Positive lymph node ratio as a novel indicator of prognosis in gastric signet ring cell carcinoma: a population-based retrospective study

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignancies, second only to lung cancer, breast cancer and colorectal cancer, but the mortality rate of GC ranks third among malignant tumors (1). Due to the popularity of Helicobacter pylori eradication, the incidence of GC has fallen off. However, epidemiological investigations have recently found that the incidence of diffuse gastric cancer, especially signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC), is significantly rising (2-4). Because the pathogenesis of SRCC and precancerous lesions are not clear, the diagnosis of early tumors is difficult and it is generally found to be in stage III or IV of advanced cancer (4).

The status of lymph node plays a strong predictive role in the prognosis of patients with GC (5), and how to formulate a therapeutic regimen for metastatic lymph nodes is a crucial clinical problem. Although the zeal for optimal lymph node dissection is inconsistent in the East and West, radical lymph node dissection is still admitted as an important strategy for the tumor removal of GC (6). In various cancers, the positive lymph node ratio (PLNR), which is calculated by dividing the number of metastatic lymph nodes by the number of lymph nodes retrieved, has been studied as a trustworthy prognostic factor (7-9). Especially in Western countries, only a small amount of lymph nodes can be obtained after gastrectomy for GC, resulting in some patients not being able to adequately staged. Therefore, it is necessary to explore whether PLNR can be well applied to the prediction of GC prognosis. In fact, Shuhei Komatsu found that PLNR is conducive to stratifying the prognosis and assessing the extent of local malignancy resection of pN3 GC (10). In our study, we used retrospective data to study whether PLNR can as a prognostic factor in SRCC patients in the US population and our findings may show evidence that PLNR is an excellent system for describing prognosis for SRCC patients.

Methods

Patient selection

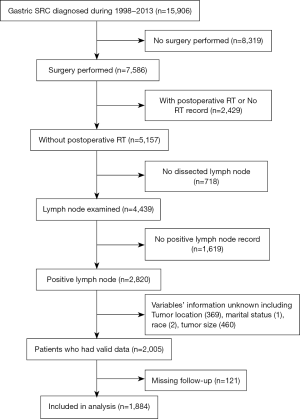

The protocol of our study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital of Fudan University. Due to the nature of the retrospective study, informed consent is not required. The data source is the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database of the National Cancer Institute (https://seer.cancer.gov/), which documents information on morbidity, mortality, and prevalence of millions of malignancies in USA. We identified patients who submitted to the SEER database in November 2016 for this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) The patient’s diagnosis period is from 1998 to 2013; (II) the site code of 3rd edition International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3) is C16.0–C16.9 representing “stomach”; (III) the histological code is signet ring cell carcinoma (8490/3); (IV) primary tumor resection was performed; (V) the patient had not received radiotherapy before surgery; (VI) one or more regional lymph nodes are examined; (VII) The variables’ information of marital status, gender, race, tumor location and tumor size is available; (VIII) information on overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) with survival time were clear. Figure 1 shows the data screening method. We obtained all research data from the SEER-Stat software (SEER*Stat 8.3.6) which is used to download SEER cancer records and generate statistical data to study the influence of cancer on a population. All patients were restaged according SEER historic stage A that is the only variable recording tumor stage information from 1975 to the present. Patient race was grouped into 3 categories: white, black, and others (including American Indian/Alaska native, Asian/Pacific Islander, and unknown).

Statistical analysis

Cutoff values of PLNR were decided using X-tile program, which is used to identify the cutoff with the minimum P values from log-rank χ2 terms of survival (11). We used the Chi-square (χ2) test to compare SRCC patient baseline characteristics. R language packages, “survival” and “coxphf” were used for survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards analysis, respectively. Analyses of Kaplan-Meier log-rank survival test was applied to plotted survival curves and identify differences in survival rates. For the univariate analyses, we used the Cox proportional hazards model method to visualize associations between characteristics and survival. The backward conditional method was used with probability for stepwise entry and removal at 0.05 and 0.10. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Only covariates that were statistically significant on univariate analysis were evaluated on multivariate analysis. The multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was visualized by the nomogram at the end of 3-, 5- and 10-year survival. All data in this work were analyzed utilizing the R version 3.5.2. All statistical tests were performed on two sides.

Results

Baseline demographic

Data from node-positive SRCC patients who have undergone surgery were identified in SEER database, and the clinicopathologic features of all 1,884 cases are shown in Table 1. For the whole study population, the median follow-up time was 62 (range, 1–226) months. A total of 1,220 (64.8%) patients had died of SRCC at the end of follow-up. Among the whole population, 58.3% of the cases were diagnosed at age less than 70 years old, and female is slightly less than male (46.6% vs. 53.4%). 61.3% of the patients were married. As for the distribution of ethnicity in the patients, white patients accounted for 68% of the total population, with the rest being black and others (America Indian/AK Aboriginal, Asian/Pacific Islander). 38.2% of patients have tumors appeared in the distal third of the stomach, accounting for the largest proportion. As for sizes, 52.8% of patients had tumors with diameter greater than 5 cm, and the other is less than or equal to 5 cm. Stage Regional and Distant patients constituted the whole set, with relatively 71.5% and 28.5% of the population. And 52.9% of cohort had more than 15 lymph nodes removed.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Total (%), N=1,884 | PLNR <0.8, N=1,360 (72.2) | PLNR >0.8, N=524 (27.8) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up, 62 (range, 1–226) months | ||||

| Age | 0.664 | |||

| <70 | 1,099 (58.3) | 798 (58.7) | 301 (57.4) | |

| ≥70 | 785 (41.7) | 562 (41.3) | 223 (42.6) | |

| Race | 0.727 | |||

| White | 1,282 (68) | 923 (67.9) | 359 (68.5) | |

| Black | 219 (11.6) | 155 (11.4) | 64 (12.2) | |

| Other‡ | 383 (20.3) | 282 (20.7) | 101 (19.3) | |

| Marital status | 0.477 | |||

| Married | 1,155 (61.3) | 841 (61.8) | 314 (59.9) | |

| Single | 729 (38.7) | 519 (38.2) | 210 (40.1) | |

| Sex | 0.557 | |||

| Female | 878 (46.6) | 640 (47.1) | 238 (45.4) | |

| Male | 1,006 (53.4) | 720 (52.9) | 286 (54.6) | |

| Location | <0.001 | |||

| Proximal third | 303 (16.1) | 236 (17.4) | 67 (12.8) | |

| Mid third | 202 (10.7) | 145 (10.7) | 57 (10.9) | |

| Distal third | 719 (38.2) | 514 (37.8) | 205 (39.1) | |

| Lesser curvature | 289 (15.3) | 223 (16.4) | 66 (12.6) | |

| Greater curvature | 119 (6.3) | 91 (6.7) | 28 (5.3) | |

| Overlapping | 252 (13.4) | 151 (11.1) | 101 (19.3) | |

| Stage | <0.001 | |||

| Distant | 536 (28.5) | 327 (24.0) | 209 (39.9) | |

| Regional | 1,348 (71.5) | 1033 (76.0) | 315 (60.1) | |

| Size | <0.001 | |||

| ≤5 cm | 890 (47.2) | 695 (51.1) | 195 (37.2) | |

| >5 cm | 994 (52.8) | 665 (48.9) | 329 (62.8) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.629 | |||

| No | 1,143 (60.7) | 820 (60.3) | 323 (61.6) | |

| Yes | 741 (39.3) | 540 (39.7) | 201 (38.4) | |

| LNs | <0.001 | |||

| <15 | 887 (47.1) | 598 (44.0) | 289 (55.2) | |

| ≥15 | 997 (52.9) | 762 (56.0) | 235 (44.8) |

SRCC, signet ring cell carcinoma; PLNR, positive lymph nodes ratio. Other‡: Other (American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander).

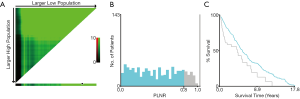

The optimal cutoff value for PLNR count calculated by X-tile

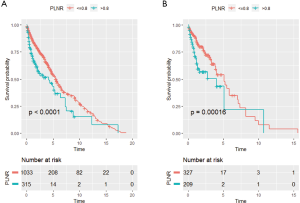

To evaluate the impact of different PLNR count on CSS, the X-tile plots was produced. The maximum value of χ2 log-rank was 33.19 (the number as 0.8, Figure 2, P<0.0001), using 0.8 as the optimal cutoff value to separate the patients into high and low risk subsets in accordance of CSS. As shown in Table 1, the PLNR value of 72.2% patients is less than 0.8. The tumor location, stage, size and the total number of lymph nodes dissected of patients showed a significant difference between patients with PLNR <0.8 or ≥0.8 (P<0.05). Besides, for stage Regional and Distant, we found that patients with PLNR <0.8 had significantly better CSS than those with PLNR ≥0.8 (Both CSS, P<0.001, Figure 3).

Impact of PLNR on survival of SRCC patients

Univariate cox regression analyses on the patients of all the clinical characteristics were conducted to explore their its impact on prognosis (Table 2). Obviously, there was a significant difference in prognosis between the two PLNR groups, regardless of OS or CSS (OS, P<0.001; CSS, P<0.001). Patients with advanced age (≥70 years) had lower OS (P=0.001), and those who were American Indian/AK Native or Asian/Pacific Islander had a better prognosis (OS, P=0.042; CSS, P=0.038). As was expected, the prognosis of patients with stage Regional is significantly better than that of patients with stage Distant (OS, P<0.001; CSS, P<0.001). Additionally, patients with lymph node examined greater than 15 had a significantly better prognosis for OS (P=0.001). Patients with tumor size bigger than 5 cm had a remarkably lower survival (OS, P<0.001; CSS, P<0.001). Remarkably, the prognosis for patients receiving postoperative chemotherapy had got a lot better (OS, P<0.001; CSS, P=0.017).

Table 2

| Characteristics | Overall (OS) | Cancer-specific (CSS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Age | |||||||

| <70 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| ≥70 | 1.267 | 1.15–1.4 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.89–1.12 | 0.999 | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Black | 1.138 | 0.98–1.32 | 0.086 | 1.052 | 0.88–1.25 | 0.575 | |

| Other† | 0.88 | 0.78–1 | 0.042 | 0.858 | 0.74–0.99 | 0.038 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Single | 1.096 | 0.99–1.21 | 0.069 | 1.065 | 0.95–1.2 | 0.286 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Male | 1.044 | 0.95–1.15 | 0.381 | 1.037 | 0.93–1.16 | 0.524 | |

| Location | |||||||

| Proximal third | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Mid third | 0.842 | 0.7–1.02 | 0.076 | 0.854 | 0.68–1.07 | 0.163 | |

| Distal third | 0.885 | 0.77–1.02 | 0.091 | 0.879 | 0.75–1.04 | 0.128 | |

| Lesser curvature | 0.823 | 0.69–0.98 | 0.026 | 0.877 | 0.72–1.07 | 0.193 | |

| Greater curvature | 0.801 | 0.64–1.01 | 0.057 | 0.795 | 0.61–1.04 | 0.095 | |

| Overlapping | 1.098 | 0.92–1.31 | 0.292 | 1.135 | 0.93–1.39 | 0.220 | |

| Stage | |||||||

| Distant | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Regional | 0.531 | 0.48–0.59 | <0.001 | 0.466 | 0.41–0.53 | <0.001 | |

| Size | |||||||

| ≤5 cm | Ref | Ref | |||||

| >5 cm | 1.48 | 1.34–1.63 | <0.001 | 1.7 | 1.52–1.91 | <0.001 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 0.763 | 0.69–0.84 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.78–0.98 | 0.017 | |

| LNs | |||||||

| <15 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| ≥15 | 0.851 | 0.77–0.94 | 0.001 | 0.921 | 0.82–1.03 | 0.150 | |

| PLNR | |||||||

| <0.8 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| >0.8 | 2.391 | 2.15–2.66 | <0.001 | 2.417 | 2.13–2.74 | <0.001 | |

PLNR, positive lymph nodes ratio. Other†: Other (American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander).

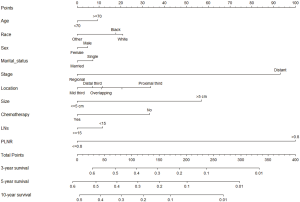

By absorb all the clinical variables into the multivariate cox regression model (Table 3), patients with PLNR >0.8 remained to have a poorer prognosis compared with those with PLNR <0.8 as shown by both OS (HR =2.083, 95% CI: 1.862–2.33, P<0.001) and CSS (HR =2.052, 95% CI: 1.802–2.336, P=0.014). As to other factors, patients more than 70 years revealed lower OS than those less than 70 years old (HR =1.312, 95% CI: 1.184–1.455, P<0.001). Patients in stage Regional had a better prognosis than those in stage Distant (OS, HR =0.55, 95% CI: 0.492–0.615, P<0.001; CSS, HR =0.512, 95% CI: 0.451–0.581, P<0.001). Besides, compared with White, Other races had a better survival (CSS, HR =0.86, 95% CI: 0.743–0.996, P=0.045). Compared with tumors in proximal third, tumors in mid third and distal third had better OS and CSS, and tumors in lesser curvature had better OS. Tumors bigger than 5 cm tend to have a poorer survival (OS, HR =1.351, 95% CI: 1.22–1.497, P<0.001; CSS, HR =1.506, 95% CI: 1.335–1.699, P<0.001). Patients with lymph node examined greater than 15 got a significantly poorer prognosis for OS (HR =0.876, 95% CI: 0.794–0.968, P=0.009). Notably, Patients who received chemotherapy had a better prognosis (OS, HR =0.749, 95% CI: 0.674–0.833, P<0.001; CSS, HR =0.788, 95% CI:0.698–0.89, P<0.001). Based on the above 10 clinical prognostic factors, we constructed a nomogram to deduce the CSS for patients with SRCC (Figure 4).

Table 3

| Characteristics | Overall (OS) | Cancer-specific (CSS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Age | |||||||

| <70 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| ≥70 | 1.312 | 1.184–1.455 | <0.001 | 1.069 | 0.945–1.208 | 0.289 | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Black | 1.085 | 0.934–1.261 | 0.284 | 0.976 | 0.817–1.167 | 0.793 | |

| Other† | 0.886 | 0.782–1.005 | 0.060 | 0.86 | 0.743–0.996 | 0.045 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Single | 1.072 | 0.971–1.183 | 0.171 | 1.053 | 0.938–1.182 | 0.384 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Male | 1.044 | 0.946–1.153 | 0.391 | 1.035 | 0.922–1.161 | 0.561 | |

| Location | |||||||

| Proximal third | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Mid third | 0.762 | 0.628–0.925 | 0.006 | 0.785 | 0.626–0.984 | 0.035 | |

| Distal third | 0.81 | 0.7–0.938 | 0.005 | 0.825 | 0.695–0.98 | 0.028 | |

| Lesser curvature | 0.821 | 0.689–0.977 | 0.027 | 0.909 | 0.743–1.113 | 0.356 | |

| Greater curvature | 0.841 | 0.667–1.06 | 0.143 | 0.852 | 0.649–1.119 | 0.249 | |

| Overlapping | 0.849 | 0.71–1.015 | 0.073 | 0.849 | 0.69–1.045 | 0.123 | |

| Stage | |||||||

| Distant | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Regional | 0.55 | 0.492–0.615 | <0.001 | 0.512 | 0.451–0.581 | <0.001 | |

| Size | |||||||

| ≤5 cm | Ref | Ref | |||||

| >5 cm | 1.351 | 1.22–1.497 | <0.001 | 1.506 | 1.335–1.699 | <0.001 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 0.749 | 0.674–0.833 | <0.001 | 0.788 | 0.698–0.89 | <0.001 | |

| LNs | |||||||

| <15 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| ≥15 | 0.876 | 0.794–0.968 | 0.009 | 0.919 | 0.819–1.033 | 0.157 | |

| PLNR | |||||||

| <0.8 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| >0.8 | 2.083 | 1.862–2.33 | <0.001 | 2.052 | 1.802–2.336 | <0.001 | |

PLNR, positive lymph nodes ratio. Other†: Other (American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander).

Discussion

Over the past decade, despite cancer detection and prevention measures in the United States, the incidence of SRCC has not declined (1,12). This histological subtype of GC may make a difference with the others, and the risk factors for SRCC are not yet clear (3). Lymph node metastasis is recognized as one of the most important factors for prognosis of GC (5). Moreover, lymph node resection for GC remains controversial. Insufficient LN assessment can lead to tumor recurrence and worsening patient survival (10). The European Society of Oncology (ESMO) suggests that the number of lymph nodes evaluated should be more than 16 to prevent the misunderstandings of TNM staging (13). Some studies have shown that with the increase in the number of lymph nodes removed, the survival increased significantly (14).

On the other hand, the immune system will be damaged with excessive resection of lymph nodes, further resulting in other clinical issues, such as being more susceptible to infection. In our study, it was showed that the number of lymph nodes removed of SRCC was greater than 15 in favor of improving OS.

Various clinical factors may affect the number of detected lymph nodes: the degree of lymph node examination pathologically, the degree of lymph node dissection, the surgical condition, and the disparity in the number of congenital lymph nodes among individuals (15). Therefore, the deficiency of retrieved lymph nodes caused by these clinical factors affected our accurate understanding about the prognosis of each patient, affecting further treatment strategies. In summary, finding effective methods of assessment of lymph nodes on survival will elicit more accurate prognostic information. PLNR is useful for the stratification of prognosis and assessment of the extent of local cancer clearance in pN3 GC. In fact, the usefulness of the PLNR cutoff value of 0.4 in lymph node staging has been already revealed (10). In our study, it is clearly showed that the PLNR of 0.8 was the best cutoff value to separate the prognosis of GRCC patients into two cohorts (P<0.001). A PLNR greater than 0.8 was found to be an independent factor of prognosis in patients with SRCC. Moreover, PLNR accurately stratified prognosis at different stages, Reginal and Distant stage. However, there are still many issues to be resolved before the conversion of PLNR into a clinical utility of lymph node staging system in SRCC patients. Our next study will focus on the following areas: expanding the sample size, extending the follow-up time, and controlling the confounding factors, and so on.

Moreover, there are varying opinions on other prognostic variables of SRCC. Some studies have shown that gender, age, tumor location, size, and TNM staging are all significant clinical variables influencing the prognosis of SRCC (12,16). In contrast, a retrospective study of 2,199 patients showed that the prognosis of SRCC was irrelevant to gender, stage and chemotherapy (17). The inconsistency should result from the difference in staging systems, geography and medical level. In our study, the Cox regression analysis showed that age, race, number of lymph node removed, size and location of tumor, and staging were closely associated with SRCC survival as independent prognostic factors. There are many arguments about the role of chemoradiotherapy in GC and SRCC. The Intergroup 0116 trial was the first large-scale randomized trial to show that adjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with gastric cancer who had fully tumor resection was helpful in improving survival (18). In the Western population, the Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy (MAGIC) trial revealed that patients who underwent chemotherapy after surgery had a better prognosis for GC compared with those treated with surgery alone (19). As for SRCC, the ARTIST study and the Intergroup 0116 trial revealed that the efficacy of chemoradiotherapy in diffuse type of GC (including SRC) was low. Nevertheless, Heger et al. (20) found that although SRCC responded poorly to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, it did have a better prognosis. In our study, postoperative chemotherapy did improve patient OS and CSS in positive-node SRCC.

There are several inevitable limitations to our study. First, the SEER database does not cover information that may affect the patient’s prognosis, such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy. Second, different surgical procedures, surgeons and even pathologists will affect the detection rate of total and positive lymph nodes, but SEER did not record this information. Third, this study is a database-based retrospective study, which inevitably lacks data, so it needs to be cautious in practical applications.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that when the PLNR was >0.8, 3-, 5- and 10-year CSS were significantly lower in patients with SRCC who have a lymphadenectomy. PINR remains a novel approach to provide accurate prognostic information and Assistance in the decision-making of clinical diagnosis and treatment for SRCC. Future clinical studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm the role of PLNR in prognosis for SRCC patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2020.04.04). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The protocol of our study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital of Fudan University. Due to the nature of the retrospective study, informed consent is not required.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87-108. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henson DE, Dittus C, Younes M, et al. Differential trends in the intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma in the United States, 1973-2000 - Increase in the signet ring cell type. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004;128:765-70. [PubMed]

- Voron T, Messager M, Duhamel A, et al. Is signet-ring cell carcinoma a specific entity among gastric cancers? Gastric Cancer 2016;19:1027-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pernot S, Voron T, Perkins G, et al. Signet-ring cell carcinoma of the stomach: Impact on prognosis and specific therapeutic challenge. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:11428-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pokala SK, Zhang C, Chen Z, et al. Incidence, Survival, and Predictors of Lymph Node Involvement in Early-Stage Gastric Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma in the US. J Gastrointest Surg 2018;22:569-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bickenbach K, Strong VE. Comparisons of Gastric Cancer Treatments: East vs. West. J Gastric Cancer 2012;12:55-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hou X, Wei JC, Xu Y, et al. The positive lymph node ratio predicts long-term survival in patients with operable thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in China. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:1653-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qian K, Sun W, Guo K, et al. The number and ratio of positive lymph nodes are independent prognostic factors for patients with major salivary gland cancer: Results from the surveillance, epidemiology, and End Results dataset. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:1025-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shang X, Li Z, Lin J, et al. PLNR</=20% may be a benefit from PORT for patients with IIIA-N2 NSCLC: a large population-based study. Cancer Manag Res 2018;10:3561-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Miyamae M, et al. Positive Lymph Node Ratio as an Indicator of Prognosis and Local Tumor Clearance in N3 Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20:1565-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:7252-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwon KJ, Shim KN, Song EM, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer 2014;17:43-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ajani JA, Winter K, Okawara GS, et al. Phase II trial of preoperative chemoradiation in patients with localized gastric adenocarcinoma (RTOG 9904): quality of combined modality therapy and pathologic response. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3953-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith DD, Schwarz RR, Schwarz RE. Impact of total lymph node count on staging and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: data from a large US-population database. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7114-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Degiuli M, De Manzoni G, Di Leo A, et al. Gastric cancer: Current status of lymph node dissection. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:2875-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Cai H, Sheng W, et al. Clinicopathological Characteristics and Survival Outcomes of Primary Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma in the Stomach: Retrospective Analysis of Single Center Database. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144420. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu M, Yang Z, Feng Q, et al. The characteristics and prognostic value of signet ring cell histology in gastric cancer: A retrospective cohort study of 2199 consecutive patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4052. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smalley SR, Benedetti JK, Haller DG, et al. Updated analysis of SWOG-directed intergroup study 0116: a phase III trial of adjuvant radiochemotherapy versus observation after curative gastric cancer resection. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2327-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:11-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heger U, Blank S, Wiecha C, et al. Is preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery the appropriate treatment for signet ring cell containing adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction and stomach? Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:1739-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]