quadrantectomy). Although typical localized cancers of small size might be excised well by standard lumpectomy, segmentally extended cancers (invasive breast cancer with DCIS) need more creative approaches to surgical excision to remove breast tumors from nipple to periphery.

This segmentectomy, as our standard procedure in breast-conserving surgery, is a full-thickness segmental resection extending from subdermal (Cooper fascia) to the pectoralis major muscle including the pectoralis fascia. Partial mastectomy defects after segmentectomy can easily be reconstructed using the first standard principle of oncoplastic surgery-the glandular rotation.

Glandular rotation

In cases of segmentectomy without skin resection the glandular defect is easily approximated by mobilising glandular flaps. For the standard segmentectomy a cosmetically placed incision directly over the area to be removed is performed. For lesions especially in the upper breast, incisions are curvilinear following Lange’s lines. The skin is undermined sometimes extensively, liberating the whole quadrant from its skin attachment. In some cases the central portion of the breast needs to be undermined, separating the nipple-areola-complex from the underlying breast tissue. This allows transfer of some of the central volume of the breast towards the defect, making closure easier and preventing deviation of the nipple-areola-complex towards the tumor bed. After clip-marking of the tumor bed, the two lateral glandular flaps are approximated and sutured into the defect. This approach can be used for most breast cancers in almost any location (Figure 2).

Some surgeons perform no remodeling at all, leaving an empty defect and relying on a postoperative haematoma or seroma to fill the space. This may produce acceptable results in the short term but breast retraction invariably occurs with longer follow-up, leading to major deformities that are increased by postoperative radiotherapy (21). On the other hand haematoma or seroma filling leads to a worse inner cosmesis of the breast associated with diagnostic problems in mammography and sonography during follow-up.

Tumor-adapted mastopexy

In oncoplastic resections that include overlying skin because of skin involvement or close relation of the breast cancer to skin less than 5 mm a wide spectrum of individually preferred oncoplastic techniques have been published which can be summarized as tumor-adapted mastopexies. These patients require preoperative planning and patient counselling, and it should not be decided in the operating room that the patient is a candidate for such an approach. The oncoplastic mastopexy techniques include the dermoglandular rotation for tumours in the upper or lower inner quadrant, the “tennis-racket” or Dufour coat technique with NAC recentralisation for location in the upper outer quadrant or the Regnault technique as a modified B-plasty for central, subareolar tumour-localisation.

In our hands we only see clear indications for the principle of dermoglandular rotation for tumors localized in the upper or lower inner quadrant.

Dermoglandular rotation

A limitation of full-thickness excision with the skin of the upper or lower inner breast quadrant is that it can cause upward or downward displacement of the nipple-areola complex, which results when too much skin is removed above or below the nipple. Skin resection is performed in a radial orientation. Grisotti defines the upper inner quadrant as “no man’s land”. A skin resection in this area followed by dermoglandular rotation will sometimes shift the nipple in an upward or medial fashion that would look highly unnatural in location. In such cases, the nipple-areola complex is always displaced towards the reference quadrant and secondary repair of this deformity is difficult. The solution is to prevent this deformity by transferring the nipple-areola complex onto the centre of the new breast dome at the time of primary surgery. Recentralisation of the nipple-areola complex is performed by deepithelialising a periareolar crescent of skin opposite the segmentectomy. The principle of dermoglandular rotation is shown in Figure 1.

Tumor-adapted reduction mammoplasty

Another oncoplastic approach, when breast volume allows it (B cup or larger), is to perform a remodeling mammoplasty. The early use of mammoplasty techniques for breast-conserving surgery involved patients with large tumors located in the lower pole of the breast (superior pedicle mammoplasty). Lower-pole resections cause more deformity than resections in the upper quadrants and these are impossible to prevent with the simple unilateral techniques just described. Some patients develop a major deformity that presents with a characteristic “bird’s peak” appearance, caused by skin retraction on an underfilled lower pole, and downpointing of the nipple. There are many advantages to this approach, but the main disadvantage is the need to achieve contralateral symmetry, which can be performed simultaneously in order to avoid secondary procedures.

There is a large spectrum of published techniques for mammoplasty with limitations in long term aesthetic outcomes, scars and pedicles. We developed a standardized and universal technique with an inferior flap to overcome the limitations of single mammoplasty techniques published before. This principle method can be combined with inverted T-, vertical- and periareolar skin incisions and is applicable for nearly all tumor locations (even the subareolar location) when glandular rotation or dermoglandular rotation is not applicable (Figure 1).

Lateral thoracic wall advancement

For tumours located in the outer upper quadrant the lateral thoracic wall advancement according to Rezai is an oncoplastic alternative to larger resection with dermoglandular rotations like “tennis-racket” or “Dufour-coat” technique.

Volume replacement techniques

Several different approaches to volume replacement have been developed over the last 15 years, including myocutaneous, myosubcutaneous and adipose flaps and implants. Autologous latissimus dorsi flaps are the most popular options because of their versatility and reliability.

The myocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap carries a skin paddle that can be used to replace skin which has been resected at the time of breast-conserving surgery or as a result of contracture and scarring following previous resection and radiotherapy (24-29). Although the skin paddle adds to the replacement volume, it can lead to an ugly “patch” effect because of the differences between the donor skin and the skin of the native breast. A myosubcutaneous latissimus dorsi flap circumvents this problem by harvesting the flap in a plane deep to Scarpa’s fascia, or by deepithelialisation of the flap. This produces a bulky flap without a skin island to reconstruct defects following quadrantectomy, hemimastectomy or skin sparing mastectomy with preservation of the overlying skin.

Volume replacement should always be considered when adequate local tumor excision leads to an unacceptable degree of local deformity in those patients who wish to avoid mastectomy or contralateral surgery. This can occur after loss of 20% or more of the breast volume, particularly when this is resected from the central zone, lower pole or medial quadrants of the breast.

Breast conservation with or without reconstruction should be reserved for patients with unicentric tumors and is inappropriate in those with more widespread disease or T4 tumors. Likewise, latissimus dorsi volume replacement is hazardous in patients with a history suggesting damage to the thoracodorsal pedicle. Patients should be informed that using the latissimus dorsi for breast conservation precludes its subsequent use for full breast reconstruction. If a mastectomy is required to treat recurrent disease, the options are limited to TRAM or perforator flaps.

Donor-site seroma formation occurs in almost all patients, and can be reduced by quilting or delaying drain removal. Flap necrosis is rate, and can be avoided by gentle resection and handling or the pedicle and by taking care to prevent traction injuries during transposition and fixation of the flap after tendon division.

Flap retraction can be avoided by division and fixation of the tendon and careful suture of the flap into the resection defect. Finally, volume replacement can preserve symmetry, and avoids the need for alterations to the contralateral breast in almost all patients.

The role of breast-conserving volume replacement is set to increase as more precise, image-guided resection of specific zones of breast tissue becomes possible. Increasingly sophisticated imaging techniques, such as high-frequency ultrasound and contrast-enhanced dynamic magnetic resonance imaging, may in future enable exact delineation and excision of all malignant and premalignant changes (Figure 1).

Endoscopically assisted techniques may increase the ability to harvest more bulky myosubcutaneous flaps, allowing the reconstruction of more extensive resection defects (30,31). This will require the further development of novel techniques for endoscopic dissection. Today, endoscopically assisted latissimus preparation is not the standard of care.

Thoracoepigastric flap

For patients with breast cancer localized in the upper inner quadrant with a need for a larger skin resection, a small thoracoepigatric flap can be used to reconstruct the resection defect adequately. In most patients a dermoglandular rotation as volume displacement method will be the alternative for the breast-conserving treatment of tumors in this location (Figure 1).

A number of factors need to be considered when making the choice between volume replacement and volume displacement. Volume replacement is particularly suitable for patients who wish to avoid volume loss and contralateral surgery after breast-conserving surgery. They must be prepared to accept a donor-site scar and be made aware of the possibility of major complications that may result in prolonged reconvalescence. Volume replacement is equally well suited to immediate and delayed reconstruction and is the method of choice for correcting severe deformity after previous breast irradiation.

Single center experience (Breast Center, University Hospital of Cologne) with intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) as a boost during oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery

Since 2011 a total of 149 patients were treated with IORT as a boost (20 Gy, Intrabeam®) outside a registered clinical trial during primary oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery, followed by whole-breast radiotherapy (50 Gy in 25 fractions), according to national treatment guidelines.

IORT boost was strictly indicated only in patients with confirmed non-lobular breast cancer without DCIS component in the preoperatively performed core biopsy for diagnosis. After mobilization of glandular tissue the segmental resection borders were narrowed to the IORT-applicator using purse-string sutures (Figure 2). Resection defects were definitely reconstructed after IORT-boost using the predefined oncoplastic reconstruction principles to achieve optimal esthetic results after breast-conserving surgery. To avoid early seroma formation all tumor beds were drained and the drainages were removed when seroma production was less than 10 mL in 24 hours. The median age of the patients was 58 [36-86] years. After histopathological examination of the formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded resection specimens there were pT1 and pT2 tumors in 117 and 29 patients, respectively, and pN0, pN1 and pN2 disease in 111, 26, and 12 patients, respectively. Of the 149 patients, 26 patients had G1 breast cancer, while 96 patients had G2- and 29 patients G3-breast cancer. Evaluation of the tumor biology revealed 127 patients with estradiol receptor positive breast cancer and/or progesterone-receptor-positive breast cancer (luminal A and B subtypes), while only 13 patients had HER2-positive breast cancer. Adjuvant systemic therapies (chemotherapy, HER2 targeting therapy, antihormonal treatment) were indicated according to national and international treatment guidelines. The used IORT-applicator-sizes ranged between 25 and 40 mm in 79% of the patients. The mean radiation time was 21 [18-32] minutes. IORT boost radiotherapy was combined with oncoplastic principles for partial mastectomy reconstruction as follows: glandular rotation (n=109), dermoglandular rotation (n=29), tumoradapted reduction mammoplasty (n=11). Toxicities were prospectively documented using the CTC/EORTC Score 4 weeks after oncoplastic surgery with IORT-boost. Cosmesis was evaluated in patients view after six months using a 1-4 score. Treatment was well tolerated with no grade 3 or 4 acute toxicity. Rare adverse effects following oncoplastic surgery and IORT included wound healing problems (3%), erythema grade I-II (8%), liponecrosis (2%) and seroma formation (12%). The esthetic outcomes were excellent in more than 90% in patients view. During routine follow-up we have not detected local or distant recurrences in the treated patients.

Conclusions

Local outcome and overall survival of breast cancer is depending on tumor biology, tumor burden and therapy strategy. Especially after accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI), local outcome depends on patient selection, age, pathological tumor size, intrinsic subtype and lymph node involvement (32). Today, breast-conserving surgery in combination with whole-breast radiation and external boost radiation is the standard of care for early-stage breast cancer. To further improve the local and aesthetic outcome of breast-conserving surgery, a concept of five oncoplastic principles to reconstruct partial mastectomy defects was developed and introduced in our Breast Center. We demonstrated the applicability of oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery with intraoperative boost radiation (followed by external whole-breast radiation) leading to an optimized local outcome in selected patients. Oncoplastic reconstruction and routine drainage of the tumor bed results in a better aesthetic outcome in breast-conserving therapy in accordance with a low complication rate (e.g., seroma-formation). There are publications for IORT-boost irradiation in combination with lumpectomy during breast-conserving surgery without oncoplastic reconstruction of partial mastectomy defects during breast-conserving therapy, reporting seroma formation rates larger than 20% (33). Long-term follow-up is necessary to evaluate the impact of oncoplastic surgery combined with IORT-boost on the outcome of breast cancer patients according to disease-free and overall survival.

In Germany, a number of gynecologists have subspecialized in oncoplastic breast surgery-following the tradition of gynecology in translational, clinical and surgical research of breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kraemer for corrections of the manuscript and for the scientific implementation of oncoplastic breast surgery at the Breast Center of University of Cologne. Special thanks to Prof. Mallmann, the head of Dept. OB/GYN at the University of Cologne, for his scientific input. Many thanks to Dr. Semrau and Dr. Bongartz of the Dept. Radiotherapy of the University of Cologne for collaboration and IORT performance during surgery.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Frederik Wenz and Elena Sperk) for the series “Intraoperative Radiotherapy” published in Translational Cancer Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2014.01.04). The series “Intraoperative Radiotherapy” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breastconserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1227-32. [PubMed]

- Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1233-41. [PubMed]

- Veronesi U, Volterrani F, Luini A. Quadrantectomy versus lumpectomy for small size breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 1990;26:671-3. [PubMed]

- Haffty BG, Fischer D, Rose M. Prognostic factors for local recurrence in the conservatively treated breast cancer patient: a cautious interpretation of the data. J Clin Oncol 1991;9:997-1003. [PubMed]

- Clarke MEarly Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;366:2087-106. [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Cuminet J, Fitoussi A. Cosmetic sequelae after conservative treatment for breast cancer: classification and results of surgical correction. Ann Plast Surg 1998;41:471-81. [PubMed]

- Rezai M, Veronesi U. Oncoplastic principles in breast surgery. Breast Care 2007;2:277-8.

- Kroll SS, Singletary SE. Repair of partial mastectomy defects. Clin Plast Surg 1998;25:303-10. [PubMed]

- Audretsch W, Rezai M, Kolotas C. Tumor-specific immediate reconstruction in breast cancer patients. Persp Plast Chir 1998;11:71-100.

- Clough KB, Kroll S, Audretsch W. An approach to the repair of partial mastectomy defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:409-20. [PubMed]

- Clough KB, Lewis JS, Couturaud B, et al. Oncoplastic techniques allow extensive resections for breast-conserving therapy of breast carcinomas. Ann Surg 2003;237:26-34. [PubMed]

- Krämer S, Kümmel S, Camara O, et al. Partial mastectomy reconstruction with local and distant tissue flaps. Breast Care 2007;2:299-306.

- Kramer S, Darsow M, Kummel S, et al. Breast-conserving treatment of breast cancer. Gynakol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch 2008;48:56-62. [PubMed]

- Bartelink H, Horiot JC, Poortmans PM, et al. Impact of a higher radiation dose on local control and survival in breast-conserving therapy of early breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized boost versus no boost EORTC 22881-10882 trial. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3259-65. [PubMed]

- Vaidya JS, Tobias JS, Baum M, et al. Intraoperative radiotherapy for breast cancer. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:165-73. [PubMed]

- Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Scheda A, Steil V, et al. Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) for breast cancer using the Intrabeam-System. Tumori 2005;91:339-45. [PubMed]

- Sauer R, Sautter-Bihl ML, Budach W, et al. Accelerated partial breast irradiation. Cancer 2007;110:1187-94. [PubMed]

- Blohmer JU, Kimmig R, Kuemmel S, et al. Intraoperative radiotherapy of breast cancer. Gyn Obstet Rev 2008;48:63-7. [PubMed]

- Blank E, Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Welzel G, et al. Single-center longterm follow-up after intraoperative radiotherapy as a boost during breast-conserving surgery using low kilovoltage x-rays. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:352-8. [PubMed]

- Slavin SA, Love SM, Sadowsky NL. Reconstruction of the irradiated partial mastectomy defect with autogenous tissues. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992;90:854-65. [PubMed]

- Kurtz JM. Impact of radiotherapy on breast cosmesis. Breast 1995;4:163-9.

- Kroll SS, Singletary SE. Repair of partial mastectomy defects. Clin Plast Surg 1998;25:303-10. [PubMed]

- Dean C, Chetty U, Forrest AP. Effect of immediate breast reconstruction on psychosocial morbidity after mastectomy. Lancet 1983;1:459-62. [PubMed]

- Raja MA, Straker VF, Rainsbury RM. Extending the role of breast-conserving surgery by immediate volume replacement. Br J Surg 1997;84:101-5. [PubMed]

- Olivari N. The latissimus flap. Br J Plast Surg 1976;29:126-8. [PubMed]

- Rainsbury RM. Breast-sparing reconstruction with latissimus dorsi miniflaps. Eur J Surg Oncol 2002;28:891-5. [PubMed]

- Dixon JM, Venizelos B, Chan P. Latissimus dorsi mini-flap: a technique for extending breast conservation. Breast 2002;11:58-65. [PubMed]

- Noguchi M, Taniya T, Miyasaki I, et al. Immediate transposition of a latissimus dorsi muscle for correcting a post quadrantectomy breast deformity in Japanese patients. Int Surg 1990;75:166-70. [PubMed]

- Aitken ME, Mustoe TA. Why change a good thing? Revisiting the fleur-de-lis reconstruction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;109:525-33; discussion 534-8. [PubMed]

- Van Buskirk ER, Krehnke RD, Montgomery RL, et al. Endoscopic harvest of the latissimus dorsi muscle using balloon dissection technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;99:899-903; discussion 904-5. [PubMed]

- Fine NA, Orgill DP, Pribaz JJ. Early clinical experience in endoscopic-assisted muscle flap harvest. Ann Plast Surg 1994;33:465-9; discussion 469-72. [PubMed]

- Veronesi U, Orecchia R, Marsonneuve P, et al. Intraoperative radiotherapy versus external radiotherapy for early breast cancer (ELIOT): a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1269-77. [PubMed]

- Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Welzel G, Brade J, et al. Postoperative seroma formation after intraoperative radiotherapy using low-kilovoltage X-rays given during breast-conserving surgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;77:1140-5. [PubMed]