Modified subcutaneous suction drainage to prevent incisional surgical site infections after radical colorectal surgery

Introduction

Finding an economical and effective method to reduce SSIs following radical colorectal surgery is important to research. Surgical site infections (SSIs) carries significant morbidity and financial expenses. Many measures have been proven to reduce SSIs; however, the effects have been controversial (1).

The wound infections after radical colorectal surgery are still high, especially in obese patients (2,3). The incidence of wound infections in colorectal surgery has been reported to 20–32% from many randomized controlled trials (4,5). After radical resection of colorectal cancer, the immunity of most patients is low, and the bacteria from the colorectal tract are easy to contaminate the wound and cause incisional SSIs. The presence of liquid and necrotic tissue in the subcutaneous layer is considered to promote the growth of intestinal bacteria, resulting in wound infections (6,7). Therefore, it is believed that clearing contaminated subcutaneous liquid and necrotic tissue can control the incisional SSIs effectively (8). In theory, the placement of a subcutaneous suction drainage tube removing the contaminated subcutaneous liquid and necrotic tissue from the subcutaneous layer in the early postoperative stage before they were infected, is believed to reduce the incisional SSIs (9). There were many RCTs which had studied subcutaneous suction drainage tube to prevent the surgical site incisions. However, some RCTs got positive results, and some got negative results (9,10). The main reason may be that a subcutaneous suction drainage tube is more prone to develop blockages and influences the effect of drainage. In our normal work, we found that intermittent irrigation could effectively prevent drainage tube blockage. Therefore, we evaluated this new method (subcutaneous suction drainage and intermittent irrigation) in patients who underwent radical colorectal surgery.

Methods

Patients

A total of 119 patients who underwent open radical colorectal surgery were included in our study from April 2015 to November 2017. In the beginning, we used the traditional method (suturing the incision directly), and we found that the infection rate of the incision was high. Then we used the new method (subcutaneous suction drainage and intermittent irrigation), and we found that the infection rate of the incision was significantly reduced, so we did a retrospective analysis. There were 58 patients in the control group and 61 patients in the irrigation group. The inclusion criteria are as follows: (I) their subcutaneous fat thickness was more than 1.5 cm by means of CT or MRI measure before operation; (II) the patients had at least one of the following cases before the operation: diabetes mellitus, hypoalbuminemia (ALB ≤35 g/L), anemia (Hb ≤90 g/L), or tumorous obstruction. The exclusion criteria were a history of lower abdominal surgery, emergency operation, secondary operations before the end of primary wound healing, and laparoscopic operation. A retrospective study was performed to evaluate the results of these two groups. The key endpoints were the incidence rate of incisional SSIs, the inpatient stay, and hospitalization expenses.

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Hospital Affiliated to Fujian Medical University, and informed consent was obtained according to institutional regulations. Written informed consent for further clinical research was obtained from participants who used the new method for their clinical records.

Procedure

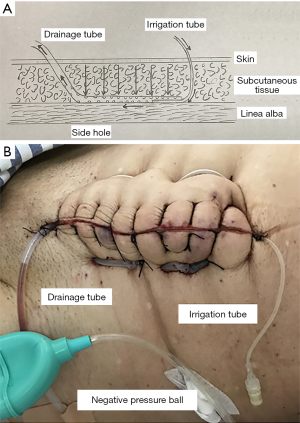

Four surgeons specializing in open radical colorectal surgery participated in our study. The scalpel was used to dissect the skin incision; the subcutaneous fat and linea alba were dissected with an electrical cautery. A drape device was used to protect the wound during the operation. The 1-Vicryl (ETHICON) was used to suture the linea, and the 3-0 MERSILK (ETHICON) was used to suture the skin and subcutaneous fat. 500 mL saline was routinely performed for prophylactic wound irrigation after linea alba closure. Subcutaneous suction drainage and irrigation tubes were inserted in the irrigation group. In these cases, 14- or 16-Fr silicon flexible drains were used for drainage tubes, and on the other side, 8-Fr silicon flexible drains were used for intermittent irrigation tubes. The exit of the tubes was from two sides of the incisions (Figure 1). The drainage tube was connected to a negative pressure ball to allow the whole wound to be drained. On the first day after operation, we opened the irrigation tube. If the air can pass through the drainage tube under the suction of the negative pressure ball, it meant that the two tubes could circulate effectively. Then, we used 20 mL saline to irrigate the drainage under the pressure of the negative pressure ball. If the saline could irrigate the drainage tube effectively, then we used the calcium hypochlorite and boric acid solution (1:1 dilution with saline) to irrigate the drainage tube under the pressure of negative pressure ball again. In the last step, we used the negative pressure ball to suck out the liquid remaining in the drainage tube. The above operation was once or twice a day. Both of the tubes were removed on the third day after the operation, then the port of the drainage tube put a small gauze to drain residual liquid.

Diagnosis of incisional SSIs

The wound was checked by the same senior surgeon every day or two days from the operating day until discharge. After discharge, all patients were followed at the outpatient. Based on the CDC guideline, the diagnosis of incisional infection was as follows: (I) purulent discharge from the incision; (II) positive result of bacteria cultivation from the tissue or liquid which was obtained from the incision aseptically. Incisional SSIs were defined within 30 days after surgery.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The data were presented as a median and variance or as a mean and standard deviation. Differences between continuous variables were analyzed by the Independent-sample t-study. Differences between categorical variables were analyzed by Pearson’s Chi-squared study. P<0.05 was considered to be significant statistically. The incisional surgical site incisions were divided into superficial SSIs and deep SSIs.

Results

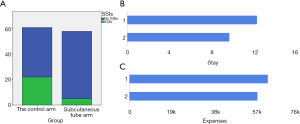

The clinicopathological characteristics of 119 patients are summarized in Table 1. The difference in baseline factors between the groups was not statistically significant. Surgical procedures and outcomes are presented in Table 2. The thickness of subcutaneous fat, wound length, blood loss, and operation time was similar between the groups. One patient with postoperative pulmonary infection in the irrigation group coughed repeated, leading to incision dehiscence. The secondary surgery was performed for this patient. Two patients in the irrigation group had obstruction of the drainage tube, unable to wash. Therefore we removed the irrigation tube and kept the drainage tube. One of these two patients had a local infection of the incision. There were three Incision dehiscences in the control group; all of them accepted the secondary surgery. One of the patients in the control group died of pulmonary infection due to intraoperative aspiration. The incidence of incisional SSIs rate was 27/119 (22.7%) in the overall patients, 22/61 (36.1%) in the control group, and 5/58 (8.6%) in the irrigation group (Figure 2). The rate of SSIs in the irrigation group was significantly lower than the control group (P<0.001). The inpatient stay (9.64±4.15) in the irrigation group was shorter than the control group (12.26±5.55) (P=0.004) (Figure 2). The hospitalization expenses (57,356±9,518) in the irrigation group were lower than the control group (62,119±11,101) (P=0.014) (Figure 2). The incidence of superficial SSIs in the irrigation group was significantly smaller than in the control group [control group 15/61 (24.6%) and irrigation group 3/58 (5.2%); P=0.003] (Table 3).

Table 1

| Variable | Control group (n=61) | Irrigation group (n=58) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 60.3±11.1 | 58.2±10.6 | 0.288 |

| Gender, male/female | 33/28 | 32/26 | 0.906 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 24.0±2.53 | 23.7±2.65 | 0.513 |

| DM, absence/presence | 35/26 | 38/20 | 0.362 |

| Albumin, mean ± SD | 37.3±4.0 | 37.2±4.0 | 0.917 |

| Albumin (≤35 g/L), absence/presence | 51/10 | 49/9 | 0.896 |

| Hemoglobin, mean ± SD | 101.8±25.9 | 100.9±20.3 | 0.838 |

| Hemoglobin, (≤90 g/L), absence/presence | 28/33 | 25/33 | 0.759 |

| Tumorous obstruction, absence/presence | 55/6 | 52/6 | 0.927 |

| Location, colon/rectum | 33/28 | 39/19 | 0.143 |

BMI, body mass index.

Table 2

| Variable | Control group (n=61) | Irrigation group (n=58) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical procedure | 0.332 | ||

| Right hemicolectomy | 17 (27.9%) | 19 (32.8%) | |

| Left hemicolectomy and sigmoidectomy | 16 (26.2%) | 20 (34.5%) | |

| Anterior resection | 28 (45.9%) | 19 (32.8%) | |

| Operating time (min), mean ± SD | 136.6±25.4 | 134±21.5 | 0.556 |

| Blood loss (mL), mean ± SD | 86.6±108.7 | 103±131 | 0.471 |

| Wound length (cm), mean ± SD | 18.9±2.4 | 19.4±4.7 | 0.498 |

| TSF (cm), mean ± SD | 2.37±0.45 | 2.53±0.59 | 0.115 |

| Stoma, absence/presence | 54/7 | 52/6 | 0.843 |

| Postoperative complication | 16/45 | 13/45 | 0.628 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 5 (8.2%) | 5 (8.6%) | |

| Anastomotic bleeding | 4 (6.6%) | 2 (3.4%) | |

| Pneumonia | 7 (11.5%) | 6 (10.3%) | |

| Mortality | 1 | 0 | 1.000 |

TSF, thickness of subcutaneous fat.

Table 3

| Variable | Control group (n=61) | Irrigation group (n=58) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial SSIs | 15 (24.6%) | 3 (5.2%) | 0.003 |

| Deep SSIs | 7 (11.5%) | 2 (3.4%) | 0.164 |

| Incisional SSIs | 22 (36.1%) | 5 (8.6%) | 0.001 |

| Incision dehiscence | 3 (4.9%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0.619 |

| Inpatient stay | 9.64±4.15 | 12.26±5.55 | 0.004 |

| Hospitalization expenses | 57,356±9,518 | 62,119±11,101 | 0.014 |

SSIs, incisional surgical site infections.

Discussion

SSIs is a big burden for health-care systems, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries. There are about 40,000,000 people in Fujian Province, China. As one of the largest gastrointestinal surgery department in our province, there are about 800–1,200 cases of colorectal surgery each year. Incisional SSIs is a common complication of colorectal surgery. Therefore, how to prevent incisional infection is a key clinical problem we have to face every day.

Many studies have reported several independent risk factors that are associated with the incidence of incisional SSIs after colorectal surgery. These risk factors include diabetes mellitus (11), preoperative hypoalbuminemia (7), preoperative anemia (12), wound classification (13-15), the subcutaneous fat thickness (2), and so on. These patients who had diabetes mellitus, hypoalbuminemia (ALB ≤35 g/L), anemia (Hb ≤90 g/L) or tumorous obstruction before operation have a high rate of incisional infection, therefore We chose these types of patients to enroll our study in order to improve the contrast of incisional SSIs rate in the two groups. The drainage tube is not suitable for thin patients. Therefore we chose the patients with the thickness of the subcutaneous fat greater than 1.5 cm.

Many retrospective studies have reported that subcutaneous drainage reduces wound infection in abdominal surgery, which has a high risk of wound infection (9,16,17). Baier et al. have reported that the subcutaneous drainage system was not effective in gastrointestinal surgeries (10,18-20). In addition, a drainage tube as a foreign body may increase bacterial infections and result in wound infection. Therefore, the effect of the subcutaneous drainage in the colorectal surgery to prevent the SSIs is controversial.

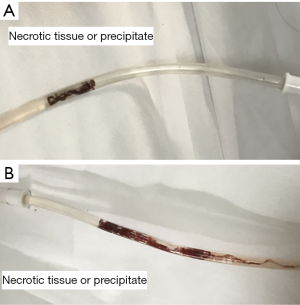

Subcutaneous fat is easy to necrosis and liquefaction after dissection (especially using the electric knife) and suture (21), and lots of studies have shown that obesity is a high-risk factor for incisional infection (22). The presence of liquid and necrotic tissue in the subcutaneous layer is considered to promote the growth of intestinal bacteria, resulting in increased SSI. In this environment, the intestinal bacteria from the colorectal tract are easy to proliferate, especially in patients with low immunity (20). Some studies have shown that the incisional infection of colorectal surgery was evident at 3–5 days after surgery (23). Therefore, the early stage after surgery is an important period for SSIs. The prevention in this period is critical. It is believed that wound infection would be reduced if the liquid and necrotic tissue that would induce the proliferation of bacteria earlier after surgery can be removed effectively. Therefore if the placement of a subcutaneous suction drainage tube could clear the effusion and necrotic tissue effectively, the incidence of incisional SSIs should be reduced sharply. However, we found that the rate of incisional SSIs did not decrease significantly in the subcutaneous suction drainage patients in our center. The main reason may be that subcutaneous suction drainage is more prone to develop blockages by necrotic tissue (Figure 3). In our study, we found that intermittent irrigation could effectively prevent drainage tube blockage. The saline could effectively wash away the necrotic tissues under the pressure of negative pressure ball.

Most of the bacteria in the colorectal incision are anaerobes. When the head of the irrigation tube was opened, the irrigation tube and the drainage tube could form an effective airflow under the pressure of the negative pressure ball. Oxygen in the air could effectively inhibit the growth of anaerobes. The calcium hypochlorite and boric acid solution can effectively kill the bacteria when it contacts the tissue. We often use it to wash the wound or fill the wound with gauze, so it could effectively kill the residual bacteria in the drainage tube. Therefore, the subcutaneous suction drainage and intermittent irrigation can effectively drain the effusion and necrotic tissue in the incision, avoid blockage of the drainage tube. Oxygen in the air and the calcium hypochlorite and boric acid solution can effectively inhibit and kill residual bacteria in the incision so as to effectively control the infection rate of the incisional wound. Because of the relatively backward medical environment, equipment, and technology, the rate of incisional infection in developing countries is 2–5 times higher than that of the developed countries (24,25). The method in our study is simple and cheap. Therefore it is suitable for implementation in developing countries.

There are some problems existing in this method. First of all, it is the blockage of the tube (the irrigation tube or drainage tube). There were two patients in the subcutaneous tube group had tube blockage, and the drainage tube could not be washed. This may be related to the first irrigation time and interval of the drainage tube. Second, the negative pressure ball is simple and crude, the pressure is not easy to control. Therefore we need new equipment which can maintain constant pressure, and the pressure is adjustable. Third, although this method can effectively reduce the infection rate of incision, there is still a certain rate of infection. Therefore we need a multicenter and larger sample of clinical research to evaluate this method further.

This study shows that the subcutaneous suction drainage and intermittent irrigation is safe and effective to prevent incisional SSIs in radical colorectal surgery. In addition, it is simple and cheap. Therefore it is suitable for implementation in low-income and middle-income countries.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The present study was supported by

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2019.12.32). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Hospital Affiliated to Fujian Medical University (No. 2015084), and informed consent was obtained according to institutional regulations. Written informed consent for further clinical research was obtained from participants who used the new method for their clinical records.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Allegranzi B, Zayed B, Bischoff P, et al. New WHO recommendations on intraoperative and postoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:e288-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujii T, Tsutsumi S, Matsumoto A, et al. Thickness of Subcutaneous Fat as a Strong Risk Factor for Wound Infections in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Impact of Prediction Using Preoperative CT. Dig Surg 2010;27:331-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JS, Terjimanian MN, Tishberg LM, et al. Surgical site infection and analytic morphometric assessment of body composition in patients undergoing midline laparotomy. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213:236-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, et al. Elective colon and rectal surgery differ in risk factors for wound infection: results of prospective surveillance. Ann Surg 2006;244:758-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bullard KM, Trudel JL, Baxter NN, et al. Primary perineal wound closure after preoperative radiotherapy and abdominoperineal resection has a high incidence of wound failure. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:438-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Panici PB, Zullo MA, Casalino B, et al. Subcutaneous drainage versus no drainage after minilaparotomy in gynecologic benign conditions: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:71-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hennessey DB, Burke JP, Ni-Dhonochu T, et al. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is an independent risk factor for the development of surgical site infection following gastrointestinal surgery: a multi-institutional study. Ann Surg 2010;252:325-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colli A, Camara ML. Correction: first experience with a new negative pressure incision management system on surgical incisions after cardiac surgery in high risk patients. J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;7:37. [Crossref]

- Watanabe J, Ota M, Kawamoto M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of subcutaneous closed-suction Blake drains for the prevention of incisional surgical site infection after colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017;32:391-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baier PK, Glück NC, Baumgartner U, et al. Subcutaneous Redon drains do not reduce the incidence of surgical site infections after laparotomy. A randomized controlled trial on 200 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 2010;25:639-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krieger BR, Davis DM, Sanchez JE, et al. The use of silver nylon in preventing surgical site infections following colon and rectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:1014-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malone DL, Genuit T, Tracy JK, et al. Surgical site infections: reanalysis of risk factors. J Surg Res 2002;103:89-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Romy S, Eisenring MC, Bettschart V, et al. Laparoscope use and surgical site infections in digestive surgery. Ann Surg 2008;247:627-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang R, Chen HH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after elective resection of the colon and rectum: a single-center prospective study of 2,809 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 2001;234:181. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Young H, Knepper B, Moore EE, et al. Surgical site infection after colon surgery: National Healthcare Safety Network risk factors and modeled rates compared with published risk factors and rates. J Am Coll Surg 2012;214:852-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chowdri NA, Qadri SA, Parray FQ, et al. Role of subcutaneous drains in obese patients undergoing elective cholecystectomy: a cohort study. Int J Surg 2007;5:404-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujii T, Tabe Y, Yajima R, et al. Effects of subcutaneous drain for the prevention of incisional SSI in high-risk patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011;26:1151-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lauscher JC, Schneider V, Lee LD, et al. Necessity of subcutaneous suction drains in ileostomy reversal (DRASTAR)—a randomized, controlled bi-centered trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2016;401:409-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Imada S, Noura S, Ohue M, et al. Efficacy of subcutaneous penrose drains for surgical site infections in colorectal surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013;5:110-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hellums EK, Lin MG, Ramsey PS. Prophylactic subcutaneous drainage for prevention of wound complications after cesarean delivery - a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197:229. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braakenburg A, Obdeijn MC, Feitz R, et al. The clinical efficacy and cost effectiveness of the vacuum-assisted closure technique in the management of acute and chronic wounds: a randomized controlled trial. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;118:390-7; discussion 398-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dindo D, Muller MK, Weber M. Obesity in general elective surgery. Lancet 2003;361:2032-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhuang J, Ye J, Huang Y, et al. Application of postoperational CT scan in the early diagnosis of incisional surgical site infections in elective colorectal surgery. Int J Clin Exp Med 2017;10:9954-62.

- Allegranzi B, Bagheri NS, Combescure C, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011;377:228-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alp E, Altun D, Ulu-Kilic A, et al. What really affects surgical site infection rates in general surgery in a developing country? J Infect Public Health 2014;7:445-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]