Axitinib for the first line therapy of renal cancer: failure of a trial or failure of a strategy?

Approximately 64,000 new cases of kidney cancer are estimated to occur in the United States at year 2014 (1). Although most of the cases are localized disease, in which complete surgical resection is a curative option, about 17% of patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis (2). In addition, another 30% of patients diagnosed with localized disease will eventually develop distance recurrence. Patients with disseminated disease will generally succumb of the disease, accounting for the 13,860 deaths projected for this cancer in 2014 (3).

For many years, options of treatment for metastatic disease was restricted to immune stimulating agents, either interferon-alpha or interleukin-2. Both drugs are associated with limiting toxicities and lack of consistent activity and, consequently, are only offered to a restricted cohort of patients (specially in the case of interleukin-2). A more profound understanding of the pathophysiology of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and its dependency of angiogenesis led to the development of new agents. The vast majority of RCC is associated with mutation and/or inactivation of the VHL gene, which cooperates for the degradation of hypoxia-inducible-factor (HIF). When VHL is non-functional, excess of HIF mediates the increase in transcription of a variety of genomic targets, including genes involved in angiogenesis (4). One target of HIF includes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and, consequently, new drugs targeting VEGF pathway became the current basis for treatment of metastatic RCC. Indeed, since 2005 FDA approved four VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (sorafenib, sunitinib, pazopanib and axitinib) and one VEGF-direct antibody (bevacizumab) for the treatment of metastatic RCC.

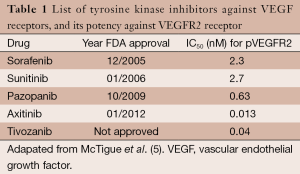

Correlating the year of FDA-approval and the potency for inhibition of VEGFR2 receptors, we can observe that newly approved anti-VEGF TKIs are presenting increased in vitro activity against the principal target of RCC (Table 1). One important raised question in the literature is if these more active drugs will indeed translate into better treatment options for patients. In this context, the study led by Hutson et al. comparing axitinib with sorafenib for the first line treatment of RCC (6) reported important information.

Full table

In summary, Agile 1051 was a phase III trial comparing axitinib with sorafenib in patients with metastatic RCC and no prior systemic therapy. The primary endpoint for this study was progression free survival (PFS), with the aim of detecting a 78% improvement with axitinib. The study showed a median PFS of 10.1 versus 6.5 months for axitinib and sorafenib, respectively. Although PFS was numerically longer with axitinib, this did not reach a pre-specified statistical significance. The study was considered a negative trial and halted the development of axitinib as a first line option for metastatic RCC. In our opinion, the fail of this important study can be discussed either as a consequence of an aggressive proposed primary endpoint or as a demonstration that more potent VEGF inhibition strategy has clinical limitations.

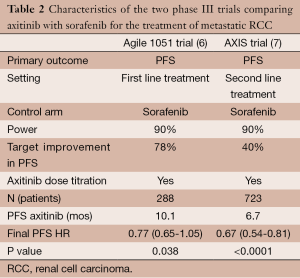

Let’s start with the first hypothesis making some comparisons with the study that led to the FDA-approval of axitinib. The AXIS trial was also a phase III study comparing axitinib with sorafenib, but testing the drugs as a second line therapy for metastatic RCC (7). The study met its primary endpoint of PFS, leading to FDA approval of axitinib. Nonetheless, AXIS trial aimed for a PFS improvement of 40% in the experimental arm, and accrued more than double of patients than the Agile trial (Table 2). Observing the confidence interval (CI) of hazard ratios (HR) between both trials, we can observe that Axis had a more narrowed interval. Consequently, Agile was more ambitious on its objective, but also more underpowered to actually achieve it. TIVO-1 was also another phase III study testing a more potent VEGF receptor TKI, tivozanib, against sorafenib. Although this was not a pure first line trial, 70% of the patients included were treatment-naïve. With 517 patients, TIVO-1 showed a statistical benefit of axitinib over sorafenib in its primary endpoint of PFS (median 11.9 vs. 9.1 months, HR 0.80; 95% CI: 0.64-0.99, P=0.42) (8). The absolute HR was very similar to the Agile trial (HR 0.77), but a narrower CI may indicate a more powerful trial. Hence, it is plausible to consider that if there were a more conservative endpoint and inclusion of more patients, Agile trial would also have been positive for PFS.

Full table

It is important to note that Hutson and colleagues estimated a median PFS between 5.5 and 5.7 months for sorafenib, based on prior trials testing a cytokine refractory and treatment naïve population (9,10). These estimates may not correspond to what has been observed in more recent studies. In a phase II study testing sorafenib as first line treatment, median PFS was 7.5 months (11), while it reached 9 months in a randomized trial that compared single agent sorafenib with the combination of sorafenib and AMG 386 (12). Even in the TIVO-1 study median PFS for sorafenib was 9.1 months. Although we cannot make direct comparisons between trials, this consistent increase in PFS may indicate that the Agile trial initially underestimated the performance of sorafenib as a first line therapy. More importantly, the 6.5 months of PFS found in the sorafenib arm at Agile trial was worst compared to newer studies. Many factors can account for this disparity, including geographic particularities, performance status of patients, or additional supportive treatment. The same factors could also have contributed for an underperformance of the axitinib arm in this trial.

A pre-planned subgroup analysis of the study showed that axitinib prolonged PFS in patients with an Eastern Cooperative Group (ECOG) performance status of zero (13.7 months for axitinib versus 6.6 months for sorafenib, with an unstratified HR of 0.64, 95% CI: 0.42-0.99, P=0.022). Despite the fact that definition of performance status by investigators is subjective and amenable to a series of bias, this subgroup analysis is, at least, hypothesis generating. A randomized study of axitinib with or without dose titration as a first line treatment also demonstrated a difference in PFS according to ECOG performance status (median PFS of 16.6 versus 10.3 months in ECOG 0 and 1 respectively) (13). In light of these findings, it is important to explore the reason for this different performance of axitinib between the groups. Could it be related to an underlying biologic factor? Or maybe the potential ability of an excellent performance status population to tolerate the drug with no dose reductions, or even with more increases in axitinib dose? It would be important for the authors to explore these questions on their next publications of the Agile trial.

Although Agile trial can be considered a negative trial due to its very ambitious statistical design, we can also challenge the strategy of bringing more potent VEGF inhibitors to the clinic. Reviewing the pivotal phase III trials of VEGF blocking agents as first line treatment in metastatic RCC, we can observe that these drugs are reaching a ceiling in terms of PFS. None of them were able to cross the 12 months barrier. On the pivotal trial of sunitinib, median PFS was 11 months (14), while it was 10.2 months with bevacizumab (15), and 9.2 months with pazopanib (16). A more recent comparison of pazopanib and sunitinib, the COMPARZ trial, also showed median PFS of 8.3 and 9.5 months with sunitinib and pazopanib, respectively (17). Newly and more potent VEGF receptor TKIs offered median PFS of 11.9 months (tivozanib in the TIVO-1 trial) and 10.1 (axitinib in the Agile trial). More important, with the availability of second and third line treatments and also the possibility to cross-over from one drug to another, it is hard to believe that differences in overall survival will be observed when more potent VEGF receptor inhibitors are offered as first line options. At last, unfortunately, these new drugs are not less toxic or less expensive, questioning the real benefit that they could offer to the oncology community.

In this setting, it is very questionable if the efforts should be directed to the development of new and more potent VEGF inhibitors. We considerer more plausible to explore alternative targets for the treatment of RCC, including the MET and the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) pathway, along with the exciting field of immunotherapy. These alternatives revealed initial promising results in terms of additive effects upon VEGF inhibition and the possibility of long-term disease control.

Conclusions

In the trial led by Hutson et al., the failure of an increased PFS with axitinib against sorafenib as a first line therapy for metastatic RCC (mRCC) may be explained based on a high statistical bar proposed. Results from another phase III trials evaluating more potent VEGF receptor TKIs, either axitinib in the second line or tivozanib, corroborate this hypothesis. Although axitinib can be considered a more active drug than sorafenib, it is questionable if this drug can offer meaningful clinical benefit for patients as a first line option. As long as the patient is able to receive sequential treatments, it is unlikely that drugs from the same class will prolong definitive outcomes, with offered as a first or second option. At this point, it is plausible to consider that exploration of VEGF as a single target is reaching a limit, and efforts should be directed to agents blocking additional targets and/or immunotherapy for further advances in the treatment of RCC.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Translational Cancer Research for the series “Renal Cell Carcinoma”. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2014.06.10). The series “Renal Cell Carcinoma” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:9-29. [PubMed]

- Kidney and Renal Pelvis [cited 2014 05/17/14]. Available online: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/kidrp.html

- Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1996;335:865-75. [PubMed]

- Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 2009;373:1119-32. [PubMed]

- McTigue M, Murray BW, Chen JH, et al. Molecular conformations, interactions, and properties associated with drug efficiency and clinical performance among VEGFR TK inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:18281-9. [PubMed]

- Hutson TE, Lesovoy V, Al-Shukri S, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1287-94. [PubMed]

- Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;378:1931-9. [PubMed]

- Motzer RJ, Nosov D, Eisen T, et al. Tivozanib versus sorafenib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results from a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3791-9. [PubMed]

- Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:125-34. [PubMed]

- Escudier B, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, et al. Randomized phase II trial of first-line treatment with sorafenib versus interferon Alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1280-9. [PubMed]

- Bellmunt J, Maroto-Rey P, Trigo JM, et al. A phase II trial of first-line sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma unwilling to receive or with early intolerance to immunotherapy: SOGUG Study 06-01. Clin Transl Oncol 2010;12:503-8. [PubMed]

- Rini B, Szczylik C, Tannir NM, et al. AMG 386 in combination with sorafenib in patients with metastatic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Cancer 2012;118:6152-61. [PubMed]

- Rini BI, Melichar B, Ueda T, et al. Axitinib with or without dose titration for first-line metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised double-blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1233-42. [PubMed]

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:115-24. [PubMed]

- Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 2007;370:2103-11. [PubMed]

- Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1061-8. [PubMed]

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:722-31. [PubMed]