Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in unresectable hepatocellular cancer patients treated with trans-arterial chemoembolization

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancies, and ranks the second of cancer-related mortality globally (1,2), accounting for approximately 598,000 fatalities annually (3). It is the most rapidly increasing cause of cancer mortality, especially in the developing countries (4). Therapeutic options have been standardized by several guidelines. Specifically, for early-stage HCC, liver transplantation and liver resection remain the first option for patients who have the optimal profile, and radiofrequency ablation could be used in the patients with small HCC [single tumor or three tumors <3 cm each, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification stage A] (5). However, due to no obvious early symptoms, up to 60% to 70% of HCC patients are diagnosed with intermediate- to advanced-stage at initial visit (6), most of whom, have no choice to receive potential curative treatment because of advanced tumor stage or deteriorated liver function (7,8). As a result, these patients harbor extremely poor prognosis, with overall survival (OS) ranging from 6 to 20 months (6,9), and a 3-year survival rate of 8–10% (10).

Trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the favorable first-line therapy for intermediate-stage HCC (9) and considered as the standard treatment for unresectable advanced-stage HCC patients by certain international guidelines (11). TACE has been indicated by a meta-analysis to enhance the survival of patients with unresectable HCC, and the beneficial role of TACE in enhancing survival has also been validated by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (9,10).

Nevertheless, from the clinical experience, not all subjects with unresectable HCC could benefit from TACE. Although the status of TACE in HCC therapy has been demonstrated by consensus statements and international guidelines (12-14), relevant guidelines are inconsistent concerning the selection criteria for TACE, and it remains largely undefined of the optimal number of TACE administrations (15). In spite of certain identified prognostic factors for HCC patients, including ascites, physical performance status (PS), tumor size, portal vein thrombosis, extrahepatic spread, vascular invasion, serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) level and various staging systems (10,16-19), these traditional prognostic factors for HCC are limited. For instance, AFP cannot be used to predict the prognosis of HCC patients with normal AFP levels or those with ICC, and other factors should be assessed by imagological examination prior to treatment. In addition, the different complex staging systems are restricted in routine clinical practice. Furthermore, there is no validation of the above factors in unresectable HCC, which results in ineffective survival prediction of subjects with unresectable HCC undergoing TACE. Therefore, it is urgent to explore other predictors, especially serum ones, as criteria for selection tools and for prediction of recurrence as well as survival of HCC patients undergoing TACE.

It is now clear that inflammatory responses are critically involved in multiple stages of tumor development, including tumorigenesis, tumor progression, invasion as well as metastasis (20,21). Malignant cells increase the inflammatory process, which in turn accelerates cancer progression by suppressing apoptosis, promoting angiogenesis as well as DNA damage (22,23). Recent studies have actively probed into the correlation between inflammation-based factors and the prognosis of HCC. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), defined as the ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte count, is considered as a reliable indicator in evaluation of systemic inflammatory variations. NLR reflects the potential balance between neutrophil-associated pro-tumor inflammation and lymphocyte-dependent anti-tumor immune function (20,24-26). That is to say, an increased NLR might stand for enhanced pro-tumor inflammation and declined antitumor immune function.

In addition, the prognostic role of NLR in the post-treatment recurrence and survival of HCC patients undergoing TACE has been widely explored. Nevertheless, the different study designs and sample sizes have yielded to different outcomes. To this end, we conducted a comprehensive review by searching accessible studies in order to investigate the prognostic significance of NLR in HCC patients undergoing TACE.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

We conducted an electronic search of Ovid Medline (1945 to present with daily update; in-process and other non-indexed citations), EMBASE (from 1974 to February 6, 2018), Web of Knowledge including SCIE (Science Citation Index Expanded), and the Cochrane library up to February 2018. Search terms used were as follows: ‘Liver Neoplasm’, ‘Hepatic Neoplasms’, ‘Hepatic Neoplasm’, ‘Cancer of Liver’, ‘Hepatocellular Cancer’, ‘Hepatocellular Cancers’, ‘Hepatic Cancer’, ‘Hepatic Cancers’, ‘Liver Cancer’, ‘Liver Cancers’, ‘Cancer of the Liver’, ‘neutrophil-to lymphocyte ratio’ and ‘NLR’. Hand searching of reference lists of included studies was also undertaken to select relevant studies which were not captured by electronic searching with the final search being undertaken on 6 February 2018.

All citations selected by the search strategy underwent independent assessment by sequentially reviewing title, abstract and full text to establish inclusion or exclusion criteria according to PRISMA guideline. In the cases of unavailable abstract or inadequate abstract details, the full article was reviewed.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible studies were included according to the following criteria: (I) researched HCC patients who underwent TACE; (II) explored the correlation of NLR with OS and/or progression-free survival (PFS)/recurrence-free survival (RFS); (III) researched patients who were not combined with inflammatory disease or infection before treatment of TACE; (IV) researched patients who didn’t have anti-inflammatory treatment before treatment of TACE; and (V) presented in a full paper published in English or in Chinese.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were excluded: (I) duplicates; (II) comments; (III) erratum; (IV) reviews; (V) case reports; (VI) conference presentations (VII) non-clinical studies or experimental studies; (VIII) original studies without evaluation of the prognostic value of NLR in HCC patients undergoing TACE; and (IX) unavailable information from full text to assess quality and to extract data.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) was employed to investigate the quality of retrospective studies (27). To be specific, NOS was composed of three parameters of quality: selection (0–4 points), comparability (0–2 points), and outcome assessment (0–3 points), with a maximal score of 9 points, which represented the highest quality methodological study. Studies with scores ≥7 were defined as high-quality ones.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from the 13 studies: first author, journal, year of publication, type of publication, study design, areas, enrollment period, study population, number of patients, age, gender, tumor stage, therapy type, NLR cut-off values, hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence interval (CI), as well as OS, RFS or PFS according to NLR value. The accuracy of data was confirmed by communicating with the authors and/or journal editors in case of uncertainty.

Results

Selected studies and characteristics

The PRISMA diagram outlining the process of study selection was illustrated in Figure 1. In brief, 348 articles were initially identified, 30 of them underwent detailed review, and 13 eligible studies (28-40) were ultimately enrolled and analyzed according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of the 13 studies, ten were from Eastern countries, including nine from China and one from Japan. The remaining three researches were conducted in Western countries, two and one in the United States and Italy, respectively. Quality evaluation of these studies was shown in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-1.pdf.

The main characteristics of the 13 studies in our review were displayed in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-1.pdf. All articles were retrospective, published after 2011. There were related articles published each year from 2011 to 2018, of which the most published articles were three articles in 2013. The number of patients in each study varied, ranging from 54 to 279, with a total of 1,648 patients, of which 1,578 patients received conventional TACE, 70 patients received DEE. The mean age varied from 49 to 63 years old, and male proportion varied from 65.9% to 92.4%. Ten studies reported the follow up time, which ranged from 6.7 to 15 months. Five studies reported the median OS, ranging from 8.8 to 14.5 months. Three studies reported the median TTP or PFS, which ranged from 5.5 to 7.2 months. Two studies reported the 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS rates, which were 52%, 29%, 20% and 38.8%, 18.5% and 11.1% respectively. One study reported the 88.6%, 46.2%, and 7.5%, respectively. Four studies reported the tumor response information and the objective remission rate (ORR), which ranged from 58% to 87%. HRs were estimated for 10 studies from the accessible information. Twelve studies provided NLR cutoff values, which were determined by diverse approaches among studies, of which six studies reported the median OS difference between high NLR group and low NLR group, which ranged from 4.2 to 11 months and 12 to 17.5 months, respectively.

Study quality

The quality of 13 enrolled researches was shown in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-1.pdf, of which, two and three studies scored 8 and 7 points, respectively. These five papers were rated as high-quality. In addition, there were four studies each with scores of 6 points and 7 points, which were rated as medium-quality.

Prognostic role of pre-TACE NLR in predicting OS of unresectable HCC patients

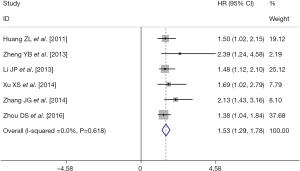

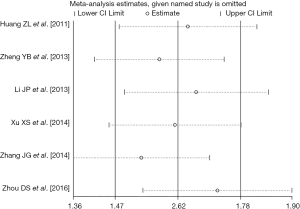

There were six retrospective studies (28,30,32-34,37) reporting data concerning the association of pre-TACE NLR with OS in unresectable HCC patients. A high pre-TACE NLR was likely to be significantly associated with the unfavorable OS in these studies. By using the available HRs and their corresponding 95% CI in these six studies (http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-2.pdf), a meta-analysis was performed. Combined data from the six studies indicated a significant better OS in the high pre-TACE NLR patients group compared to that in the low pre-TACE NLR patients group (pooled HR: 1.53, pooled 95% CI: 1.29–1.78, P<0.001) (Figure 2), without any existing heterogeneity between the included studies in this meta-analysis (I-squared =0.0%, P=0.618) (Figure 2). Sensitivity analyses were subsequently conducted by sequentially omitting each study to investigate its influence on the results, which also indicated that there was no existing heterogeneity, and removing any study did not affect the overall result (Figure 3).

When we carefully reviewed the six studies (28,30,32-34,37) enrolled in the meta-analysis, the following defects of these studies were detected, as shown in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-3.pdf. Firstly, all the included studies were performed in China, without any studies from other countries or ethnicities, leading to reduced generality of the conclusion and its clinical generalizability. Secondly, all the included studies were retrospectively designed with relatively small sample sizes, thereby reducing the statistical power of the data and affecting the convincingness of the conclusion. Thirdly, of all the included studies, the proportion of males exceeded 70%, with many studies reaching as high as about 90%, which may obscure the effect of gender on the conclusion. Fourthly, whether viral hepatitis was combined or not, what kind of viral hepatitis was combined, and what kind of tumor stage it was situated, the above three conditions were different or unknown in each study, whereas, hepatitis and different tumor stages would also have an impact on the relation between pre-TACE NLR and OS. Fifth, the cut-off value of NLR was not uniform, and the method and basis for value selection were various. The research using the ROC method with the most methodological science accounted for a small proportion, which greatly affected the comparability between studies and subsequently influenced the conclusion.

Prognostic role of pre-TACE NLR in predicting PFS/TTP/DFS of unresectable HCC patients

There were three retrospective studies (30,31,33) which provided information regarding the association between pre-TACE NLR and PFS/TTP/DFS of unresectable HCC patients. Detailed clinicopathological information was presented in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-4.pdf. The retrospective study conducted by Zheng YB et al. found that the TTP in the pre-TACE high NLR (NLR ≥4) and low NLR (NLR <4) groups was 4.4 and 7.5 months respectively, which was insignificantly different between the two groups (P=0.28). The retrospective study conducted by McNally ME et al. indicated that PFS was 5.5 months and median TTP in hepatic lesion was 5.6 months, with 76% of patients suffering from progression after one year. In addition, they also demonstrated that elevated pre-TACE NLR (NLR ≥4) was not correlated with PFS in unresectable HCC patients, and the radiographic response to initial TACE was the only clinical factor related to PFS. The retrospective study conducted by Xu XS et al. demonstrated that the DFS at 1, 3, and 5 years for patients with normal NLR were 51.2%, 26.9%, and 26.6% respectively, compared with 29.2%, 18.8%, and 15.6%, respectively for those with elevated NLR. Patients with elevated preoperative NLR harbored significantly worse DFS in comparison to those with normal NLR (DFS, χ2=39.3, P<0.001). However, multivariate analysis indicated that age (P=0.001, HR=1.81; 95% CI: 1.26−2.61) was the only significant prognostic factor in terms of DFS following TACE.

In summary, there is no significant prognostic association of increased NLR before TACE with PFS/TTP/DFS in patients harboring advanced unresectable HCC. These studies (30,31,33) provided research data from both Eastern and Western countries. However, the included studies also had similar defects, such as retrospective research design, small sample size, unbalanced gender ratios, inconsistent tumor stage and cutoff values, as well as confusion in the value standards.

Prognostic role of pre-TACE NLR in predicting TACE treatment-response of unresectable HCC patients

There was only one retrospective study (38) conducted by Taussig MD et al., which provided information regarding the association between pre-TACE NLR and TACE treatment-response of unresectable HCC patients (http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-5.pdf). Objective response was defined as the sum of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR). Disease control was defined as the sum of objective response, PR and stable disease (SD). In their study, through the Kruskal Wallis test, they found that there was a significant association of NLR with disease control (P=0.019) but not with objective response (P=0.225). Multivariate analysis revealed that high NLR (NLR greater than 3) and radioembolization treatment were associated with disease progression. They also performed a frequency distribution of the study population by NLR by performing a stratified contingency analysis. A NLR of >3.1 corresponded to the 4th quartile, which had the most progressive disease and least disease control. Contingency analysis was performed using NLR of >3.1 as a cutoff. Objective response did not demonstrate a difference in control across the quartiles. However, disease control was significantly inferior across quartiles for patients with NLR >3.1 (57%) than for patients with NLR <3 (89%, Fisher’s exact test, P<0.0001), with an odds ratio (OR) of 6.17.

Although their study (38) indicated there was no statistical difference in objective response or disease control by treatment (P=0.088), their research indeed has the problem of inconsistent therapeutic methods for different subjects. Of the 86 patients, 53 (62%) received DEE, 17 (20%) had c-TACE and 16 (19%) had Y90. The same problem also existed in the method and basis for their cutoff value, which was identified based on pooled data in a meta-analysis of NLR in HCC patients treated with surgery, sorafenib, ablation, or chemoembolization, not exclusively for HCC patients treated with chemoembolization. These both affected the universality of the research conclusions. Furthermore, this study also had the similar defects, such as retrospective research design, small sample size, unbalanced gender ratios and undescribed tumor stage. The most important thing was that it was the only one related research.

Prognostic role of post-TACE NLR in predicting post-TACE metastasis of unresectable HCC patients

A retrospective study conducted by Xue TC et al. (36) showed that distant metastasis might occur early following TACE, which was detected in 25.5% (42/165) patients after one to two TACE treatments (http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-6.pdf). The majority of subjects did not present any corresponding symptoms in the case of distant metastasis. Their study found that high post-NLR (NLR ≥5 and NLR ≥6) was significantly correlated with metastasis (P=0.013 and P=0.003), consistent with that of the low post-lymphocyte (P=0.006). Moreover, multivariate analysis further validated that high post-NLR (NLR ≥5 and NLR ≥6) (OR: 1.57, 95% CI: 0.732–3.382, P=0.246) but not high baseline NLR (OR: 2.68, 95% CI: 1.040–6.910, P=0.041) was an independent risk factor in metastatic prediction in consideration of the cross-effects of potential risk indicators.

This study (36) mainly enrolled HCC patients with tumor diameter over 10 cm and harboring hepatitis B and C backgrounds. A further prospective large-scale study is needed to confirm whether the conclusion of this study was equally applicable in patients with a tumor diameter of less than 10 cm and no viral hepatitis background or not.

Prognostic role of post-TACE NLR in predicting TTP and OS of unresectable HCC patients

As shown in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-7.pdf, the retrospective study performed by Zheng YB et al. (30) demonstrated that the median TTP in the high NLR (NLR ≥4) and low NLR (NLR <4) groups was 4.5 and 8.0 months, respectively when 4 to 6 weeks after TACE, without statistical significance (P=0.18). The median OS post-TACE was 7.0 and 16.2 months respectively, with statistical significance (P=0.001). Whereas, another retrospective study performed by Xue TC et al. (36) indicated that the OS was not significantly different between high (NLR ≥5 and NLR ≥6) and low post-NLR groups, as indicated by multivariate analysis (P=0.342).

Among the above-described articles, there was only one (30) concerning the relationship between high NLR and TTP of HCC patients after TACE, and the two studies on high NLR and the OS of HCC patients after TACE were exactly the opposite, which might be due to the inconsistent patient baseline conditions of the two included studies (e.g., tumors greater than 10 cm in diameter and less than 10 cm in diameter). Similarly, these studies also had the same defects, such as retrospective research design, small sample size, unbalanced gender ratios and ununiformed method for identifying cutoff value.

Prognostic role of post-TACE NLR in predicting TACE treatment-response of unresectable HCC patients

Also shown in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-7.pdf, the retrospective study performed by Xue TC et al. (36) failed to detect any statistical significance (P=0.229) of tumor response between high post-NLR (46.15%) and low post-NLR (35.40%) group, although subjects with high post-NLR (46%, 24/52) were prone to suffer from progressive disease compared to those with low NLR (35%, 40/113). Another retrospective study performed by Ying SH et al. (40) found that there was a decreasing trend in NLR of patients in CR group compared to those in non-CR group (P=0.076), however, no correlation of NLR with ORR was found (P=0.873).

Similarly, these two studies (36,40) had the same defects, such as retrospective research design, small sample size, unbalanced gender ratios and ununiformed baseline characteristics of included HCC patients.

Prognostic role of NLR change between pre-and post-TACE in predicting OS of unresectable HCC patients

As shown in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-8.pdf, there were five retrospective studies (28,29,31,32,39) providing information concerning the correlation of the NLR changes between pre- and post-TACE with OS in unresectable HCC patients. A retrospective study conducted by Huang ZL et al. (28) identified 3.3 as the NLR cutoff value according to the mean level of NLR before TACE. They found that better outcomes after TACE in subjects with elevated NLR (n=127) compared to those patients with declined NLR (n=18), which was indicated by 11- and 6-month survival in subjects with elevated and declined NLR, respectively (log-rank test, P=0.006). The survival (14.73±2.0 months) of patients who remained normal after TACE in the normal NLR group was better than that (9.67±0.82 months) of patients who remained high after TACE in the high NLR group (P=0.01). The survival (13.61±1.07 months) of patients who converted to high after TACE in the normal NLR group was better than that (9.67±0.82 months) of patients who remained high after TACE in the high NLR group (P=0.006). In the NLR cutoff value remaining high after TACE in the high NLR group, patients with increased NLR had a better survival than those with decreased NLR (10.19±0.93 vs. 6.63±1.05 months), however, without statistical significance (P=0.128). In the NLR cutoff value remaining normal after TACE in the normal NLR group, patients with increased NLR had a significantly better survival than those with decreased NLR (18.67±2.26 vs. 8.83±2.38 months, P=0.012). Another retrospective study performed by Li JP et al. (32) also reached the same conclusion, the only difference was that their study concluded the survival difference was statistically significant between the NLR-increased patients and NLR-decreased patients in the NLR cutoff value remaining high after TACE in the high NLR group (P=0.034), and they used a much lower NLR cutoff value (2.5). On the contrary to the conclusion of the above two studies (28,32), a retrospective study conducted by Pinato DJ et al. (29) demonstrated that patients with NLR values converted to normal (NLR <5) had a significantly better OS than those with NLR values remaining high or abnormal (NLR ≥5), in addition, post-TACE improvement in the NLR status was related to a less-advanced intrahepatic spread (P=0.02). Moreover, improvement in the NLR (HR: 3.8, 95% CI: 1.1–13.1, P=0.03) remained as an independent indicator for OS, similar to that of the achievement of complete radiologic response (HR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.6, P=0.003) through multivariate analysis. Consistently, the same conclusions were also achieved by a retrospective study conducted by McNally ME et al. (31), who demonstrated that the survival was significantly worse in patients whose NLR was either elevated (>5) 1 month following TACE or was elevated both before and after TACE, in comparison with those with normalized NLR or normal both before and after TACE (18.6 vs. 10.6 months, P=0.026). The consistent findings were detected after six months of TACE (21.3 vs. 9.5 months, P=0.002). Patients harboring abnormal NLR both before and after TACE were burdened with the worst outcomes, with a median survival of 4.1 months. A recent retrospective study performed by Shiozawa S et al. (39) demonstrated three groups of NLR trends: Group A; NLR remained low (≤5)/decreased after TACE, Group B; NLR increased (>5), Group C; NLR remained high both before and after TACE. After TACE treatment, the median survival time (MST) in three groups was as follows: Group A; 46 cases (52.3%), MST 29.4 months, Group B; 27 cases (30.7%), MST 16.6 months, and Group C; 15 cases (17.0%), MST 10.5 months (P=0.008). In the end, high NLR (P=0.006) was an independent factor influencing the survival rate of HCC following TACE, which also supported the conclusion that increased NLR after TACE was related to shorter survival in unresectable HCC patients.

By reviewing the above documents (28,29,31,32,39), whether the increase in NLR after TACE is a favorable or unfavorable factor for unresectable HCC patients remains controversial at present. The former thought that the increase of NLR value is the working-well performance of the patient’s immune system and immune response. The latter thought that the increased NLR value is the performance of the inhibitory immune function of patients, which makes the patients more likely to relapse and metastasis and shorten the survival period in the end. It requires more relevant clinical studies to prove and more basic research to uncover the real mechanism in order to determine which view is ultimately correct. Similarly, these studies also had the same defects, such as retrospective research design, small sample size, unbalanced gender ratios, ununiformed clinical pathology characteristics and ununiformed method for identifying cutoff value.

Prognostic role of NLR change between pre-and post-TACE in predicting TACE treatment-response and PFS of unresectable HCC patients

As shown in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-9.pdf, the retrospective study performed by McNally ME et al. (31) explored the relationship regarding the NLR change between pre-and post-TACE with the TACE treatment-response in unresectable HCC patients. In their study, CR was defined as a complete disappearance or necrosis of all existing tumors. PR was defined as a decline in the size and/or enhancement of all lesions by >50%. SD referred to those, whose disease could not be judged by CR/PR or PD. PD was defined as a >25% increased size of one or more measurable lesions or the appearance of new lesions. Complete radiographic response was noted in 32 patients (36%). PR, SD and PD were detected in 24 (27%), 19 (21%) and 14 (16%) patients, respectively. In their study, they also showed the median TTP was 5.5 months and the median TTP of hepatic lesion was 5.6 months, with 76% of patients suffering from progression at 1 year. Normal NLR cutoff value was defined as <5, which was identified as the previously described. They found that NLR trend (remains normal or normalizes or rises or remains high after TACE) after TACE was not related to either radiographic response to TACE (P=0.89) or hepatic progression (P=0.55).

There only one above study (31) investigating the relationship concerning the NLR change between pre-and post-TACE with the TACE treatment-response of unresectable HCC patients. In this study, most patients (n=59, 56.7%) received standard TACE with triple-drug regimen, while the remaining subjects received either bland embolization or embolization with DEB-TACE, the ununiformed treatment method may affect the universality of the research conclusions. Unfortunately, it also had the same defects, such as retrospective research design, small sample size, unbalanced gender ratios, undefined tumor stage and unscientific identified method for NLR cutoff value for included HCC patients.

Other studies about the prognostic role of NLR in HCC patients treated by TACE

As shown in http://tcr.amegroups.com/public/system/tcr/supp-tcr.2018.07.13-10.pdf, of all the included 13 retrospective studies (28-40), there were two special studies (34,35), which is likely to supply us with novel perspective concerning the prognostic significance of NLR in unresectable HCC patients undergoing TACE and with new research direction in the future. One retrospective study performed by Zhang J et al. (34) found that the presence of PVTT (P<0.001; HR: 4.235; 95% CI: 2.787–6.436), preexisting diabetes mellitus (DM) (P=0.006; HR: 1.843; 95% CI: 1.190–2.854) as well as increased NLR (P<0.001; HR: 2.126; 95% CI: 1.429–3.165) were determined as independent poor prognostic indicators for subjects with non-viral HCC receiving TACE. When pre-existing DM and increased NLR was combined as one single factor, the combination of DM and NLR (P<0.001; HR: 2.235; 95% CI: 1.488–3.357) along with the presence of PVTT (P<0.001; HR: 4.466; 95% CI: 2.924–6.822) were determined as independent factors for poor survival in comparison to that of pre-existing DM or increased NLR alone. On the contrary, another retrospective study conducted by Fan W et al. (35) indicated that the median survival of subjects in the high and low NLR group was 11 (range, 4–24) months and 17 (range, 4–46) months, respectively. The long-term survival was significantly prolonged in subjects with low NLR compared to those with high NLR (log-rank test: P=0.017). Univariate analysis also indicated high NLR (≥3.1, HR: 0.443, 95% CI: 0.276–0.711, P=0.001) could influence OS, while other risk factors, including high PLR, were taken into consideration. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that high PLR (HR: 0.373, 95% CI: 0.216–0.644, P<0.001) but not high NLR was independent predictor of poor survival.

Discussion

Our study systematically reviewed the prognostic significance of NLR in patients with unresectable HCC undergoing TACE. Although there has been a systematic review (41) and three meta-analyses (42-44) examining the relationship between NLR and HCC prognosis, these articles either used the pre-operative NLR as one of the criteria for selecting a liver transplant in patients with HCC (41), either only focusing on the discussion of the prognostic value of NLR in pre-operation period (42,43) or discussing the effect of NLR on the prognosis of different therapeutic periods regardless of distinguishingly different treatments that the HCC patients received (44). To our knowledge, it is the first research which underwent systematical review of the relationship between NLR values at different therapeutic time points and changes in NLR values before and after TACE in patients with unresectable HCC, which has strong pertinence and is of comprehensively clinical significance.

There are several advantages and features of our review that we must acknowledged: (I) a total of 13 articles were included, more comprehensive than the literature included in previous relevant reviews(only four articles included as far as we know); (II) subjects were classified into three groups as pre-TACE NLR, post-TACE NLR, and NLR change pre- and post-TACE in accordance with the diverse therapeutic time points of obtained NLR values; (III) OS, RFS, PFS or DFS and tumor response were chosen as the primary outcomes; (IV) NLR, as an indicator of the inflammatory state and immune function of the body, is very susceptible to confounding factors such as whether the patient has inflammatory disease, whether to receive anti-inflammatory treatment, and whether the immune function is normal. In order to eliminate the effects of these confounding factors, we have developed strict inclusion and exclusion criteria when we included the literature. As indicated by the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the methodology section, studies containing the above confounding factors were excluded. In addition, all included studies have performed multivariate analysis to the baseline data for HCC patients such as gender, age, underlying disease, physical performance, viral hepatitis, and traditional prognostic indicators associated with HCC patient outcomes to exclude or verify the effects of these confounding factors.

In clinical practice, we often use tumor markers, tumor staging and liver function as indicators for evaluating the prognosis of patients with liver cancer. Of the 13 articles (28-40) included, the prognostic value of AFP were evaluated in 12 included articles (28-37,39,40). After multivariate analysis, eight studies (28-31,34-36,40) suggested that AFP had no prognostic value for patients with liver cancer receiving TACE compared with NLR. Two studies concluded that the prognostic value of AFP is higher than that of NLR (33,37). The other 2 studies indicated that the prognostic value of AFP is not as good as that of NLR (32,39). Overall, the prognostic value of NLR is considered to be superior than AFP in majority of the included literatures. What’s more, four studies (29,30,36,40) of the 13 articles (28-31,34-36,40) included in our review evaluated the prognostic value of tumor stage (BCLC grading system) in patients with liver cancer receiving TACE. The multivariate analysis demonstrated that BCLC grading system was not an independent risk factor for patients with liver cancer who were treated with TACE compared with NLR, indicating that NLR is a better prognostic biomarker than tumor stage in patients with HCC received TACE. At last, the Child-Pugh Class or Child-Turcotte Pugh Class system was adapted in all 10 articles (29-31,33-38,40) which evaluated the role of liver function in the prognosis of patients with liver cancer undergoing TACE. Multivariate analysis showed that liver function was not an independent risk factor for prognosis in patients with liver cancer receiving TACE compared with NLR, suggesting that the prognostic value of NLR is much more effective than liver function in patients with HCC underwent TACE. This shows that NLR has a better prognostic power than traditional liver cancer prognostic indicators.

In this study, we mainly demonstrated that high pre-TACE NLR was significantly related to poor OS and high post-TACE NLR was closely related to metastasis. The correlation between high pre-TACE NLR and unfavorable OS was according to a relatively massive related data (six studies including 971 patients for OS). This was consistent with the conclusion of a previous meta-analysis (three articles including 535 patients for OS) (43). However, our analysis included twice as many articles as the latter and more participated patients, hence, the statistical power of our conclusion was stronger than the latter. Therefore, the association between pre-TACE NLR and the OS of HCC subjects undergoing TACE should be stable and could be used to guide the screening of patients in clinical practice. Nevertheless, the three following issues should be pointed out. To begin with, all the included literature regarding on the relationship between pre-TACE NLR with OS of HCC patients came from China and were retrospectively-designed. Therefore, more prospective studies and data from Western countries are necessary to validate our conclusion. Secondly, there was only one study investigating and confirming the correlation between high post-TACE NLR and early metastasis, more relevant studies are warranted to further verify this finding. At last, it is well known that the nutritional status of patients affects the number of neutrophils (45). Although albumin was used to evaluate the nutritional status of patients with liver cancer who underwent TACE in 9 (28,29,32-35,37,39,40) of the 13 articles (28-40) included. Among them, only 4 articles (28,32,33,35) evaluated the relationship between albumin and NLR, all showing that the effect of albumin to NLR was not statistically significant (P>0.05). This is also where the limitations of this study exist, and we need conduct more studies to explore the influence of nutritional status of the body to the lymphocyte or even the NLR in the future.

Another important finding which might inspire us to carry out more relevant research to verify and explore is the role, which high post-TACE NLR and the NLR change trend between pre-and post-TACE played in the OS of HCC patients undergoing TACE. There are only two studies (30,36) investigating the relationship between high post-TACE NLR and OS. One study (30) confirms that high post-TACE NLR is related to poor OS, while another study (36) demonstrates that there is no such relationship. As for the relationship between the trend of NLR and OS, two studies (28,32) suggested that patients with elevated NLR after TACE compared to pre-TACE had a better OS, while three other studies (29,31,39) considered that OS of subjects with elevated NLR after TACE compared to pre-TACE was even worse. The studies that drawn the conclusion of the former thought that the underlying mechanism might follow the development process: firstly, TACE could trigger tumor necrosis and apoptosis by establishing an ischemic microenvironment, and the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents render cancer cells to secrete massive tumor-specific antigens and proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α and type 1 interferons (46); secondly, in turn, the host immune responding to cancer can be activated and accelerated via mobilization of lymphoid and myeloid inflammatory cells into peripheral blood. Particularly, increased level of myeloid neutrophils is secreted into circulation during the acute phase, thereby generating proinflammatory cytokines and chemotactic factors to evoke and recruit various types of granulocytes, including neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, monocytes as well as natural killer (NK) cells (46); thirdly, meanwhile, the migration of circulating lymphocytes into tumor is triggered, leading to a significantly enhanced number of infiltrated lymphocytes in peritumoral stroma, thereby resulting in increased NLR which could be detected in peripheral blood during this period. Exposure to tumor-specific antigens and proinflammatory cytokines could trigger rapid infiltration and activation of antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells and macrophages) and NK cells, with enhanced cytotoxicity of lymphocytes. Ultimately, cancer cells are attacked and damaged by diverse effector mechanisms (47). The studies that came to the conclusion of the latter thought that the underlying mechanism might be related to the following aspects: first, elevated NLR reflects both neutrophilia and relative lymphopenia, both of which are sustained by tumor-secreted cytokines or as part of the immune response of host against neoplastic cells; second, Lymphocyte depletion not only is an adverse prognostic trait (48) but also possibly reflects impaired T-lymphocyte–mediated antitumor response (49) and dysfunctional cytotoxic CD81 lymphocyte subpopulation (50); third, neutrophilia is functionally associated with the systemic secretion of chemokines and ILs, affecting disease progression via promotion of tumor proliferation and angiogenesis (24,51). So, more researches were needed in the future to confirm the role of post-TACE NLR and NLR change trend between pre-and post-TACE in OS of unresectable HCC patients undergoing TACE and explore the real potential underlying mechanism.

The last frustrated finding was that NLR was not correlated with RFS or tumor response in patients with unresectable HCC regardless of obtaining pre-TACE, post-TACE, or changing between pre- and post-TACE. The above-described conditions have limited its application in the formulation of special follow-up and further treatment strategies in unresectable HCC patients after TACE. Other studies (34,35) included in this analysis showed that NLR did not have a predictive effect on the prognosis of HCC patients receiving TACE compared to PLR, whereas, when NLR used in combination with other risk factors for HCC such as diabetes, its ability to predict prognosis was even more potent than NLR alone. The above studies show that the predictive value of NLR in the prognosis of patients with unresectable HCC undergoing TACE is not perfect yet, however, it is of more value in the future to incorporate NLR in predictive models that include other risk factors for the prognosis of HCC.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our review suggests that high pre-TACE NLR is a negative prognostic factor for HCC patients undergoing TACE and it could provide critical data for OS prediction and tumor metastasis in HCC patients undergoing TACE, but NLR is not associated with RFS or tumor response in such patients. Whether elevated NLR after TACE is a protective factor or harmful factor for unresectable HCC patients is still in controversy, and more related studies are necessary to verify its role. Therefore, incorporating NLR in predictive models that include other risk factors for HCC prognosis is a more valuable strategy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by International Science and Technology Cooperation Projects (2015DFA30650 and 2010DFB33720), the Capital Special Research Project for Health Development (2014-2-4012), the Capital Research Project for the Characteristics Clinical Application (Z151100004015170), and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11-0288).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2018.07.13). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bosch FX, Ribes J, Cléries R, et al. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis 2005;9:191-211. v. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87-108. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74-108. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893-917. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruix J, Sherman MAmerican Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Llovet JM, Bruix J. Novel advancements in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma in 2008. J Hepatol 2008;48:S20-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim WR, Gores GJ, Benson JT, et al. Mortality and hospital utilization for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Gastroenterology 2005;129:486-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lencioni R. Loco-regional treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2010;52:762-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology 2003;37:429-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2003;362:1907-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saraswat VA, Pandey G, Shetty S. Treatment algorithms for managing hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2014;4:S80-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kudo M, Izumi N, Kokudo N, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: Consensus-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines proposed by the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) 2010 updated version. Dig Dis 2011;29:339-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raoul JL, Sangro B, Forner A, et al. Evolving strategies for the management of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: available evidence and expert opinion on the use of transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer Treat Rev 2011;37:212-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruix J, Sherman MPractice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2005;42:1208-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cammà C, Schepis F, Orlando A, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology 2002;224:47-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rougier P, Mitry E, Barbare JC, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): an update. Semin Oncol 2007;34:S12-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan CK, Law NM, Ng HS, et al. Simple clinical prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma in developing countries and its validation. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2294-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schöniger-Hekele M, Müller C, Kutilek M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Central Europe: prognostic features and survival. Gut 2001;48:103-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruix J, Llovet JM. Prognostic prediction and treatment strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002;35:519-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010;140:883-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002;420:860-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gunter MJ, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Cross AJ, et al. A prospective study of serum C-reactive protein and colorectal cancer risk in men. Cancer Res 2006;66:2483-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001;357:539-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu Y, Zhao Q, Peng C, et al. Neutrophils promote motility of cancer cells via a hyaluronan-mediated TLR4/PI3K activation loop. J Pathol 2011;225:438-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jablonska J, Leschner S, Westphal K, et al. Neutrophils responsive to endogenous IFN-beta regulate tumor angiogenesis and growth in a mouse tumor model. J Clin Invest 2010;120:1151-64. Erratum in: J Clin Invest 2010;120:4163. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nind AP, Nairn RC, Rolland JM, et al. Lymphocyte anergy in patients with carcinoma. Br J Cancer 1973;28:108-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wells GA, Shea BJ, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analysis. Applied Engineering in Agriculture 2012;18:727-34.

- Huang ZL, Luo J, Chen MS, et al. Blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:702-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pinato DJ, Sharma R. An inflammation-based prognostic index predicts survival advantage after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Res 2012;160:146-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng Y B, Wei Z, Bing L, et al. Prognostic significance of blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing TACE. Chinese Journal of Interventional Imaging & Therapy 2013;10:523-6.

- McNally ME, Martinez A, Khabiri H, et al. Inflammatory markers are associated with outcome in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:923-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li JP, Hu HL, Chen H, et al. Blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. Chinese Journal of Cancer Prevention and Treatment 2013;20:522-5.

- Xu X, Chen W, Zhang L, et al. Prognostic significance of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:4204-9. [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Gong F, Li L, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predict overall survival in non-viral hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Oncol Lett 2014;7:1704-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan W, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios as predictors of survival and metastasis for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after transarterial chemoembolization. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119312 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xue TC, Jia QA, Ge NL, et al. Imbalance in systemic inflammation and immune response following transarterial chemoembolization potentially increases metastatic risk in huge hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2015;36:8797-803. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou D, Liang J, Xu LI, et al. Derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts prognosis for patients with HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma following transarterial chemoembolization. Oncol Lett 2016;11:2987-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taussig MD, Irene Koran ME, Mouli SK, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts disease progression following intra-arterial therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2017;19:458-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shiozawa S, Usui T, Kuhara K, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017;24:A287.

- Ying SH, Zhou J, Gong SL, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio but not ring enhancement could predict treatment response and new lesion occurrence in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma by drug eluting beads transarterial chemoembolization. Transl Cancer Res 2018;7:30-40. [Crossref]

- Saqib R, Pathak S, Smart N, et al. Prognostic significance of pre-operative inflammatory markers in resected gallbladder cancer: a systematic review. ANZ J Surg 2018;88:554-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xue TC, Zhang L, Xie XY, et al. Prognostic significance of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in primary liver cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e96072 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng J, Cai J, Li H, et al. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio as Prognostic Predictors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients with Various Treatments: a Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;44:967-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qi X, Li J, Deng H, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for the prognostic assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget 2016;7:45283-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forse RA, Rompre C, Crosilla P, et al. Reliability of the total lymphocyte count as a parameter of nutrition. Can J Surg 1985;28:216-9. [PubMed]

- Scapini P, Lapinet-Vera JA, Gasperini S, et al. The neutrophil as a cellular source of chemokines. Immunol Rev 2000;177:195-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hicks AM, Riedlinger G, Willingham MC, et al. Transferable anticancer innate immunity in spontaneous regression/complete resistance mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:7753-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ray-Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, et al. Lymphopenia as a prognostic factor for overall survival in advanced carcinomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas. Cancer Res 2009;69:5383-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi N, Hiraoka N, Yamagami W, et al. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells affect the development and progression of hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:902-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang ZQ, Yang ZY, Zhang LD, et al. Increased liver-infiltrating CD8+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are associated with tumor stage in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hum Immunol 2010;71:1180-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuang DM, Zhao Q, Wu Y, et al. Peritumoral neutrophils link inflammatory response to disease progression by fostering angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2011;54:948-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]