Human herpesvirus 6 U94 suppresses tumor cell proliferation and invasion by inhibiting Akt/GSK3β signaling in glioma

Introduction

Glioma is the most common lethal primary brain tumor, with a high recurrence rate, and high morbidity (1). Glioma usually infiltrates into normal brain tissues; therefore, it is difficult to completely eradicate it using common therapeutic strategies, like surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Therefore, other novel therapy methods, such as biological targeting therapy, urgently need to be developed.

HHV-6A and HHV-6B are two variants of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), which is a member of the betaherpesvirus subfamily. Specifically, among herpesviruses, the open reading frame ORF U94/rep is only found in HHV-6A and HHV-6B (2). U94 has strong homology with the adeno-associated parvovirus Rep 78/68 gene, which has an important role in virus integration, replication, and transcription (3). The amino acid identity of U94 to adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep 78/68 gene suggests that there might be some functional similarities between the U94 and Rep 78/68 proteins. U94 is not only a negative regulator of HHV-6 lytic replication, but also has an important effect on the maintenance of viral latency (4,5). Recently, it was shown that HHV-6 U94 possesses DNA-binding, exonuclease, and helicase-ATPase activities, which are required for HHV-6 chromosomal integration (6). Interestingly, several studies showed that U94, as a tumor suppressive gene, has anti-tumor activity. HHV-6 U94 inhibited transformation by the H-ras oncogenic protein and suppressed angiogenesis of blood and lymphatic endothelial cells (7,8). In addition, U94 inhibited the tumorigenesis of prostate cancer by altering fibronectin 1 (FN1) and angiopoietin like 4 (ANGPTL4) gene expression (9). Recently, Caccuri et al. observed that HHV-6 U94 downregulates Src, promotes a partial mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, and inhibits tumor cell growth, invasion, and metastasis in breast cancer (10).

HHV-6 is characterized by an elective tropism for CD4+ T lymphocytes; however, the virus can infect several different cells, including cells of the central nervous system (CNS) (11). Previously, we reported that HHV-6 was detected in glioma tumor tissues (12). However, the roles and underlying mechanisms of U94 in glioma cells are unknown.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the effects of U94 on the progression of glioma. The results suggested that U94 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of glioma cells. Furthermore, U94 significantly suppressed U87 cells tumorigenesis in a nude mouse model. These findings revealed that U94 has a potent tumor suppressor activity in glioma and suggested that U94 might serve as a novel target to treat glioma.

Methods

Cell lines and cell culture

The glioma cell line U87 was purchased from the Type Culture Collection of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen). Cultured cells were maintained in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 ℃.

U94 lentivirus generation and cell infection

The full-length sequence of human herpesvirus 6A U94 (GenBank: MG894374.1:c134129-132657) was synthetized and purchased from GENEWIZ, Inc. (Suzhou, China). GENEWIZ, lnc. then cloned the U94 sequence into plasmid pHAGE-CMV-MCS-IZsGreen-U94 (with a His tag). HEK 293T cells (human embryonic kidney cells) were transfected with pHAGE-CMV-MCS-IZsGreen-U94 (with a His tag) and packaged into plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. At 48 h after transfection, lentiviruses were harvested and used to transduce U87 cells. The expression of U94 was confirmed using an anti-His antibody (Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Danvers, MA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 594 Donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen) using an immunofluorescence assay as described previously (6).

Cell growth and proliferation assay

The cell proliferation was determined using a Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK-8, Dojindo, Japan). Briefly, U94-expressing U87 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2,000 cells per well). After 24, 48 and 72 h, the CCK-8 reagent (10 µL/well) was added into the 96-well plates and incubated for 2 h and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Colony formation assay

The cells were seeded in 35 mm dishes (800 cells/dish) and cultured for 15 days. Colonies were fixed with pre-cooled methanol for 10 min. After washing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the colonies were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 90 sec. For the soft agar colony formation assay, cells were suspended in 0.3% low-temperature melting agar (Sigma-Aldrich) and plated on top of 1.0% solidified agar in 60 mm dishes (5,000 cells/dish). Fifteen days later, the clones were stained with trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich). Colonies that were ≥1 mm in diameter were counted under a microscope.

Wound healing assay

The cells were plated in 6-well plates (104 cells per well). After 24 h, wounds were made in the confluent cell layer by scraping with a 200 µL pipette tip. After washing with PBS three times, the cells were incubated for 12 h. The wound-healing process was monitored under an inverted light microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Transwell migration and invasion assays

The Transwell migration assay was performed as previously reported, with some modifications (13). Briefly, 5,000 cells were suspended in 100 µL of DMEM medium without FBS and seeded into the upper chamber of the 24-well plate (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Then, 600 µL of DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. After incubation for 6 h, the filters were washed with PBS, fixed with pre-cooled methanol for 10 min, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min. A set of images was acquired using NIS Elements image analysis software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell invasion assays were carried out as previously described, with slight modifications (13). The Transwell membrane was covered with 60 µL of Matrigel (100 µg/mL, Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) for 2 h at 37 ℃. Then, 2.5×104 cells in 100 µL of DMEM without FBS were seeded into the upper chamber of the 24-well plate. Then, 600 µL of DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. After incubation at 37 ℃ for 24 h, the invaded cells were fixed with pre-cooled methanol, stained for 30 min with 0.1% crystal violet, and counted under a microscope.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA from U94-expressing and control U87 cells was extracted using the Trizol reagent (Thermo Scientific) and quantified using a NanoDrop ND-2000 apparatus (Thermo Scientific). The cells’ mRNA expression profiles were assessed using PrimeView Human Gene Expression Array (CapitalBio, Beijing, China) as described previously (14). Preprocessing, normalization, and filtering of the CapitalBio data were performed as previously described (14).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

For quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), total RNA was extracted using the Trizol reagent (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated using a RevertAid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). Quantitative PCR was performed using the SYBR Green/ROX Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) in a Step One Plus instrument (Thermo Scientific). The primers used for quantitative PCR were as follows:

Ras-related protein rap-1A (RAP1A) forward: 5'-CGTGAGTACAAGCTAGTGGTCC-3'; RAP1A reverse: 5'-CCAGGATTTCGAGCATACACTG-3'; solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) forward: 5'-TCTCCAAAGGAGGTTACCTGC-3', SLC7A11 reverse: 5′-AGACTCCCCTCAGTAAAGTGAC-3'; forkhead box P1 (FOXP1) forward: 5'-ATGATGCAAGAATCTGGGACTG-3', FOXP1 reverse: 5'-GGATGGCTGAACCGTTACTTTT-3'; transcription factor 4 (TCF4) forward: 5'-CAAGCACTGCCGACTACAATA-3', TCF4 reverse: 5'-CCAGGCTGATTCATCCCACTG-3'; and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) forward: 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3'; GAPDH reverse: 5'-GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA-3'.

All data were normalized to the expression of GAPDH. The relative expression was calculated using the equation, relative quantification (RQ) =2−ΔΔCt (Ct, cycle threshold).

Western blotting

Cell lysates were prepared for western blotting analysis. The antibodies used in these experiments included Anti-SLC7A11 (#12691, CST), anti-TCF4 (#ab217668, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-phospho-AKT (Thr308) (#13038, CST), anti-AKT (#4691, CST), anti-phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) (#5558, CST), and anti-GSK3β (#9315, CST). They were visualized by reaction with HRP-linked second antibody and the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (Pierce, USA). The expression of β-actin (#BS6007M, Bioworld, Shanghai, China) was used as an internal control.

Xenograft tumor experiments

U94-expressing and control U87 cells were inoculated (5×106 cells/spot) into the axilla of athymic nude mice (4 weeks old, female). Mice were weighed, and the tumor width (W) and length (L) were measured using calipers every 6 days. The tumor volume was estimated according to the standard formula: V = 1/2 × L × W2 (15). Twenty-four days after inoculation, the animals were sacrificed and the tumors were extracted. All experimental procedures were performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University under ethical approval number #1701005-1 from Nanjing Medical University.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

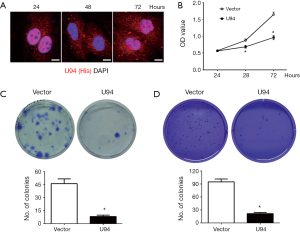

U94 inhibits U87 glioma cell proliferation

U87 cells were transfected with lentiviruses carrying the U94 gene, and the expression of ectopic U94 was confirmed by immunofluorescence. The results showed that ectopic U94 was mainly expressed in nucleus at 24 hours and in cytoplasm at 48 hours, but was expressed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm at 72 hours (Figure 1A). We next determined whether U94 affected the growth of U87 cells. As shown in Figure 1B, elevated U94 expression efficiently inhibited the proliferation of U87 cells at 72 h, as assessed using the CCK-8 assay. Furthermore, the colony formation ability of U94-expressing U87 cells was assessed by colony formation and soft agar colony formation assays. As shown in Figure 1C,D, the numbers and sizes of cell colonies were markedly reduced in U94-expressing U87 cells compared with those of the control cells. These results clearly demonstrated that U94 could inhibit tumor cell growth and colony formation.

U94 inhibits U87 glioma cell migration and invasion

Next, we next explored whether U94 could influence the migration and invasion of tumor cells. Figure 2A shows that U94-expressing U87 cells could inhibit cell migration compared with the control U87 cells using a wound-healing assay. In accordance with the above results, a Transwell migration assay showed that the expression of U94 in U87 cells inhibited cell migration (Figure 2B). In addition, cell invasion ability was evaluated using the Matrigel-based Transwell invasion assay. The results showed that U94 also inhibited the invasion of U87 cells compared with that of the control cells (Figure 2C). These data collectively indicated that ectopic expression of U94 in glioma cells could significantly inhibit cell migration and invasion in vitro.

Ectopic expression of U94 alters gene expression in glioma cells

The gene expression profiles of U94-expressing U87 cells and control U87 cells were investigated by using a microarray. After data analysis, the significantly differentially expressed genes regulated by U94 were identified using unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Figure 3A). The expression levels of RAP1A, SLC7A11, FOXP1, and TCF4 were downregulated in U87-U94 cells compared with those in the control cells. Importantly, the above genes are closely related to the occurrence of malignant tumors (16-19). Then, qRT-PCR was performed to confirm the expression of the above genes. The mRNA levels of RAP1A, SLC7A11, FOXP1, and TCF4 were obviously decreased in U94-expressing U87 cells compared with those in the control group (Figure 3B). Furthermore, western blotting analysis showed that SLC7A11 and TCF4 protein levels were decreased in U94-expressing U87 cells compared with those in the control U87cells (Figure 3C). In addition, the levels of phosphorylated AKT and GSK3β were also reduced in the U94-expressing U87 cells (Figure 3D).

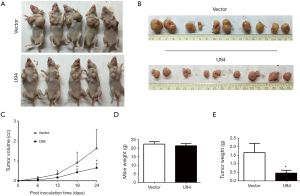

Ectopic expression of U94 inhibits U87 cell tumorigenesis in nude mice

We then constructed tumor xenograft models to determine whether U94 could inhibit tumor growth and tumorigenesis in vivo. U94-expressing U87 cells were subcutaneously injected into both sides of the chest of nude mice. Tumor growth was examined every 6 days. As shown in Figure 4A,B,C, the tumors increased progressively over time in the control mice. However, the growth of the tumors formed from the U94-expressing U87 cells was dramatically inhibited. The average weights of the mice showed no obvious differences between the two groups (Figure 4D). However, the average tumor weights of the U94-expressing U87 cells injection group were much lower than those of the control group (Figure 4E).

Discussion

HHV-6 is a ubiquitous human herpesvirus, which latently infects almost all the adult population. The impact of HHV-6 latent infection on host physiological functions is poorly understood. Similar to symbiotic bacteria, the co-evolution of human viruses suggests that at least herpesvirus could symbiose with human hosts. Herpesvirus latency also brings a benefit to the host. Murine gamma herpesvirus 68 infection protects lupus-prone mice from developing autoimmunity (20,21). In the present study, we focused on HHV-6A U94, a latency-associated gene, and analyzed its effect on the progress of glioma. We demonstrated that U94 inhibited tumor cell growth, colony formation, cell migration, and invasion in U87 glioma cells. Moreover, in vivo experiments showed that ectopic expression of U94 inhibited U87 cells tumorigenesis in nude mice. However, the exact benefit of HHV-6A U94 to the human host requires further investigation.

To further explore the molecular mechanism by which U94 inhibits tumorigenesis in glioma, mRNA microarray and validation experiments were performed. Several target genes were identified, including RAP1A, SLC7A11, FOXP1, and TCF4, which are closely related to the occurrence of malignant tumors (16-19). RAP1A, a member of the Ras family, could activate cascade signaling, such as in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (22). FOXP1, a member of the Fox family of transcriptional repressors, is elevated in primary human hepatocarcinoma cells, colon cancer, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (23,24). SLC7A11 is expressed throughout the brain and facilitates the entry of cysteine into cells in exchange for glutamate (25,26). SLC7A11 expression is elevated in ~50% of human tumors and increased SLC7A11 expression predicted poor survival in patients with malignant glioma (27). TCF4 belongs to the high mobility group DNA binding protein family and is particularly highly expressed in the brain (28). TCF4 activates Wnt signaling, which engages in cross talk with AKT/GSK3β signaling. In the present study, we found that U94 decreased the mRNA levels of RAP1A, SLC7A11, FOXP1, and TCF4 in U87 glioma cells. Additionally, the protein levels of SLC7A11 and TCF4 were also reduced in U94-expressing U87 glioma cells. These findings suggested that AKT/GSK3β signaling might be involved in the anti-tumor effects of U94 on U87 glioma cells. Consistent with the suggested involvement of AKT/GSK3β signaling, the western blotting results showed that U94 could inhibit the phosphorylation of AKT and GSK3β in U87 glioma cells. Although previous research has shown that U94 is a nuclear targeting protein in lymphocytes (5), we found that ectopic U94 was expressed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm in U87 glioma cells. Therefore, we speculated that U94 might be secreted outside the cells and could be taken up by adjacent cells. However, the more detailed mechanism of the anti-tumor activity of U94 in glioma requires further investigation in a future study.

Conclusions

The present study revealed a novel function of HHV-6 U94 in the inhibition of glioma. There are limited effective therapeutic methods to treat glioma; therefore, our results may provide an insight to develop new therapeutic approaches to treat glioma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Lu Chun (Department of Pathogen Biology, Nanjing Medical University) for kindly providing the lentiviral packing system consisting of pHAGE-CMV-MCS-IZsGreen, psPAX2 and pMD2.G.

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 81273235, 81201520, 81571979 and 81301698), the Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation (grant No. Z201409) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant No. BK20171489).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2018.12.17). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All experimental procedures were performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University under ethical approval number #1701005-1 from Nanjing Medical University.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Mehta S, Lo Cascio C. Developmentally regulated signaling pathways in glioma invasion. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018;75:385-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Bolle L, Naesens L, De Clercq E. Update on human herpesvirus 6 biology, clinical features, and therapy. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18:217-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomson BJ, Efstathiou S, Honess RW. Acquisition of the human adeno-associated virus type-2 rep gene by human herpesvirus type-6. Nature 1991;351:78-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rotola A, Ravaioli T, Gonelli A, et al. U94 of human herpesvirus 6 is expressed in latently infected peripheral blood mononuclear cells and blocks viral gene expression in transformed lymphocytes in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:13911-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caselli E, Bracci A, Galvan M, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) U94/REP protein inhibits betaherpesvirus replication. Virology 2006;346:402-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trempe F, Gravel A, Dubuc I, et al. Characterization of human herpesvirus 6A/B U94 as ATPase, helicase, exonuclease and DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:6084-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Araujo JC, Doniger J, Kashanchi F, et al. Human herpesvirus 6A ts suppresses both transformation by H-ras and transcription by the H-ras and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promoters. J Virol 1995;69:4933-40. [PubMed]

- Caruso A, Caselli E, Fiorentini S, et al. U94 of human herpesvirus 6 inhibits in vitro angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:20446-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ifon ET, Pang AL, Johnson W, et al. U94 alters FN1 and ANGPTL4 gene expression and inhibits tumorigenesis of prostate cancer cell line PC3. Cancer Cell Int 2005;5:19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caccuri F, Ronca R, Laimbacher AS, et al. U94 of human herpesvirus 6 down-modulates Src, promotes a partial mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and inhibits tumor cell growth, invasion and metastasis. Oncotarget 2017;8:44533-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yao K, Crawford JR, Komaroff AL, et al. Review part 2: Human herpesvirus-6 in central nervous system diseases. J Med Virol 2010;82:1669-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chi J, Gu B, Zhang C, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 latent infection in patients with glioma. J Infect Dis 2012;206:1394-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang G, Zhang L, Chen X, et al. Formylpeptide Receptors Promote the Migration and Differentiation of Rat Neural Stem Cells. Sci Rep 2016;6:25946. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patterson TA, Lobenhofer EK, Fulmer-Smentek SB, et al. Performance comparison of one-color and two-color platforms within the MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project. Nat Biotechnol 2006;24:1140-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan LX, Wu QN, Zhang Y, et al. Knockdown of miR-21 in human breast cancer cell lines inhibits proliferation, in vitro migration and in vivo tumor growth. Breast Cancer Res 2011;13:R2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reilly JE, Neighbors JD, Hohl RJ. Targeting protein geranylgeranylation slows tumor development in a murine model of prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Biol Ther 2017;18:872-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiang J, Bian C, Wang H, et al. MiR-203 down-regulates Rap1A and suppresses cell proliferation, adhesion and invasion in prostate cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015;34:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang RR, Pointer KB, Kuo JS. Excitotoxic SLC7A11 Expression Is a Marker of Poor Glioblastoma Survival and a Potential Therapeutic Target. Neurosurgery 2015;77:N16-7.

- Song Y, Li X, Zeng Z, et al. Epstein-Barr virus encoded miR-BART11 promotes inflammation-induced carcinogenesis by targeting FOXP1. Oncotarget 2016;7:36783-99. [PubMed]

- Larson JD, Thurman JM, Rubtsov AV, et al. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection protects lupus-prone mice from the development of autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E1092-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barton ES, White DW, Cathelyn JS, et al. Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature 2007;447:326-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hattori M, Minato N. Rap1 GTPase: functions, regulation, and malignancy. J Biochem 2003;134:479-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Datta J, Kutay H, Nasser MW, et al. Methylation mediated silencing of MicroRNA-1 gene and its role in hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2008;68:5049-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams H, Tzankov A, Lugli A, et al. New time-dependent approach to analyse the prognostic significance of immunohistochemical biomarkers in colon cancer and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Pathol 2009;62:986-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T, et al. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J Biol Chem 1999;274:11455-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sato H, Tamba M, Kuriyama-Matsumura K, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of human xCT, the light chain of amino acid transport system xc. Antioxid Redox Signal 2000;2:665-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robert SM, Buckingham SC, Campbell SL, et al. SLC7A11 expression is associated with seizures and predicts poor survival in patients with malignant glioma. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:289ra86 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sepp M, Kannike K, Eesmaa A, et al. Functional diversity of human basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor TCF4 isoforms generated by alternative 5' exon usage and splicing. PLoS One 2011;6:e22138 [Crossref] [PubMed]