Prognosis analysis of lobectomy and sublobar resection in patients ≥75 years old with pathological stage I invasive lung adenocarcinoma of ≤3 cm: a propensity score matching-based analysis

Introduction

Lung cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide and its incidence is still now increasing (1,2). With aging population and development in imaging technology, more and more elderly with early stage lung cancers are being diagnosed than in the past (3). For patients with early-staged non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), surgical resection may provide a potential therapeutic approach (4). As we known, the NCCN guidelines recommend lobectomy combining with mediastinal lymph node dissection as the standard treatment for patients with stage I NSCLC (5). However, for the high-risk patients, sublobectomy is considered to be a compromising solution by many more thoracic surgeons because they can retain more of lung function, especially for the elderly patients with simultaneous multiple primary lung cancer which sublobectomy may preserved a greater possibility for the second primary lung cancer resection (6,7). In addition, sublobectomy may be more appropriate to reduce postoperative morbidity and mortality and prolong the life expectancy in elderly patients. Many observational studies have shown that sublobar resection was comparable to lobectomy in patients with early-stage NSCLC and was more pronounced in older populations (1,8,9). In contrast, a large number of studies have not supported sublobectomy since the only randomized controlled trial (RCT) report in 1995 (10-12). Therefore, it is controversial whether sublobectomy can achieve the same tumor prognosis as lobectomy in elderly patients.

In this study, we utilized the database of the Department of Thoracic Surgery of Shanghai Chest Hospital to investigate the prognosis following sublobectomy versus lobectomy in elderly patients ≥75 years old with stage I lung adenocarcinoma ≤3 cm in size.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital [ID: KS(Y)1668] and limited to patients with age ≥75 and diagnosed with pathological stage I invasive lung adenocarcinoma between 2010 and 2014 in our hospital. Patients who met the following criteria will be excluded: (I) lung cancer was not the first primary malignancy; (II) patients who received radiation therapy prior to surgery; (III) patients did not leave the hospital after surgery or died within 30 days of surgery.

Finally, 255 patients met the inclusion criteria, and the following data for each patient were collected: sex, age at diagnosis, tumor size, tumor location, tumor laterality, pathologic stage, predominant histology subtype, number of lymph nodes examined, surgery resection, lymphatic invasion (LVI), visceral pleural invasion (VPI), adjuvant therapy, relapse-free survival (RFS), lung cancer specific survival (LCSS).

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics between the groups of sublobectomy and lobectomy are compared. Pearson χ2 test was performed for categorical covariates and student’s t-test was performed for continuous ones. Using Kaplan-Meier method to calculate the distribution of RFS and LCSS and the log-rank test was used to probe the significance between these two categories. Univariable and multivariable analyses were performed by a Cox proportional hazards model.

Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to adjust for potential differences in baseline characteristics between patients receiving different surgical procedures. A logistic regression model, including variables of age (treated as a continuous variable), gender, laterality, tumor location, tumor size (treated as a continuous variable) and T stage, was performed to estimate the propensity of undergoing sublobectomy. Then a 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching was established to improve accuracy without a corresponding increase in bias. The matching tolerance value was 0.01.

All the clinicopathologic data and distributions of survival were analyzed by SPSS 23.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) or Prism 5 (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The curves of RFS and LCSS, as well as their comparisons, were calculated by Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. All tests were two-tailed, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 255 patients with median age of 77.3 years were included in this study, 112 underwent sublobectomy and another 143 received lobectomy. The baseline characteristics of our patients before or after PSM were listed in Table 1. There was a significant difference between these two groups in age (P=0.019), tumor size (P=0.007), tumor location (P=0.028), tumor laterality (P=0.010), p-T stage (P=0.006), and the number of harvested lymph node (P<0.001). Baseline bias of preoperative variables was balanced after adjusting for PSM.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Sublobar resection | Lobectomy | P value | Adjusted Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=255) | N=112 | N=143 | − | − |

| Age | 0.019 | 0.140 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 77.69±2.486 | 77.02±2.009 | ||

| Range | 75–85 | 75–83 | ||

| Sex, No. (%) | 0.209 | 0.593 | ||

| Male | 59 (52.7) | 64 (44.8) | ||

| Female | 53 (47.3) | 79 (55.2) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.007 | 0.335 | ||

| ≤1 | 10 (8.9) | 4 (2.8) | ||

| 1–2 | 68 (60.7) | 72 (50.3) | ||

| 2–3 | 34 (30.4) | 67 (46.9) | ||

| Tumor location, No. (%) | 0.028 | 0.118 | ||

| Upper | 78 (69.6) | 87 (60.8) | ||

| Middle | 2 (1.8) | 14 (9.8) | ||

| Lower | 32 (28.6) | 42 (29.4) | ||

| Laterality, No. (%) | 0.010 | 0.645 | ||

| Left | 62 (55.4) | 56 (39.2) | ||

| Right | 50 (44.6) | 87 (60.8) | ||

| p-T stage, No. (%)b | 0.006 | – | ||

| 1a | 10 | 4 | ||

| 1b | 56 | 55 | ||

| 1c | 20 | 49 | ||

| 2a | 26 | 35 | ||

| Predominant histology subtype, No. (%)b | 0.783 | – | ||

| Lepidic | 12 | 12 | ||

| Papillary + acinar | 87 | 109 | ||

| Solid + micropapillary | 9 | 16 | ||

| Variant | 4 | 6 | ||

| Lymph nodes removed, No. (%)b | <0.001 | – | ||

| ≤0 | 101 | 59 | ||

| >5 | 11 | 84 | ||

| VPI, No. (%)b | 0.815 | – | ||

| Yes | 26 | 35 | ||

| No | 86 | 108 | ||

| LVI, No. (%)b | 0.606 | – | ||

| Yes | 4 | 7 | ||

| No | 108 | 136 | ||

| Adjuvant therapy, No. (%)b | 0.868 | – | ||

| Yes | 6 | 7 | ||

| No | 106 | 136 |

a, adjusted for propensity scores; b, these factors were not preoperative characteristics (without adjusted P values), but were included in the Cox analysis for survival. SD, standard deviation.

The average follow-up time was 60.2 months (1.3–99.8 months) before PSM. In our analysis, all of the patient’s death was LCSS, therefore the LCSS in the study is equivalent to the overall survival (OS). Univariable and multivariable analyses for RFS before and after PSM were summarized in Tables 2,3. We identified gender (log-rank P=0.005) and surgical resection (log-rank P=0.002) were all significant prognostic factors for RFS before adjusting, and surgical resection was still a significant prognostic factor after PSM (log-rank P=0.010). Univariable analysis revealed gender (log-rank P=0.029), laterality (log-rank P=0.022) lymph nodes removed (log-rank P=0.043) and surgical resection (log-rank P<0.001) were all significant predictors of LCSS before adjusting while only tumor size (log-rank P=0.012) and surgical resection (log-rank P=0.002) were the significant predictors after PSM (Table 4). Multivariable analysis revealed that tumor size (log-rank P=0.044) and surgical resection (log-rank P=0.002) were still significant prognostic factors for LCSS after PSM (Table 5).

Table 2

| Variable | RFS | RFSa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Age, years | 0.999 (0.880–1.133) | 0.981 | 0.946 (0.798–1.122) | 0.524 | |||

| Sex | 2.301 (1.311–4.040) | 0.004 | 1.417 (0.739–2.716) | 0.294 | |||

| Tumor size | 1.725 (1.032–2.883) | 0.038 | 1.678 (0.914–3.079) | 0.095 | |||

| Tumor location | 0.890 (0.654–1.212) | 0.460 | 0.879 (0.607–1.127) | 0.494 | |||

| Laterality | 0.899 (0.522–1.547) | 0.700 | 0.955 (0.500–1.822) | 0.889 | |||

| T stage | 1.338 (0.974–1.838) | 0.073 | 1.205 (0.834–1.741) | 0.320 | |||

| Predominant histology subtype | 1.407 (0.970–2.042) | 0.072 | 1.718 (1.032–2.861) | 0.037 | |||

| Lymph nodes removed | 0.629 (0.353–1.120) | 0.116 | 0.495 (0.231–1.061) | 0.071 | |||

| Surgical resection | 0.390 (0.217–0.703) | 0.002 | 0.360 (0.177–0.730) | 0.005 | |||

| VPI | 1.422 (0.798–2.536) | 0.232 | 1.149 (0.565–2.338) | 0.701 | |||

| LVI | 1.230 (0.383–3.950) | 0.728 | 1.660 (0.509–5.411) | 0.400 | |||

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.644 (0.157–2.650) | 0.542 | 0.588 (0.141–2.451) | 0.466 | |||

a, these patients included in the Cox analysis for survival were selected using propensity score analysis. RFS, relapse-free survival; VPI, visceral pleural invasion; LVI, lymphatic invasion.

Table 3

| Variable | RFS | RFSa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age, years | 0.934 (0.822–1.062) | 0.299 | 0.940 (0.789–1.120) | 0.491 | |

| Sex | 2.289 (1.276–4.108) | 0.005 | 1.681 (0.811–3.485) | 0.162 | |

| Tumor size | 1.954 (0.695–5.494) | 0.204 | 2.202 (0.612–7.923) | 0.227 | |

| Tumor location | 0.939 (0.678–1.300) | 0.706 | 0.923 (0.615–1.384) | 0.698 | |

| Laterality | 1.003 (0.574–1.752) | 0.992 | 0.934 (0.465–1.876) | 0.848 | |

| T stage | 0.877 (0.260–2.952) | 0.832 | 0.781 (0.179–3.410) | 0.742 | |

| Predominant histology subtype | 1.414 (0.928–2.155) | 0.107 | 1.768 (0.974–3.211) | 0.061 | |

| Lymph nodes removed | 1.053 (0.500–2.216) | 0.892 | 0.910 (0.365–2.272) | 0.840 | |

| Surgical resection | 0.304 (0.143–0.645) | 0.002 | 0.315 (0.131–0.756) | 0.010 | |

| VPI | 1.641 (0.268–10.062) | 0.593 | 1.751 (0.170–17.976) | 0.638 | |

| LVI | 1.103 (0.327–3.716) | 0.875 | 1.842 (0.533–6.364) | 0.334 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.462 (0.104–2.045) | 0.309 | 0.470 (0.101–2.192) | 0.337 | |

a, these patients included in the Cox analysis for survival were selected using propensity score analysis. RFS, relapse-free survival; VPI, visceral pleural invasion; LVI, lymphatic invasion.

Table 4

| Variable | LCSS | LCSSa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age | 0.993 (0.851–1.160) | 0.934 | 0.968 (0.787–1.190) | 0.756 | |

| Sex | 2.062 (1.079–3.942) | 0.029 | 1.146 (0.529–2.484) | 0.729 | |

| Tumor size | 1.590 (0.868–2.914) | 0.134 | 4.686 (1.407–15.599) | 0.012 | |

| Tumor location | 0.870 (0.614–1.233) | 0.433 | 1.010 (0.669–1.527) | 0.961 | |

| Laterality | 0.471 (0.248–0.896) | 0.022 | 0.542 (0.245–1.201) | 0.131 | |

| T stage | 1.319 (0.899–1.936) | 0.156 | 1.052 (0.673–1.643) | 0.824 | |

| Predominant histology subtype | 1.117 (0.706–1.769) | 0.636 | 1.059 (0.505–2.220) | 0.879 | |

| Lymph nodes removed | 0.495 (0.251–0.977) | 0.043 | 0.537 (0.224–1.286) | 0.163 | |

| Surgical resection | 0.260 (0.131–0.515) | <0.001 | 0.277 (0.121–0.635) | 0.002 | |

| VPI | 1.438 (0.736–2.809) | 0.288 | 0.843 (0.351–2.021) | 0.702 | |

| LVI | 0.866 (0.208–3.603) | 0.843 | 0.569 (0.077–4.213) | 0.581 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.536 (0.574–2.785) | 0.306 | 0.042 (0.000–14.594) | 0.289 | |

a, these patients included in the Cox analysis for survival were selected using propensity score analysis. LCSS, lung cancer special survival; VPI, visceral pleural invasion; LVI, lymphatic invasion.

Table 5

| Variable | LCSS | LCSSa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age | 0.936 (0.796–1.100) | 0.421 | 1.013 (0.810–1.267) | 0.912 | |

| Sex | 2.203 (1.108–4.378) | 0.024 | 1.819 (0.777–4.262) | 0.168 | |

| Tumor size | 1.777 (0.545–5.793) | 0.340 | 1.422 (1.182–2.978) | 0.044 | |

| Tumor location | 0.866 (0.593–1.267) | 0.460 | 1.028 (0.647–1.633) | 0.906 | |

| Laterality | 0.511 (0.263–0.992) | 0.047 | 1.267 (0.241–6.664) | 0.780 | |

| T stage | 1.194 (0.285–5.007) | 0.808 | 1.597 (0.239–10.695) | 0.629 | |

| Predominant histology subtype | 1.160 (0.684–1.969) | 0.581 | 1.101 (0.459–2.640) | 0.829 | |

| Lymph nodes removed | 1.037 (0.430–2.505) | 0.935 | 0.891 (0.324–2.447) | 0.823 | |

| Surgical resection | 0.156 (0.063–0.386) | <0.001 | 0.184 (0.063–0.532) | 0.002 | |

| VPI | 1.536 (0.174–13.541) | 0.699 | 0.709 (0.032–15.497) | 0.827 | |

| LVI | 0.816 (0.171–3.892) | 0.798 | 0.690 (0.077–6.179) | 0.740 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.862 (0.287–2.046) | 0.879 | 0.943 (0.810–1.099) | 0.545 | |

a, these patients included in the Cox analysis for survival were selected using propensity score analysis. LCSS, lung cancer special survival; VPI, visceral pleural invasion; LVI, lymphatic invasion.

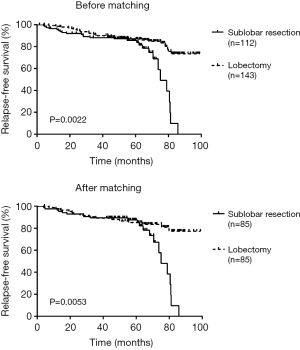

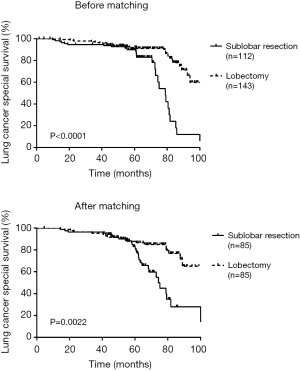

There was a significant difference in RFS and LCSS between sublobectomy versus lobectomy before (RFS log-rank P=0.0022; LCSS log-rank P<0.001) and after (RFS log-rank P=0.0053; LCSS log-rank P=0.0022) adjusting of PSM (Figures 1,2).

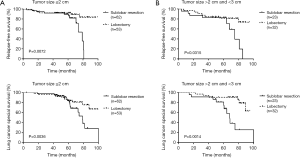

A subgroup analysis of tumor size and the number of harvested lymph nodes was also conducted to further research prognosis between these two groups. Unsurprisingly, we still identify significant difference in RFS or LCSS among those stratified tumor size groups or harvested lymph node groups after PSM (Figures 3,4) except for the RFS in the group of harvested lymph nodes ≤5 (log-rank P=0.0681).

Discussion

For the elderly patients with early-staged lung adenocarcinoma, the debate still persisted over whether sublobectomy could achieve considerable tumor prognosis compared with lobectomy. Razi et al. (13) suggested that sublobectomy should be considered for these specific populations based on the SEER database. De Zoysa et al. (14) also revealed that equivalent survival was observed between sublobectomy and lobectomy for elder patients with stage IA NSCLC and sublobectomy could be considered in high-risk patients. However, another SEER-based analysis showed that patients aged ≥70 years who underwent segmentectomy had significantly worse OS and LCSS than patients who underwent lobectomy, indicating poorer reservation of cardiopulmonary function and a limited life expectancy, thus, limited resections could be recommended for reducing surgery-related morbidity and reserving more pulmonary function (15). Above, it was undefined whether elderly patients with stage I NSCLC were eligible for sublobectomy. In the current study of stage I lung adenocarcinoma with age ≥75 years old, we analyzed the prognosis of patients who underwent sublobectomy and lobectomy, the results showed lobectomy was superior to sublobar resection.

In terms of tumor size, some previous studies have demonstrated equivalent prognosis with sublobectomy for tumor size ≤1 cm, even ≤2 or 3 cm (8,13,16). Varlotto et al. (17) conducted a study of 93 patients with stage I NSCLC who underwent sublobectomy and found tumor size ≥2 cm was a significant indicator for local recurrence. In current study, the RFS and LCSS in elder patient with stage I lung adenocarcinoma was both difference between the two surgical resections in subgroups of tumor size (≤2, >2 and ≤3 cm) after adjusting for propensity scores.

A SEER database analyse of Osarogiagbon and colleagues (18) shown that a continues decline in mortality risk was obtained when the increased number of lymph nodes examined, and the lowest mortality rate was observed when 18–21 lymph nodes were harvested, while the median number of lymph nodes in their study was only 6. In our research, the median number of lymph nodes examined was 2 nodes (0–18 nodes) after PSM, we still identified significant difference in RFS or LCSS among those stratified tumor size groups or harvested lymph node groups after PSM. Conversely, Zhao et al. (19) did not even observe any survival advantages in those patients who underwent lobectomy. Of course, further studies were needed to be done.

There are some limitations of this study. First, many patients had their further therapies in local hospitals and the specific treatments were unknown. Second, we could not further compare the survival difference between lobectomy and wedge resection and segmentectomy because of the relatively small sample size in this study. Third, the shortcoming of our retrospective analysis was unavoidable, hence, the prospective analysis especially randomized clinical trials for sublobectomy and lobectomy for elder patients with stage I lung invasive adenocarcinoma was necessary to be investigated in future.

In summary, this study showed that prognosis of elderly patients (≥75 years) with stage I lung adenocarcinoma ≤3 cm treated with sublobectomy were worse than lobectomy. Lobectomy could be preferable for the treatment of elderly patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. However, prospective randomized trials were still needed to be done for further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2019.03.18). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Informed consent was taken from all patients. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital [ID: KS(Y)1668].

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Altorki NK, Yip R, Hanaoka T, et al. Sublobar resection is equivalent to lobectomy for clinical stage 1A lung cancer in solid nodules. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:754-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2137-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dong S, Du J, Li W, et al. Systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy or mediastinal lymph node sampling in patients with pathological stage I NSCLC: a meta-analysis. World J Surg 2015;39:410-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monirul Islam KM, Shostrom V, Kessinger A, et al. Outcomes following surgical treatment compared to radiation for stage I NSCLC: A SEER database analysis. Lung Cancer 2013;82:90-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim HL, Puymon MR, Qin M, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology™. 2014.

- Kocaturk CI, Gunluoglu MZ, Cansever L, et al. Survival and prognostic factors in surgically resected synchronous multiple primary lung cancers. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;39:160-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zuin A, Andriolo LG, Marulli G, et al. Is lobectomy really more effective than sublobar resection in the surgical treatment of second primary lung cancer? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;44:e120-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kates M, Swanson S, Wisnivesky JP. Survival following lobectomy and limited resection for the treatment of stage I non-small cell lung cancer ≤ 1 cm in size: a review of SEER data. Chest 2011;139:491-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schuchert MJ, Kilic A, Pennathur A, et al. Oncologic outcomes after surgical resection of subcentimeter non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1681-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:615-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kraev A, Rassias D, Vetto J, et al. Wedge resection vs lobectomy: 10-year survival in stage I primary lung cancer. Chest 2007;131:136-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veluswamy RR, Ezer N, Mhango G, et al. Limited resection versus lobectomy for older patients with early-stage lung cancer: impact of histology. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3447. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Razi SS, John MM, Sainathan S, et al. Sublobar resection is equivalent to lobectomy for T1a non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. J Surg Res 2016;200:683-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Zoysa MK, Hamed D, Routledge T, et al. Is limited pulmonary resection equivalent to lobectomy for surgical management of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;14:816-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Yuan C, Zhang Y, et al. Survival following segmentectomy or lobectomy in elderly patients with early-stage lung cancer. Oncotarget 2016;7:19081. [PubMed]

- Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, et al. Effect of tumor size on prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: the role of segmentectomy as a type of lesser resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:87-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Varlotto JM, Medford-Davis LN, Recht A, et al. Identification of stage I non-small cell lung cancer patients at high risk for local recurrence following sublobar resection. Chest 2013;143:1365-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Osarogiagbon RU, Ogbata O, Yu X. Number of lymph nodes associated with maximal reduction of long-term mortality risk in pathologic node-negative non–small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:385-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao ZR, Situ DR, Lau RWH, et al. Comparison of segmentectomy and lobectomy in stage IA adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:890-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]