Metastasectomy could not improve the survival of metastatic urothelial carcinoma: evidence from a meta-analysis

Introduction

Urinary epithelial cancer is the most important pathological type in urinary system tumors, and about 95% of bladder cancers are urothelial cancer. Among male cancer patients in the United States, bladder cancer ranks the eighth highest mortality rate (1). Especially for metastatic urothelial cancer, the 5-year survival rate of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma is only 5% due to the lack of effective treatment. Currently, systemic chemotherapy combining methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) or gemcitabine plus cisplatin (GC) is still the standard first-line regiments for treating metastatic urothelial carcinoma patients who cannot be cured by radiotherapy or surgery alone. For those who are not sensitive to cisplatin-based chemotherapy, chemotherapy combining gemcitabine and carboplatin can also be applied (2). As for metastatic urothelial cancer, the response rate of these patients to platinum-based combined chemotherapy regimens is as high as 40–70%, however their overall 5-year survival rate is less than 15% (3-5). Even if a complete response has been achieved at the beginning of chemotherapy, a progressive disease (PD), partial response (PR) or stable disease (SD) is the inevitable outcome with the advancement of treatment. In addition, systemic chemotherapy has serious heart, liver, and kidney toxic side effects. For patients who cannot tolerate, it is necessary to reconsider treatment options.

Recently, the role of immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with metastatic urothelial cancer has begun to attract more and more attention. Due to the lack of evidence for clinical practice, whether or not it can be utilized as first-line treatment for metastatic urothelial cancer remains unclear (6). With the advancement of surgical techniques and instruments, surgeries have been increasingly applied to metastatic urothelial carcinoma patients and more clinical practices have been published. Accumulating data had pointed out that survival benefits from metastasectomy/cystectomy could be obtained in proper patients, especially in patients with lung metastases (7,8). However, several researchers also suggested that patients who underwent salvage surgery might gain no significant survival advantage (9,10), comparing with those who accepted other treatment strategies. It still remained controversial whether or not the surgical method could be utilized as a treatment plan to improve the survival benefits of metastatic urothelial cancer. Hence, this study was conducted to clarify the roles of surgeries in metastatic urothelial carcinoma by means of overall survival (OS) or cancer-specific/progression-free survival (CSS/PFS) based on available data. Moreover, our results were anticipated to provide some references for future clinical work.

Methods

Search strategy

Eligible studies were conducted by comprehensively searching three online databases (PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science), published before May 1st, 2019. The search strategy was displayed as follows: (“metastatic urothelial carcinoma” or “metastatic bladder cancer” or “locally advanced bladder cancer” or “lymph node positive bladder cancer”) and (“metastasectomy” or “metastasis resection” or “radical cystectomy” or “aborted radical cystectomy” or “cytoreductive radical cystectomy”). All eligible articles were selected as follows: (I) English articles; (II) metastatic urothelial carcinoma patients; (III) patients underwent metastasectomy/cystectomy; (IV) independent surgical or non-surgical cohort studies; (V) sufficient data for extraction. Meanwhile, the exclusive criteria were detailed as follows: (I) non-English articles; (II) studies not related to metastatic urothelial carcinoma; (III) without surgical or non-surgical cohort studies; (IV) unavailable data for analysis.

Data extraction

All available data were extracted independently by two investigators and a third investigator would join in to make an appropriate decision when disagreement existed. The extracted variables from included studies were recorded as follows: author’s name, year, median or mean age, ethnicity, study design, survival analysis, months of follow-up, number of patients, treatment, hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), source of HR. If HR and its 95% CI could not be obtained from the original studies, data would be extracted from Kaplan-Meier curves by using previously published methods (11,12).

Quality assessment

All enrolled studies were rated for methodological quality by two investigators independently according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm) (13). Therein, total scores of quality evaluation ranged from 0 to 9 and if a study got the final score >6, it was regarded as high quality. Detail information of each study was presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Studies | Year | Quality indicators from Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | Scores | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Dong | 2017 | ★ | ★ | – | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Abe | 2017 | ★ | ★ | – | ★ | ★★ | – | ★ | ★ | 7 |

| Galsky | 2016 | ★ | – | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Necchi | 2015 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | – | ★ | – | 7 |

| Bekku | 2013 | – | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | – | ★ | ★ | 7 |

| Fokas | 2010 | ★ | – | – | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | – | 6 |

| Als | 2007 | – | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | – | – | ★ | 6 |

| Abe | 2007 | – | – | ★ | ★ | ★★ | – | ★ | ★ | 6 |

1, representativeness of the exposed cohort; 2, selection of the non-exposed cohort; 3, ascertainment of exposure; 4, outcome of interest not present at start of study; 5, control for important factor or additional factor; 6, assessment of outcome; 7, follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur; 8, adequacy of follow up of cohorts. ★, each quality choice could be awarded a maximum of one star except for the numbered 5 item which could be granted a maximum of two stars. If the final score >6 stars, we regarded it as high quality.

Statistical analysis

Relationships between surgery and metastatic urothelial carcinoma were analyzed by CSS/PFS or OS based on the relevant literature. Heterogeneity assessment was conducted by Chi-square test and I-square test. While Chi-square test P<0.1 or I2>50%, it was considered to be significant heterogeneity. The random-effects model or the fixed-effects model was applied respectively according to the presence or absence of significant heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the stability and reliability of our results in this meta-analysis. Furthermore, Begg’s funnel plot was adopted to check out the potential publication bias. If P<0.05, it meant there was publication bias (14). Besides, P<0.05 was thought to be statistically significant. All above statistical analyses were conducted by Stata 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Studies characteristics

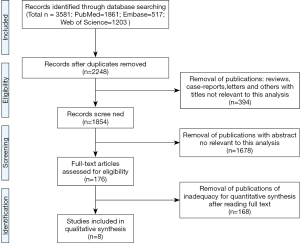

A total of 3,581 relevant studies were initially identified by a primary search of three online databases and relevant reference lists based on the strategy above. According to our inclusive and exclusive criteria, 3,573 records were excluded and 8 articles were ultimately adopted for a further evaluation in the present meta-analysis accruing from March 2007 to November 2017 (15-22). Detailed literature searching and selecting process was described in Figure 1.

Among these eligible eight studies (Table 2), multivariate Cox regression analysis of prognostic factors influencing OS and CSS was utilized by Dong et al., while Necchi and Bekku et al. focused on the OS and PFS. The other five articles only reported the OS of patients underwent surgical consolidation using multivariate or univariable analysis. When taking the treatment regimens into account, Dong and Abe et al. divided the surgical cohort into metastasectomy (MC) vs. non-surgical therapy (NS) cohort and radical cystectomy (RC) vs. NS cohort respectively, while the others concentrated only one cohort. Amongst them, Galsky, Necchi and Als et al. discussed RC vs. NS cohort, and Bekku, Fokas and Abe discussed MC vs. NS cohort. Four articles provided the data directly. For other articles that did not provide data, we extracted them from Kaplan-Meier curves.

Table 2

| First author | Publish year | Median or mean age | Dominant ethnicity | Study design | Survival analysis | Months of follow-up | Number of patients | Treatment | HR (95% CI) | Source of HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dong1,3 | 2017 | 70 | White, Black, others | R | OSM | 0–59 | 1,862 | RC/NS | 0.6 (0.44–0.818) | Reported |

| Dong1,4 | 2017 | 70 | White, Black, others | R | CSSM | 0–59 | 1,862 | RC/NS | 0.632 (0.462–0.865) | Reported |

| Dong2,3 | 2017 | 70 | White, Black, others | R | OSM | 0–59 | 1,862 | MC/NS | 1.157 (0.705–1.898) | Reported |

| Dong2,4 | 2017 | 70 | White, Black, others | R | CSSM | 0–59 | 1,862 | MC/NS | 1.184 (0.712–1.969) | Reported |

| Abe1 | 2017 | 67 | NA | R | OSM | >60 | 228 | RC/NS | 0.81 (0.58–1.131) | Reported |

| Abe2 | 2017 | 67 | NA | R | OSM | >60 | 228 | MC/NS | 0.364 (0.171–0.68) | Reported |

| Galsky | 2016 | NA | White, Black, others | R | OSM | 0–60 | 1,376 | RC/NS | 0.752 (0.654–0.855) | Reported |

| Necchi3 | 2015 | 59 | NA | R | OSM | >60 | 59 | RC/NS | 0.30 (0.13–0.70) | Reported |

| Necchi5 | 2015 | 59 | NA | R | PFSM | >60 | 59 | RC/NS | 0.31 (0.14–0.67) | Reported |

| Bekku3 | 2013 | 64 | NA | R | OSU | 4.5–66 | 27 | MC/NS | 0.69 (0.12–5.21) | SC |

| Bekku5 | 2013 | 64 | NA | R | PFSU | 4.5–66 | 27 | MC/NS | 0.36 (0.08–1.63) | SC |

| Fokas | 2010 | NA | NA | R | OSU | >60 | 62 | MC/NS | 0.95 (0.47–1.9) | SC |

| Als | 2007 | NA | NA | R | OSU | >60 | 20 | RC/NS | 0.45 (0.08–3.38) | SC |

| Abe | 2007 | 66 | NA | R | OSM | >60 | 48 | MC/NS | 0.55 (0.21–1.41) | SC |

1, the treatment group of RC vs. NS. 2, the treatment group of MC vs. NS. 3, the survival analysis of OS. 4, the analysis of CSS. 5, the analysis of PFS. NA, not available; R, retrospective study; OS, overall survival; CSS, cancer specific survival; PFS, progression free survival; U, univariate analysis; M, multivariate analysis; RC, radical cystectomy; MC, metastasectomy; NS, non-surgery; SC, survival curves.

OS associated with surgery

These enrolled five studies indicated that OS is positively associated with the patients underwent RC by fixed-effects model based on the low heterogeneity (P=0.158, I2=39.4%). This result successfully demonstrated that patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma could benefit from RC (pooled HR =0.72, 95% CI, 0.64–0.81) (Figure 2A). However, our results didn’t predict the significant associations between OS and the patients underwent MC (P=0.093, I2=49.7%), which meant the MC had little impact on prognosis (pooled HR =0.78, 95% CI, 0.56–1.08) (Figure 2B).

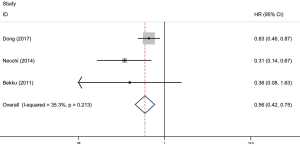

CSS/PFS associated with surgery

Among these included literatures, there were three articles reporting on CSS/PFS, one of which was about CSS and the other two were about PFS. In these studies, Dong and Necchi et al. focused on RC vs. NS cohort while Bekku focused on MC vs. NS cohort. Merging the above data as surgery vs. NS cohort, we finally got a significant conclusion that patients could gain survival benefit from the surgery (RC or MC) taking into account CSS/PFS together (P=0.213, I2=35.3%, pooled HR =0.56, 95% CI, 0.42–0.75) (Figure 3).

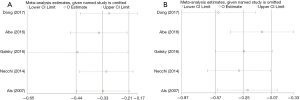

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the stability and reliability of the results of this meta-analysis. In RC vs. NS cohort or MC vs. NS cohort on, the sensitivity analysis for the result of salvage surgeries and OS did not alter significantly, demonstrating that no single study could significantly influence the pooled HR or the 95% CI (Figure 4). Overall, our results were stability and reliability.

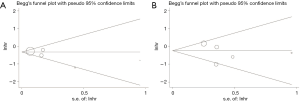

As displayed in Figure 5, the P value of Begg’s test was 0.462 and the P value of Egger’s test was 0.200 in the pooled analysis of RC vs. NS cohort based on OS. In the pooled analysis of MC vs. NS cohort based on OS, the P value of Begg’s test and Egg’s test was 0.806 and 0.509 respectively. P values were all above 0.05, indicating no evidence of significant publication bias in this article.

Discussion

Although the first-line combination chemotherapy scheme has been continuously improved, the treatment of metastatic urothelial cancer has not achieved great progress over several decades (3). Despite the arrival of immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors (23), as the terminal stage of bladder cancer, metastatic urothelial carcinoma has rather lower survival rates after its diagnosis. Traditionally, surgery remains the treatment for the patients with malignancy in an appropriate condition such as early stage of tumor without metastasis. It was still elusive whether or not patients suffering from metastatic urothelial carcinoma could benefit from surgeries aiming to excise the primary or metastatic lesion. Moreover, clinical researchers are also paying more attention to the roles of surgical treatment in metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Since the early 1980s, postchemotherapy surgery with curative intent had been tried (24). In 2001, Herr and colleagues indicated that RC and pelvic lymph node dissection could be a consolidative intervention in patients experiencing complete or significant response to induction systemic CHT (25). Many other studies had also evaluated the roles of surgical resection of metastatic deposits as a part of a multidisciplinary approach (26-31). However, most researches were based on small sample sizes or single-institutional studies or in the absence of stable and reliable conclusions. Therefore, meta-analysis, as a powerful tool in providing favorable suggestions was carried out to clarify the merits of surgeries for metastatic urothelial carcinoma. The present study was the first to shed light on the relationships between surgical treatment and metastatic urothelial carcinoma in terms of OS or CSS/PFS. Subsequently sensitivity analysis and publication bias manifested robustness of this study.

As for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma or high-risk non-muscle invasive disease refractory to instillation therapy, RC associated with pelvic lymph node dissection was the gold standard treatment. For patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma, RC was considered to be cytoreductive surgery (32). In the other urologic tumor, metastatic prostate cancer patients with oligometastatic sites could also benefit from radical prostatectomy (33). Similarly, in metastatic urothelial carcinoma, researchers indicated that surgery might contribute to long-term disease-free survival in selected patients (25,34). Moreover, our study successfully demonstrated the feasibility of RC surgery and the survival benefit of improving OS. For its advantages of prognosis, cytoreductive RC had also been recognized by other researchers (5,35). Our findings on RC were consistent with previous studies. For instance, Seisen et al. (36) shed light on that OS was better when local treatment was performed after systemic CHT by using the National Cancer Database.

Since the primary lesion cannot be removed, whether or not metastasectomy could benefit metastatic urothelial carcinoma patients remained a debate. Matsuguma et al. (7) emphasized that pulmonary metastasectomy could have a curative role in metastatic cases. Another study carried out by Lehmann et al. (34) thought that survival benefits could be achieved in patients following surgical removal of metastases including retroperitoneal lymph nodes, distant lymph, lung, bone, adrenal gland, brain, small intestine and subcutaneous. The forest map of a newly published systematic review also pointed out that improved OS was shown in patients treated with metastasectomy compared with nonsurgical treatment of metastatic lesions (18). However, our results concluded that no improving OS was observed for patients treated with metastasectomy (HR =0.78, 95% CI, 0.56–1.08). This might attribute to two aspects of reasons: on the one hand, surgical cohort were divided into RC vs. NS cohort and MC vs. NS cohort in the present study and analysis of stratified data was performed respectively, while the former meta-analysis merely mixed two different surgical regimens into one; on the other hand, our study recruited recently published studies revealing more comprehensive data of individual patient with different metastatic lesions.

Although our results indicated that MC could not improve the survival benefits of metastatic urothelial carcinoma, is there any difference among different metastatic sites? The different effect of metastatic sites on patients’ prognosis had been discussed in several previous studies (37,38). Without specifying which kind of metastases played roles, Taguchi et al. (39) pointed out that patients with visceral metastasis might have prognostic values for outcomes. Abe et al. (16) conducted a multivariate analysis on pretreatment prognostic characteristics and identified that single organ metastasis was associated with prolonged OS. As for distant metastatic sites, Dong et al. (15) revealed that bone and lung metastases could be independent prognostic factors, whereas distant lymph node metastases or multi-site metastases were not an independent prognostic indicator for both OS and bladder cancer specific survival.

To the best of our knowledge, it was the first for us to shed light on the relationships between surgical treatment and metastatic urothelial carcinoma in terms of OS or CSS/PFS. Before fully understanding this article, some assignable limitations should not be ignored. On the one hand, more literature with sufficient data should be involved in the study to disclose the independent prognostic factor of metastatic urothelial carcinoma and CSS/PSF of patients underwent different surgeries. On the other hand, upcoming prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were warranted to provide more available data to elaborate the efficacy.

Conclusions

Although our results shed light on the positive roles of RC in the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma, MC surgery displayed no effect on the OS. This was contrary to usual clinical work, indicating that metastatic urothelial carcinoma patients could not gain survival benefits from MC. Our results were anticipated to provide some references for further clinical work. Subsequent prospective RCTs were also required to provide more evidence to elaborate the efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the researchers and study participants for their contributions.

Funding: This work was supported by

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2020.01.42). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Necchi A, Pond GR, Raggi D, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Gemcitabine Plus Either Taxane or Carboplatin in the First-Line Setting of Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2017;15:23-30.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4602-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bamias A, Tzannis K, Bamia C, et al. The Impact of Cisplatin- or Non-Cisplatin-Containing Chemotherapy on Long-Term and Conditional Survival of Patients with Advanced Urinary Tract Cancer. Oncologist 2019;24:1348-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alfred Witjes J, Lebret T, Comperat EM, et al. Updated 2016 EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol 2017;71:462-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feld E, Harton J, Meropol NJ, et al. Effectiveness of First-line Immune Checkpoint Blockade Versus Carboplatin-based Chemotherapy for Metastatic Urothelial Cancer. Eur Urol 2019;76:524-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuguma H, Yoshino I, Ito H, et al. Is there a role for pulmonary metastasectomy with a curative intent in patients with metastatic urinary transitional cell carcinoma? Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:449-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim T, Ahn JH, You D, et al. Pulmonary Metastasectomy Could Prolong Overall Survival in Select Cases of Metastatic Urinary Tract Cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2015;13:e297-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Otto T, Krege S, Suhr J, et al. Impact of surgical resection of bladder cancer metastases refractory to systemic therapy on performance score: a phase II trial. Urology 2001;57:55-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abe T, Matsumoto R, Shinohara N. Role of surgical consolidation in metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Curr Opin Urol 2016;26:573-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007;8:16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watkins C, Bennett I. A simple method for combining binomial counts or proportions with hazard ratios for evidence synthesis of time-to-event data. Res Synth Methods 2018;9:352-60. [PubMed]

- Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dong F, Shen Y, Gao F, et al. Prognostic value of site-specific metastases and therapeutic roles of surgery for patients with metastatic bladder cancer: a population-based study. Cancer Manag Res 2017;9:611-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abe T, Ishizaki J, Kikuchi H, et al. Outcome of metastatic urothelial carcinoma treated by systemic chemotherapy: Prognostic factors based on real-world clinical practice in Japan. Urol Oncol 2017;35:38.e1-38.e8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galsky MD, Stensland K, Sfakianos JP, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Treatment Strategies for Bladder Cancer With Clinical Evidence of Regional Lymph Node Involvement. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2627-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Necchi A, Giannatempo P, Lo Vullo S, et al. Postchemotherapy lymphadenectomy in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: long-term efficacy and implications for trial design. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2015;13:80-6.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bekku K, Saika T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Could salvage surgery after chemotherapy have clinical impact on cancer survival of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma? Int J Clin Oncol 2013;18:110-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fokas E, Henzel M, Engenhart-Cabillic R. A comparison of radiotherapy with radiotherapy plus surgery for brain metastases from urinary bladder cancer: analysis of 62 patients. Strahlenther Onkol 2010;186:565-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Als AB, Sengelov L, von der Maase H. Long-term survival after gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with locally advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: focus on supplementary treatment strategies. Eur Urol 2007;52:478-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abe T, Shinohara N, Harabayashi T, et al. Impact of multimodal treatment on survival in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. Eur Urol 2007;52:1106-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sonpavde G. PD-1 and PD-L1 Inhibitors as Salvage Therapy for Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1073-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cowles RS, Johnson DE, McMurtrey MJ. Long-term results following thoracotomy for metastatic bladder cancer. Urology 1982;20:390-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herr HW, Donat SM, Bajorin DF. Post-chemotherapy surgery in patients with unresectable or regionally metastatic bladder cancer. J Urol 2001;165:811-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa T, Hara T, Kawahara T, et al. Prognostic risk stratification of patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder with recurrence after radical cystectomy. J Urol 2013;189:1275-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siefker-Radtke AO, Walsh GL, Pisters LL, et al. Is there a role for surgery in the management of metastatic urothelial cancer? The M. D. Anderson experience. J Urol 2004;171:145-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luzzi L, Marulli G, Solli P, et al. Long-Term Results and Prognostic Factors of Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Patients with Metastatic Transitional Cell Carcinoma. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;65:567-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Vries RR, Nieuwenhuijzen JA, Meinhardt W, et al. Long-term survival after combined modality treatment in metastatic bladder cancer patients presenting with supra-regional tumor positive lymph nodes only. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009;35:352-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu NW, Murray KS, Donat SM, et al. The Outcome of Post-Chemotherapy Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection in Patients with Metastatic Bladder Cancer in the Retroperitoneum. Bladder Cancer 2019;5:13-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zargar-Shoshtari K, Zargar H, Lotan Y, et al. A Multi-Institutional Analysis of Outcomes of Patients with Clinically Node Positive Urothelial Bladder Cancer Treated with Induction Chemotherapy and Radical Cystectomy. J Urol 2016;195:53-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials: by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d'Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l'Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer 2009;115:1234-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandaglia G, Fossati N, Stabile A, et al. Radical Prostatectomy in Men with Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer: Results of a Single-institution Series with Long-term Follow-up. Eur Urol 2017;72:289-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lehmann J, Suttmann H, Albers P, et al. Surgery for metastatic urothelial carcinoma with curative intent: the German experience (AUO AB 30/05). Eur Urol 2009;55:1293-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galsky MD, Domingo-Domenech J, Sfakianos JP, et al. Definitive Management of Primary Bladder Tumors in the Context of Metastatic Disease: Who, How, When, and Why? J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3495-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seisen T, Sun M, Leow JJ, et al. Efficacy of High-Intensity Local Treatment for Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: A Propensity Score-Weighted Analysis From the National Cancer Data Base. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3529-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu SG, Li H, Tang LY, et al. The effect of distant metastases sites on survival in de novo stage-IV breast cancer: A SEER database analysis. Tumour Biol 2017;39:1010428317705082. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oweira H, Petrausch U, Helbling D, et al. Prognostic value of site-specific metastases in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:1872-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taguchi S, Nakagawa T, Uemura Y, et al. Validation of major prognostic models for metastatic urothelial carcinoma using a multi-institutional cohort of the real world. World J Urol 2016;34:163-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]