Experience with flap repair after vulvar carcinoma resection: a retrospective observational study of 26 cases

Introduction

Vulvar cancer is a rare type of malignancy, accounting for approximately 5% of all gynecological cancers. Squamous cell carcinomas make up 95% of all vulvar cancers (1). Vulvar cancer has the following characteristics: strong invasion, rapid progression, and easy recurrence. The treatment of vulvar cancer involves extensive vulvar resection or inguinal lymphadenectomy, which often includes extensive resection of at least 2–3 cm around the cancer foci; this can effectively reduce the local recurrence rate (2). However, currently, it is difficult to repair the large wound after resection of vulvar cancer. The main reason for this occurrence is extensive resection, which can lead to a large defect on the skin and soft tissue, especially considering the following factors: the suture tension is very high; the wound can become easily infected after surgery; wound healing is difficult or delayed; scar hyperplasia leads to vaginal orifice stenosis; and sexual ability is reduced or lost after surgery. These factors affect the quality of life of patients (especially young patients). Currently, the repair methods reported and clinically used at home and abroad mainly include skin grafts, skin flaps, fasciocutaneous flaps, and myocutaneous flaps (3). The local and foreign literature provides only rough suggestions for flap repair, and detailed research on different repair strategies for different parts of defects is not available. The primary objectives of vulvar defect reconstruction are closure without any tension, less scarring of the perineum, and suturing of the donor area in a single stage. The secondary objectives include sensitive reconstruction and preservation of sexual function (4-7); however, these outcomes have some drawbacks. Defects of the groin, mons pubis, vagina, or urethra are frequently found during vulvar cancer surgery, and single-stage repair can cause deformity of the physiological structure in this area (which can affect the correct choice of flap for reconstruction). Local and pedicled flaps are appropriate choices for most wounds. Flap techniques can be technically demanding, but they are preferable in many cases owing to the minimal damage caused to the donor area, convenient cutting, and minimal technical difficulty. Other crucial considerations include possible previous radiotherapy and whether the inguinal lymph node has been cleaned. Therefore, after summarizing the examples of the repair of many cases of vulvar cancer by using the author’s technique, this paper puts forward the clinical process of "local flap, pedicled flap, and free flap" to be followed in the repair of wounds after vulvar cancer resection, as well as the general principles of different flaps required at different defect sites. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-1421/rc).

Methods

Ethical approval and Informed consent

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The protocol of the study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (No. SYSEC-KY-KS-2021-297). The requirement of obtaining informed consent was waived due to the retrospective and anonymous nature of the study.

Patients

An observational study was performed involving 26 patients with vulvar cancer who were admitted to Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital between February 2015 and February 2020 for surgical and reconstructive procedures. The clinical data of these 26 patients were analyzed. The average age of all patients was 54.5 years, which ranged from 28 to 73 years.

Eligibility criteria for patient inclusion

- Inclusion criteria: (i) patients diagnosed with vulvar cancer; (ii) patients undergoing primary surgery; (iii) patients who developed recurrence; and (iv) patients with inguinal node metastasis.

- Exclusion criteria: (i) patients with poor general condition combined with other serious systemic diseases; (ii) patients with other types of tumors; (iii) patients with mental diseases who could not cooperate in order to complete the treatment and follow-up; and (iv) patients lost to follow-up and lack of contact with the patients or their family members.

Surgical techniques

All patients underwent radical resection of vulvar cancer followed by post-surgical defect repair using random flap or axial flap transplantation (even for very complex defects).

Radical resection of vulvar cancer

The vulva, perineum, mons pubis, groins, vagina, and urethra were the most frequently resected structures, and the rectum, bladder, and lower abdominal wall were rarely included in resection. In 16 of the 26 cases, only extensive resection of the vulva was performed, and the remaining 10 cases were treated with extensive vulvar resection + unilateral or bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy.

Reconstruction of vulvar defects using flaps

Planned incisions for extirpative surgery were discussed preoperatively with the gynecologic oncologist to choose between the available reconstructive techniques. Flaps see the following case information for details. It is important to describe the assessment before surgery and the development of repairing protocol. All 26 patients underwent simultaneous reconstruction of the vulva. During surgery, the size and shape of the flap were adjusted according to the specific location of the defect. The donor area of the flap was sutured directly. Upon completion of ablative surgery, the defect was re-evaluated in the operating room.

Patient follow-up

Patient follow-up was carried out postoperatively every 50.4 months. Regular nuclear magnetic resonance examination was conducted to monitor for local recurrence and lymph node metastasis. Furthermore, positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) examination was performed to detect distant metastasis in patients with lymph node metastasis.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM, USA) and descriptive statistical data are presented as the mean ± SEM (standard deviation) or percentage.

Results

The tumor lesions of the 26 included patients differed in size, and some lesions were associated with different degrees of vaginal mucosal or urethral orificial involvement. There were 16 cases of primary surgery, seven cases of recurrence, and three cases of simple inguinal metastasis. Three cases had lesions in the pubic region, eight cases had unilateral lesions, 10 cases had bilateral lesions, and five cases had perianal tissue invasion. Also, 21 patients had squamous cell carcinoma, three patients had dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, one patient had adenoid cystic carcinoma, and one patient had sebaceous gland carcinoma. Three patients underwent cystostomy before surgery and Four patients underwent colostomy before surgery (Table 1).

Table 1

| Case | Age (years) | Operation time(hour) | Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Basic disease | Tumor size(cm) | Urethral orifice or the anal orifice is involved | Tumor dimension (cm) | Lymph gland | Clinical stages | Cystostomy or colostomy | Pathological type | Operation method | Flap dimension (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | 2.2 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | 2×2×1 | Urethral orifice is involved | 7×5 | No | Stage I | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Bilateral rhomboid flap | 7×5+7×5 |

| 2 | 51 | 3.2 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | 2×2×1 | Urethral orifice is involved | 4×3 | No | Stage I | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | VRAM flap | 4×3 |

| 3 | 73 | 4.1 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Hypertension | 7.5×6×3.5 | Urethral orifice is involved | 10×4.5 | ILND | Stage III | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 10×5 |

| 4 | 63 | 2.7 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Hyperthyroidism | 1.5×1.3×1.1 | Urethral orifice is involved | 5×4.5 | No | Stage II | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 6×5 |

| 5 | 66 | 1.9 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Hypertension and diabetes | 3×3×2 | the anal orifice is involved | 5×4 | ILND | Stage III | No | Sebaceous gland carcinoma | Bilateral V-Y flap | 5×4+5×4 |

| 6 | 65 | 2.3 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | 4.5×4.5×3.8 | Urethral orifice is involved | 7.5×6 | ILND | Stage II | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 8×6 |

| 7 | 51 | 2.4 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | 3×2.5×0.9 | No | 5×4 | No | Stage II | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 5×4 |

| 8 | 65 | 3.1 | Postoperative chemotherapy | Hypertension | 15×13×1 | Urethral orifice is involved | 18×16 | No | Stage III | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Medial femoral flap | Left 20×9 + right 25×8 |

| 9 | 58 | 2.7 | No | No | 12×8×2 | Urethral orifice and the anal orifice is involved | 15×13 | No | Stage II | Colostomy | Squamous cell carcinoma | Medial femoral flap | Left 30×9 + right 27×8 |

| 10 | 71 | 2.5 | No | Hypertension | 4×3×3 | No | 6×5 | ILND | Stage III | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 6×5 |

| 11 | 55 | 2.1 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Left lower extremity DVT | 13×12×4 | the anal orifice is involved | 14×14 | No | Stage II | Colostomy | Squamous cell carcinoma | Right medial femoral flap+ left anterolateral thigh flap | Left 17×7.5 + right 16×8 |

| 12 | 43 | 2.4 | Postoperative radiotherapy | No | 3×2×1 | No | 5.5×3 | ILND | Stage III | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 6×3.5 |

| 13 | 53 | 2.2 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | 25×9×6 | No | 26×10 | ILND | Stage IV | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Right VRAM flap + left anterolateral thigh flap | Left 7×6 + right 26×5 |

| 14 | 47 | 2.1 | Postoperative chemotherapy | Hypertension | 5×4×3 | the anal orifice is involved | 6×5 | No | Stage II | both | Squamous cell carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 6×5 |

| 15 | 63 | 2.3 | Postoperative chemotherapy | No | 12×6×1 | No | 14×8.5 | No | Stage III | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Medial femoral flap | 15×10 |

| 16 | 34 | 3.1 | No | No | 3×4×3 | No | 5×4 | No | Stage II | No | Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | Rhomboid flap | 5×4 |

| 17 | 63 | 3.3 | Postoperative chemotherapy | No | 3×3×2 | Urethral orifice is involved | 5×4 | No | Stage II | No | Adenoid cystic carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 5×4 |

| 18 | 40 | 3.4 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | 7×3.5×0.5 | No | 9×5 | No | Stage III | No | Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | Rhomboid flap | 10×5 |

| 19 | 28 | 2.6 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Mild anemia & second trimester | 6×3×2 | No | 7.2×5 | ILND | Stage IV | No | Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | Medial femoral flap | 7.5×5 |

| 20 | 61 | 3.1 | Postoperative chemotherapy | No | 12×12×2 | Urethral orifice is involved | 15×15 | No | Stage IV | Cystostomy | Squamous cell carcinoma | V-Y flap | Left 4×4 + right 15×15 |

| 21 | 30 | 3.2 | No | No | 2.1×2.4×0.5 | No | 4×4 | No | Stage II | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Rhomboid flap | 4×4 |

| 22 | 39 | 2.9 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | 4×2×1 | the anal orifice is involved | 5×3 | ILND | Stage III | Colostomy | Squamous cell carcinoma | Medial femoral flap | 5×3 |

| 23 | 55 | 3.1 | Postoperative radiotherapy | No | 13×11×3 | No | 14×13 | No | Stage III | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Medial femoral flap | 15×15 |

| 24 | 64 | 4.2 | Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Moderate anaemia | 14×9×1.5 | Urethral orifice is involved | 15×12 | ILND | Stage IV | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | V-Y flap | 15×12 |

| 25 | 72 | 1.9 | No | No | 3×1×0.5 | Urethral orifice is involved | 4.5×2.4 | ILND | Stage II | Cystostomy | Squamous cell carcinoma | Modified rhomboid flap | 5×3 |

| 26 | 54 | 2.1 | Preoperative chemotherapy | No | 8×5×1 | the anal orifice is involved | 10×7 | No | Stage III | No | Squamous cell carcinoma | Bilateral V-Y flap | 10×7+10×7 |

DVT, deep venous thrombosis; ILND, inguinal lymph node dissection; VRAM, vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous.

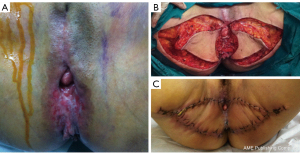

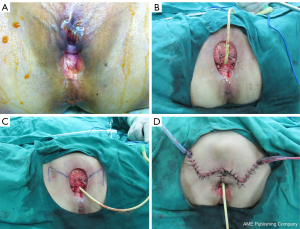

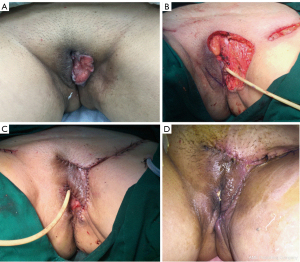

The skin defect size in the 26 included patients ranged from 4–26 cm × 2.4–16 cm, and the average defect size was 9.3×7 cm2. Also, a total of 38 flaps were used for transplantation and defect repair, and the area of the flap ranged from 4–30 cm × 3–15 cm. Further, 13 cases were treated with rhomboid flaps, four cases were treated with traditional fasciocutaneous V-Y (V-Y flap is a type of plastic surgery, and not an abbreviation) flaps, six cases were treated with medial femoral flaps, one case was treated with a vertical rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (VRAM) flap, and two cases were treated with combined flaps: one case was treated with combined VRAM and anterolateral thigh (ALT) flaps, and the other case was treated with combined medial femoral and ALT flaps (Table 2). Typical cases are shown in Figures 1-4 and Figures S1-S12.

Table 2

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD [range] | 54.5±12.7 [28–73] |

| Mean interval of disease before surgery | |

| Years, mean ± SD [range] | 4.2±1.9 [2–9] |

| Clinical stage, number (%) | |

| I | 2 (7.7) |

| II | 10 (38.5) |

| III | 10 (38.5) |

| IV | 4 (15.4) |

| Site, number (%) | |

| Perineum without | |

| Vagina/urethra/anus | 16 (61.5) |

| Perineum with anus | 5 (19.2) |

| Perineum with vagina | 8 (30.8) |

| Perineum with urethra | 2 (7.7) |

| Perineum and pubic mound | 10 (38.5) |

| Surgical techniques, number (%) | |

| Rhomboid flap | 13 (50.0) |

| V-Y flap | 4 (15.4) |

| Medial femoral flap | 6 (23.1) |

| VRAM flap | 1 (3.9) |

| Combined flap | 2 (7.7) |

| Follow up, months, mean ± SD [range] | 35.2±11.5 [15–50] |

VRAM, vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous.

The mean follow-up time ranged from 15 to 50 months. Excluding a patient treated with a single flap that developed partial necrosis in the distal portion and three patients with wound infection and dehiscence were treated with two-stage debridement and suturing. The remaining patients achieved good healing with one-stage treatment. In addition, one case developed anal stenosis, which was corrected by a two-stage local flap-plasty. Three patients experienced local tissue overstaffing; this outcome did not affect the functions of urination and defecation, and there was no pain or discomfort. The remaining patients were satisfied with the local appearance, local scars were not obvious, and there was no vaginal orificial, urethral orificial, or anal stenosis. Squamous cell carcinoma was the most commonly diagnosed cancer (80.8%). The procedures were performed to treat recurrent cancer in seven patients (26.9%). The overall survival rate was 76.9%. Rhomboid flaps were the most commonly used flaps for performing reconstruction in both the primary and recurrent groups.

Discussion

Vulvar carcinoma is a rare gynecological cancer that affects approximately 5% of women. The most common histotype is squamous cell carcinoma, which is caused by human papillomavirus in the majority of cases (1). Other histological types of tumors involving the vulvar region include melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, and verrucous carcinoma (8). The staging of vulvar cancer is determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (TNM) and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging systems (9).

Surgery is the primary treatment for vulvar cancer. Surgical treatment of malignant vulvar disease often requires resection of a large area of skin, and patients may experience significant morbidity if this area of skin is not replaced (10). Vulvar reconstruction is critical for cosmetic, functional, and psychological reasons. Reconstruction of oncological vulvar defects after ablation may be challenging due to the scarcity of local tissue, and should not impair important functions, including micturition, reproduction, and defecation (11).

Flap-based reconstruction is recommended for the treatment of vulvar cancer regardless of whether it is primary or recurrent and involves early or late large lesions. Enlarged resection for vulvar cancer results in skin and soft tissue defects of different sizes; although the majority of small lesions can be sutured directly, a certain amount of wound tension and excessive tension leads to delayed wound healing, cracking, and may even affect the blood supply to the skin (i.e., combined with the fact that the area is not clean). All of these factors affect wound healing. For mid-advanced lesions, the defect is larger and the wound cannot be directly sutured and closed. Further, it is not easy to fix the skin graft, graft survival is difficult, and some wounds exposing large blood vessels or the pubic bone require flap-based reconstruction. The wound healing ability following flap-based reconstruction is superior to that following direct suturing or skin grafting; our approach is conducive to systemic chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and radiotherapy as soon as possible after surgery, thereby reducing the chances of local tumor recurrence and distant metastasis. The majority of our 26 patients did not have any problem with the blood supply of the flap, which benefited from this surgical principle.

Reconstructive options include skin grafts, skin flaps, fasciocutaneous flaps, and myocutaneous flaps (5). Flap choice is mainly determined by the size and location of the defect (e.g., unilateral, bilateral, close to the pubic symphysis or anus, groin metastasis), the presence/absence of recurrent lesions and local lymph node dissection, and/or a history of local radiotherapy preoperatively. The vulva, perineum, mons pubis, groins, vagina, and urethra are the most frequently included structures in ablative surgery for vulvar cancer, while the rectum, bladder, and lower abdominal wall are rarely involved. The vulvoperineal area is not the only included region in vulvar cancer ablative surgery; close structures are also very frequently involved and a particular configuration of the defect is created by the combination of involved anatomical subunits (which always limits the indications of various flaps).

With respect to the defect repair method, we follow the principle of “local flap → pedicled flap → free flap”. Usually, skin grafting is not suitable due to the nature of the area and interference with its function and cosmesis. Flaps are invariably the best option for performing vulvoperineal reconstruction, and we propose using skin grafts only for skinning vulvectomy in Paget’s disease (where there is a thin defect and a high rate of relapse). Free flaps have been widely used for vulvoperineal reconstruction (4,5,12), but are not considered the first treatment option because of their complex management (13). Although these flaps, in combination, cover most dimensions of defects resulting from vulvar cancer resection, there are still some drawbacks, such as a difficult surgical procedure, significant damage to the donor area, and high technical requirements for the surgeon (5-7). For small- and medium-sized defects after vulvar cancer resection, a local flap should be used for repair. Local flaps have the following characteristics: simple operation, minimal trauma, short operative time, and similar thickness and texture between the flap and the defect area (which can produce a good postoperative appearance). Surgeons can choose the local flap according to the size and location of the defect, including rhomboid flaps, modified rhomboid flaps, rotation flaps, and V-Y advanced flaps. To repair small unilateral lesions, the flap from the labia minora can also be used. For treating a major defect of the labia majora, we recommend repair of the vulva and thigh root with a V-Y advancement flap or advanced flap. To repair the main defect of the pudendal area, we recommend using a rhomboid flap or advanced flap. To repair large metastatic lesions in the groin area, a local rhomboid flap (O-Z flap) can be used.

If the defect is large and affected by local lymphadenectomy (and there is a history of previous surgical incision or local radiotherapy), it is difficult to repair recurrent lesions with local flaps, and pedicled flaps can be considered. If necessary, kiss-flap technology or a combination of multiple flaps can be used to repair the defect and perform vulvoplasty. A Study have shown that the incidences of poor wound healing requiring debridement for perforator flaps and myocutaneous flaps are 22.4% and 25%, respectively (14). Compared to myocutaneous flaps, thinner perforator flaps are a better choice for treating some defects. According to the location and size of the defect, an iliac inguinal flap with superficial circumflex iliac artery, medial femoral flap, anterolateral femoral perforator flap, VRAM flap, or deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) flap can be selected. Owing to the many usable pedicled flaps around the vulva, the cost of a free flap is not high. In many patients with early-stage vulvar cancer, the external urethral opening and perianal skin are not invaded; thus, the external urethral opening and anus do not need to be repaired. However, in middle- and late-stage lesions, tumor invasion is relatively large and the lesions are relatively close to the urethral opening or the perianal skin, and can even violate and disrupt the urethral opening and perianal skin. In such cases, urethroplasty or anoplasty is often required. All relevant preoperative imaging examinations should be performed before surgery, especially PET-CT, to exclude distant metastasis and surgical contraindications. The MDT (Multi-Disciplinary Treatment) team, which comprises experts from the treating departments, including nutrition, imaging, pathology, blood transfusion, oncology, radiotherapy, biological, urology, anorectal surgery, ostomy, gynecologic oncology, plastic repair surgery, and other professionals (i.e., who conducted a full preoperative evaluation and discussion), should be consulted. Surgery is not recommended if the tumor cannot be completely removed due to locally advanced tumor invasion, or in cases where the patient cannot withstand or is not willing to undergo major surgery or has a poor quality of life and poor postoperative prognosis. It is necessary to formulate a comprehensive treatment and surgical plan for patients who have surgical indications. Long-term urethral stenosis or anal stenosis may occur because the epithelium around the urethral opening and the anus is brittle, the location is concealed, suturing is difficult, and there is a risk of delayed wound healing and splitting at the junction of the urethral opening or the anal preflap. In these cases, it is recommended to create a bladder fistula and simultaneously perform a colostomy for tumor resection and repair. For cases in which the tumor is large and ruptures before surgery (and affects the urination and defecation of patients), creating a bladder fistula and performing a colostomy can improve the local conditions and preoperative quality of life of patients. Also, given that the vulvar area is contaminated, preventive bladder fistula and colostomy are performed in the above cases. Postoperatively, an ostomy specialist is invited to care for the wound and fistula, which can be conducive to postoperative wound care and can reduce the incidence of wound infection. Early reduction of the occurrence of splitting and promotion of wound healing is beneficial for comprehensive treatment, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy (which can be performed early after surgery). The main limitations of this study include the small number of included cases, the exclusive use of observational methods, the inadequate follow-up time, and the lack of a comparative control group.

Conclusions

Expanding resection is an effective technique for the treatment of vulvar cancer, and postoperative surveillance is recommended to monitor for recurrence. Different skin flaps are effective premium options for postoperative defect reconstruction, and the selective use of skin flaps for treating vulvar defects preserves vulvar morphology and allows for relatively better functionality.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance in gynecologic surgery provided by the gynecologists.

Funding: This study was supported by the 5010 Research Project of Sun Yat-sen University (2019017).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-1421/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-1421/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-1421/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The protocol of the study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (No. SYSEC-KY-KS-2021-297). The requirement of obtaining informed consent was waived due to the retrospective and anonymous nature of the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Fin A, Rampino Cordaro E, Guarneri GF, et al. Experience with gluteal V-Y fasciocutaneous advancement flaps in vulvar reconstruction after oncological resection and a modification to the marking: Playing with tension lines. Int Wound J 2019;16:96-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tock S, Wallet J, Belhadia M, et al. Outcomes of the use of different vulvar flaps for reconstruction during surgery for vulvar cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:1625-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hollenbeck ST, Toranto JD, Taylor BJ, et al. Perineal and lower extremity reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;128:551e-63e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salgarello M, Farallo E, Barone-Adesi L, et al. Flap algorithm in vulvar reconstruction after radical, extensive vulvectomy. Ann Plast Surg 2005;54:184-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- John HE, Jessop ZM, Di Candia M, et al. An algorithmic approach to perineal reconstruction after cancer resection--experience from two international centers. Ann Plast Surg 2013;71:96-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong DS. Reconstruction of the perineum. Ann Plast Surg 2014;73:S74-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saleh DB, Liddington MI, Loughenbury P, et al. Reconstruction of the irradiated perineum following extended abdomino-perineal excision for cancer: an algorithmic approach. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2012;65:1537-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koh WJ, Greer BE, Abu-Rustum NR, et al. Vulvar Cancer, Version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017;15:92-120. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;105:103-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weikel W, Schmidt M, Steiner E, et al. Reconstructive plastic surgery in the treatment of vulvar carcinomas. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;136:102-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Benna S, Tzakas E. Postablative reconstruction of vulvar defects with local fasciocutaneous flaps and superficial fascial system repair. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;286:443-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Negosanti L, Sgarzani R, Fabbri E, et al. Vulvar Reconstruction by Perforator Flaps: Algorithm for Flap Choice Based on the Topography of the Defect. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2015;25:1322-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lazzaro L, Guarneri GF, Rampino Cordaro E, et al. Vulvar reconstruction using a "V-Y" fascio-cutaneous gluteal flap: a valid reconstructive alternative in post-oncological loss of substance. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2010;282:521-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elia J, Do NTK, Chang TN, et al. Redefining the Reconstructive Ladder in Vulvoperineal Reconstruction: The Role of Pedicled Perforator Flaps. J Reconstr Microsurg 2022;38:10-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: A. Kassem)