Comparison of mediastinal and non-mediastinal neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma associated with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumors occurring in children. The median age at diagnosis is 16 months, and 95% of cases are diagnosed before 7 years of age (1). The neoplasm grows from progenitor cells of the sympathetic nervous system and can be detected anywhere along the sympathetic neurological circuit: retroperitoneally (65%), in the adrenal glands (40%), mediastinally (15%), cervically (11%), and pelvically (3%) (2). Children with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome (OMS) are typically presented with acute or subacute ataxia between 6 and 36 months of age and they are unable to walk and/or sit (3). This is accompanied by severe irritability and opsoclonus which appears at variable times from the initial onset to as late as a few weeks after the onset of the motor symptoms (4). In 1968, Dyken and Kolar described the association of OMS with occult neuroblastoma (5). An association between solid neuroblastoma and OMS was actually first described in a paper by Cushing et al. on the spontaneous transformation of neuroblastoma to ganglioneuroma in 1927—a fact that is only appreciated recently (6). OMS occurs in 2–3% of patients with neuroblastoma (7), but neuroblastoma is found in as many as 50% of children who are diagnosed with OMS (8). The percentage of mediastinal localization of the tumor (49%) is much higher compared with neuroblastomas without OMS (9). This review compared the different localization of the tumor in order to identify and characterize features of the OMS syndrome and treatments between mediastinal and non-mediastinal neuroblastoma associated with OMS. We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-1120/rc) (10).

Methods

Standard systematic review methodology was employed. A systematic review of case reports and case series published in PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, Embase and Cochrane. The search has no limit on date with the last search done on Dec 31, 2020. There is no publication restrictions or study design filters applied in the search. The search strategy for those databases was as follows: (neuroblastoma [all fields]) AND (opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome [all fields]). A hand search was performed in all five databases.

Inclusion criteria included well-described OMS with exact tumor location, treatments and outcome. As OMS with neuroblastoma is rare, all the cases are included in case reports.

The results for each group are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (). The log-rank was observed minus expected (o–e) statistics, one from each trial, and their variances (v), were summed to produce, respectively, a grand total was observed minus expected (G) and its variance (V). The one-step estimate of the log of the event rate ratio is G/V. The χ² test statistic (χ²n–1) for heterogeneity between n trials is S–(G²/V), where S is the sum over all the trials of (o–e)²/v. Heterogeneity of rate ratios among multiple subgroups was defined by baseline characteristics and was investigated by a global heterogeneity test, which helped to avoid misinterpreting false positive results arising from multiple comparisons.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted by STATA version 12.0. Relative risk (RR) was applied for dichotomous variables. The I2 statistic was used to test the degrees of heterogeneity, the P value of I2<0.05 was used to indicate high heterogeneity. The random-effects model was applied to pool the high heterogeneity results and a fixed-effects model was used for low heterogeneity (P value of I2 >0.05). P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

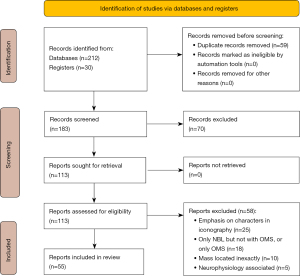

Two hundred and forty-two papers were identified including the hand search yielding 30 papers. Fifty-nine papers were duplicate papers from different search engines, 70 papers were excluded after title and abstract evaluation, and 58 papers were excluded after full-text review because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Among the 55 papers included, some were case series with multiple cases, and the total number of cases analyzed was 77.

Children with OMS and neuroblastoma

We focused on gender, age of onset, tumor location, pathology, neurological symptoms, treatments and prognosis in the 77 children identified through our search, these clinical and biological characteristics were listed in chronological order and was displayed in Table 1. The tumor location included mainly the abdomen and the mediastinum. Tumors on the neck and the pelvic area were rare. Neurological symptoms identified from the 77 cases were mainly from these four aspects: ataxia, opsoclonus, myoclonus, and irritability. The other clinical symptoms included neonatal lupus, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), constipation and etcetera. Biopsy or resection, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and treatments of OMS were also included in the treatments. Tumor prognosis was reported as recurrence and non-recurrence, and the prognosis of neurological symptoms was mainly divided into three categories: no symptom, improved symptom, and persistent symptom. No symptom is defined as positive response to treatments of OMS; improved symptom is defined as patients showed benefits from the treatment but OMS is not in complete remission; persist symptom is identified as no response to treatment. The average age at diagnosis for the 77 cases with known age was 21.3±11.8 months; they consisted of thirty-two males and forty-five females. The tumors were located in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, neck, and pelvic, it accounted for 36% (n=28), 55% (n=42), 4% (n=3) and 5% (n=4) of all the cases, respectively. See Table 1 for the detailed information with all reported cases (n=77) that met the inclusion criteria.

Table 1

| Author | Sex | Age of onset | Location of tumor | Pathology | Neurologic symptom | Treatments | Outcome (symptom & tumor) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shtarbanov et al., 2020 (11) | F | 21m | T1-3, posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonusa | Surgery; chemotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| F | 21m | The left carotid space | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy | No symptom remission & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| F | 18m | Retroperitoneum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Kaur et al., 2019 (12) | M | 24m | Left posterior mediastinum | Not reportedb | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Without surgery | Not reported |

| Storz et al., 2019 (13) | F | 7m | Left posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.Oa | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| M | 13m | The left adrenal gland | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| M | 13yr11m | T11-L1, the right paravertebral | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Greensher et al., 2018 (14) | M | 14m | Abdomen | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Biopsy; chemotherapy; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Sharawat et al., 2018 (15) | M | 15m | T10-L2, vertebrae | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability (neonatal lupus) | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Johnston et al., 2018 (16) | M | 10m | (INSS IVs) the neck | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| F | 21m | (INSS I) the left suprarenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Mizuno et al., 2017 (17) | F | 14m | The right adrenal gland | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; (laryngeal stridor) | Biopsy; chemotherapy | Symptom improved & tumor remain |

| Wu et al., 2017 (18) | F | 16m | The retroperitoneal area | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Meena et al., 2016 (19) | M | 26m | T6-8 right posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| F | 34m | T6-8, left posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Without surgery | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| M | 22m | Abdomen | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| F | 34m | L2-3, left upper psoas muscle extending into left neural foramen | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| M | 36m | Abdomen | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | Persistent symptom & died of febrile encephalopathy (not related to disease) | |

| F | 34m | Abdomen | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | T.O | No symptom & tumor recurrence 2 years later | |

| Ghia et al., 2016 (20) | F | 17m | T3-8, right posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability; (T1DM) | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Sweeney et al., 2016 (21) | F | 11yr | L2-4, vertebral levels | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonusa | Biopsy; chemotherapy; T.O | Persistent symptom & tumor remain |

| Toyoshima et al., 2016 (22) | M | 2yr | The left adrenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Amini et al., 2016 (23) | F | 6yr | (INSS IV) para-aortic, abdomen | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; Opsoclonus; myoclonus; (constipation) | Surgery; radiotherapy; T.O | Persistent symptom & tumor recurrence |

| Galgano et al., 2015 (24) | F | 21m | The pancreatic body | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonusa; myoclonus | Biopsy; chemotherapy | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Hu et al., 2015 (25) | M | 5m | The left adrenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; chemotherapy | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Sinha et al., 2014 (26) | F | 1yr6m | (INSS IIa) T10-L1, the right para-spinal | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Krivochenitser et al., 2014 (27) | F | 2yr | The right suprarenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Maranhão et al., 2013 (28) | F | 17m | T3-6, right posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Joshi et al., 2013 (29) | M | 0.5m | T3-5, posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonusa; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| M | 26m | (INSS IV) T1-4, posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Biopsy; chemotherapy | Symptom improved & tumor remain | |

| Morales La Madrid et al., 2012 (30) | F | 14m | (INSS I) pelvic | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; (constipation) | Surgery; T.O | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Oguma et al., 2012 (31) | M | 11m | (INSS I) retroperitoneal | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Kuyama et al., 2012 (32) | F | 4y4m | The right adrenal gland | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Pranzatelli et al., 2012 (33) | M | 22m | The hilus of the right kidney | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; T.O | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Paliwal et al., 2010 (34) | M | 8m | (INSS IIa) retroperitoneal pelvic | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & tumor recurrence |

| Corapcioglu et al., 2008 (35) | M | 48m | right posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Stefanowicz et al., 2008 (36) | F | 15m | The right suprarenal gland | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| F | 16m | The retroperitoneal area | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; chemotherapy | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| M | 4yr | The right suprarenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| F | 3.5yr | The right suprarenal gland | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Burke et al., 2008 (37) | M | 3yr6m | Above the right kidney | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Bell et al., 2008 (38) | F | 19m | The right renal hilum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Ertle et al., 2008 (39) | M | 33m | (INSS III) T10-L1, the right para-spinal | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Badaki et al., 2007 (40) | F | 15m | The right presacral | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery | Loss of follow-up |

| Cardesa-Salzmann et al., 2006 (41) | F | 20m | (INSS I) right posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus (EBV+) | Surgery | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Chang et al., 2006 (42) | M | 4yr | The left adrenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Armstrong et al., 2005 (43) | M | 14m | (INSS II) posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; Opsoclonus; Myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Gesundheit et al., 2004 (44) | F | 19m | The right adrenal gland | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability; (VIP associated diarrhea) | Surgery | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Emir et al., 2003 (45) | M | 12m | (INSS IIb) the left suprarenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Swart et al., 2002 (46) | F | 13m | Supraphrenic lesion | Not reportedb | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Without surgery; radiotherapy; T.O | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Maeoka et al., 1998 (47) | F | 13m | Posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritabilitya | Surgery | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Veneselli et al., 1998 (48) | M | 8m | (INSS III) retroperitoneal | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Posada et al., 1998 (49) | F | 12m | The level of C7 | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Janss et al., 1996 (50) | M | 29m | The left suprarenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; T.O | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| F | 21m | The celiac axis | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Fisher et al., 1994 (51) | F | 20m | The left adrenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Mitchell et al., 1990 (52) | M | 14m | Left posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| F | 3yr | The left suprarenal gland | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| F | 13m | The vena cava into the right pelvis | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; chemotherapy | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| F | 15m | The hilus of the left kidney | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonusa | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| F | 15m | The left periaortic | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Harel et al., 1987 (53) | F | 1yr | L2-3, palpable left to the midline | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus (hypertension) | Surgery; chemotherapy; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Kinast et al., 1980 (54) | F | 9m | Retroperitoneal | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; T.O | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Malmström Groth et al., 1972 (55) | F | 20m | (INSS I) right posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Leonidas et al., 1972 (56) | F | 14m | (INSS II) right posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Martin et al., 1971 (57) | F | 8m | Posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Chemotherapy; radiotherapy | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Förster et al., 1971 (58) | F | 21m | (INSS I) posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | No symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Moe et al., 1970 (59) | F | 13m | (INSS II) right posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| M | 24m | (INSS II) left posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Bray et al., 1969 (60) | M | 23m | (INSS IV) posterior mediastinum | Ganglioneuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonusa; irritability | Biopsy; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & died of tumor |

| M | 13m | Left posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonusa; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | Persistent symptom & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Brissaud et al., 1969 (61) | F | 27m | (INSS I) posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Lemerle et al., 1969 (62) | M | 15m | (INSS IV) posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & tumor recurrence |

| F | 37m | Posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus | Surgery; chemotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence | |

| Dyken et al., 1968 (5) | F | 8m | (INSS II) posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonusa; irritability | Surgery; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Solomon et al., 1968 (63) | M | 13m | (INSS II) left posterior mediastinum | Neuroblastoma | Ataxiaa; opsoclonus; myoclonusa; irritability | Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

| Davidson et al., 1968 (64) | M | 13m | The right lower quadrant of the abdomen | Neuroblastoma | Ataxia; opsoclonus; myoclonus; irritability | Surgery; radiotherapy | Symptom improved & no evidence of tumor recurrence |

a, unitary first symptom of OMS; b, MRI scan revealed a supraphrenic, paravertebral tumor on the left side most likely resembling a neuroblastoma or ganglioneuroma; c, treatments of OMS are about ACTH and oral corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, rituximab, plasmapheresis, et al. OMS, opsoclonus–myoclonus syndrome; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; M, male; F, female; m, months; yr, years; T.O, treatments of OMSc; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; EBV, epstein-barr virus; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide.

Comparisons of children with OMS and neuroblastoma in different locations

Table 2 summarizes the syndromes with all the reported cases (n=77) that met the inclusion criteria: mediastinal neuroblastoma (n=28), non-mediastinal neuroblastoma (n=49).

Table 2

| Characteristics | Mediastinal neuroblastoma (28 cases) | Non-mediastinal neuroblastoma (49 cases) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12/42.9 | 20/40.8 |

| Female | 16/57.1 | 29/59.2 |

| Age at time of neurologic dysfunction (months), mean ± SD | 18.4±7.3 | 23.1±13.4 |

| Unitary first symptom of OMS | ||

| Ataxia | 6/21.4 | 8/16.3 |

| Irritability | 1/3.6 | 0/0 |

| Myoclonus | 5/18 | 2/4.1 |

| Opsoclonus | 1/3.6 | 1/2 |

| None unitary first symptom of OMS | 15/53.4 | 38/77.6 |

| Surgical treatments | ||

| B+C or/and R | 2/7.2 | 5/10.2 |

| S | 9/32.1 | 27/55.1 |

| S+C or/and R | 13/46.3 | 17/34.7 |

| WS | 2/7.2 | 0/0 |

| WS+C or/and R | 2/7.2 | 0/0 |

| Management associateda | ||

| Treatments of OMS | 8/28.6 | 34/69.4 |

| None | 20/71.4 | 15/30.6 |

| Neurologic symptoms | ||

| No symptom | 9/32.1 | 13/26.5 |

| Symptom improved | 15/53.4 | 18/36.7 |

| Persistent symptom | 3/10.9 | 17/34.8 |

| Loss of follow-up | 1/3.6 | 1/2 |

| Tumor outcome | ||

| Reoccur or death | 3/10.9 | 4/8.2 |

| Stable disease | 24/85.5 | 44/89.8 |

| Loss of follow-up | 1/3.6 | 1/2 |

| Pathologic examination | ||

| Ganglioneuroblastoma | 9/32.1 | 18/36.7 |

| Neuroblastoma | 17/60.7 | 31/63.3 |

| WS | 2/7.2 | 0/0 |

| Concomitant symptom | ||

| Hypertension | 1/3.6 | 1/2 |

| Constipation | 0/0 | 2/4.1 |

| Laryngeal stridor | 1/3.6 | 1/2 |

| Neonatal lupus | 26/92.8 | 1/2 |

| VIP associated diarrhea | 1/2 | |

| Not reported | 43/87.9 |

a, management associated is about treatments of OMS, such as ACTH and oral corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, rituximab, plasmapheresis, et al. OMS, opsoclonus–myoclonus syndrome; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; B, biopsy; S, surgery; WS, without surgery; C, chemotherapy; R, radiotherapy; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; EBV+, Epstein-Barr virus positive; VIP, Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide.

Characters in mediastinal and non-mediastinal neuroblastoma—subgroup analyses

There were no significant differences in overall characters in mediastinal neuroblastoma and non-mediastinal neuroblastoma trials [rate ratio (RR) 1.07 (95% CI: 0.85–1.33), P=0.573; Figure 2] such as: sex [RR 0.99 (95% CI: 0.72–1.37), P=0.970; Figure 2], unitary first symptom of OMS [RR 1.92 (95% CI: 0.90–4.09), P=0.092; Figure 2], surgical treatments [RR 1.09 (95% CI: 0.52–2.28), P=0.814; Figure 2], treatments of OMS [RR 0.99 (95% CI: 0.77–5.65), P=0.991; Figure 2], neurologic symptoms [RR 0.99 (95% CI: 0.50–1.99), P=0.986; Figure 2], tumor outcome [RR 0.96 (95% CI: 0.81–1.15), P=0.664; Figure 2] and pathology [RR 0.97 (95% CI: 0.67–1.39), P=0.854; Figure 2]. However, data from trials showed that cases with mediastinal neuroblastoma seemed to receive less treatments of OMS [RR 0.41 (95% CI: 0.22–0.76); Figure 2] and resulted in decreased persistent neurologic symptoms [RR 0.31 (95% CI: 0.10–0.96); Figure 2], which means more cases were in remission.

Discussion

Overall, we found 77 cases of children with neuroblastoma and OMS from literature review. While OMS occurs in 2–3% of patients with neuroblastoma (7), many of these syndromes are rare and most of the cases were case reports. Because the data was obtained through a systematic literature review, the available data in each case report was limited, therefore randomized controlled test was not performed. In Altman and Baehner’s study (65), the case reports of 28 neuroblastoma patients who had opso-myoclonus as their presenting feature were reviewed. In comparison to the 30–34% two-year survival rate for the overall population of patients with neuroblastoma, those exhibiting the opso-myoclonus and neuroblastoma combination had a higher tumor-free two-year survival rate of 89.3%. This may be due to the fact that OMS and neuroblastoma were autoimmune in nature which affected the growth and the spread of the tumor.

The average age of those children with OMS in the mediastinal neuroblastoma group and non-mediastinal neuroblastoma group is older than the median age of children with neuroblastoma reported in the literature (1). In our review, most of the cases in the mediastinal neuroblastoma group were reported as stage I-II, while the stages of the tumor in the non-mediastinal group were mostly unknown. The 5-year survival rate of the mediastinal neuroblastoma cases was significantly more favorable than that of the non-mediastinal neuroblastomas. The majority of mediastinal neuroblastoma cases presented at an early stage are associated with favorable prognostic factors (66). We found that the average age between the mediastinal and non-mediastinal neuroblastoma groups had no significant difference (P>0.05). Because of the earlier diagnosis and distinct biological characteristics, a favorable prognosis would suggest less aggressive treatment is needed for these patients (67). The median age and average age of the two groups are both older than one year of age, with only 10 children out of 77 (13%) cases were younger than one year old. Children within one year of age have relatively under-developed autoimmunity, which may be correlated with the lower occurrence of OMS in children of this age (65,68). There are slightly more female children in the mediastinal and non-mediastinal group than males, this is consistent with the reported children who suffer from neuroblastoma but without OMS (66,67,69). Children with OMS are usually presented as a typical OMS, or unitary first symptom such as acute/subacute ataxia (unable to walk and/or sit) (3), this is accounted for 21.4% in the mediastinal group and 16.3% in the non-mediastinal group. Nearly half of the children with mediastinal neuroblastoma and OMS started with a unitary neurological symptom and were then accompanied with severe irritability and opso-myoclonus at later time (46.6%). The guidelines for the treatment of the neuroblastoma do not differ according to the localization of the tumor, from the literature there is no significant difference in the two groups with regards to surgical treatments, radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the literature [RR 1.09 (95% CI: 0.52–2.28), P=0.814; Figure 2], and the pathology [RR 0.97 (95% CI: 0.67–1.39), P=0.854; Figure 2], and no clear reduction in rates of recurrence (or death) of the tumor [RR 0.96 (95% CI: 0.81–1.15), P=0.664; Figure 2]. There is no significant difference in recurrence or death and the survival rate is low. However, the mediastinum group with localized tumor (stage I, II, and III) may be associated with more favorable clinical and biological characteristics and has better outcome (70): the survival rate of the mediastinum group with localized tumor is 100%. The interesting point is, in cases that underwent an incomplete resection of the primary tumors in localized neuroblastoma, the 5-year survival rate of the mediastinal neuroblastoma cases was significantly more favorable than that of the other neuroblastomas (66). Furthermore, we found that only four children in the mediastinal group did not have surgery. Among them, one was lost in follow-up; two of the remaining three cases received only radiotherapy and chemotherapy and the last one did not receive any treatment but was on observation and the tumor and OMS disappeared completely. This is in line with Brodeur GM’s theory of “spontaneous regression” by an “anti-tumor immune response”. He argued that all children with OMS should have had neuroblastoma, but less than half of the children with OMS were found to have solid tumor due to the spontaneous regression, which was called autoimmunity caused by the existence of the tumor. Brodeur GM reviewed several possible mechanisms of the spontaneous regression of neuroblastoma: (I) neurotrophin deficiency: alterations of TrkA neurotrophin receptor dependence or lack of nerve growth factor (NGF) in the microenvironment; (II) loss of telomerase activity or shortening of telomere; (III) tumor destruction mediated by anti-tumor immune responses in humoral or cellular immunity; (IV) alterations in epigenetic regulation and other possible mechanisms: Changes in gene methylation or histone modifications (71).

Although treatments of OMS in postoperative cases of the mediastinal group are significantly less than those in the non-mediastinal group [RR 0.41 (95% CI: 0.22–0.76); Figure 2], the cases of persistent symptom of OMS in the non-mediastinal group are significantly higher than that in the mediastinal group [RR 0.31 (95% CI: 0.10–0.96); Figure 2], which means the number of positive response cases (including complete response and partial response) of neurological symptoms in the mediastinal group is significantly higher than in the non-mediastinal group. Therefore, it may be determined that OMS in mediastinal neuroblastoma is more likely to resolve with the treatment of the primary tumor rather than treating OMS alone.

The pathogenesis of the OMS in neuroblastoma is mainly considered as paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS). It may be due to a paraneoplastic or autoimmune etiology when it is associated with neuroblastoma (72), meaning there may be the presence of an antineuronal antibody cross-reacting with areas of the patient's tumor (51). Various studies have shown that the different antigen-antibody reactions produced by various tumors are closely related to the manifestations of neurological symptoms: Purkinje Cell Antibody (PCA) leads to cerebellar ataxia (73,74), while anti-neuronal nuclear antibody (ANNA) leads to encephalomyelitis and peripheral nervous system disorders (75-80). ANNA-1 and ANNA-2 differ in protein molecular weights (76). ANNA-1 (also known as anti-Hu) is a marker of paraneoplastic autoimmunity associated with small-cell carcinoma (usually of the lung) and peripheral nervous system presentations are most common; ANNA-2 IgG (also known as anti-Ri) is found in patients with small-cell lung carcinoma or breast carcinoma and bind to the central nervous system (76-80). Among all the complications, there were only two cases with constipation in the non-mediastinal neuroblastoma which was associated with the disease itself, and the serum ANNA-1 of the children with constipation was positive (23,30). In some cases, having positive anti-Hu antibody can lead to intestinal dysfunction in children with neuroblastoma, such as constipation, gut dysmotility and even paralytic ileus (23,30,81-83), and is collectively called gastro-intestinal anti-Hu syndrome. It may be because Anti-Hu antibodies has evoked neuronal apoptosis which contributes to the enteric nervous system impairment leading to underlying paraneoplastic gut dysmotility (84), but the incidence rate is only 2 out of 77 cases in our study (2.6%). Despite the fact that anti-Hu antibodies are present in several other presumably paraneoplastic conditions occasionally seen in children with neuroblastoma, no antibody has been identified as etiologic in OMS, even after a great deal of searching by multiple labs.

There are several limitations in this review. Not all case reports were complete with all of the variables of interest: such as the stages of the tumor, MYCN status, tumor location, pathology and survival status. Since cases are rare, we have to include older cases and some cases that were lost in follow-up in the later part of the study period. Due to the various follow-up time, we were unable to produce a survival curve.

In summary, OMS may be possibly associated with the progression of mediastinal and non-mediastinal neuroblastoma (7,71,85-87). We also noted that mediastinal neuroblastoma has a better prognosis than non-mediastinal neuroblastoma in terms of tumor treatments and neurological symptoms.

Conclusions

Mediastinal neuroblastoma with OMS, one of the common types of neurogenic tumors with OMS in children (9), is more likely to present with a single neurological symptom at first, which might be associated with more favorable clinical and biological characteristics and a better outcome than non-mediastinal neuroblastoma. OMS in mediastinal neuroblastoma might also be resolved significantly through resection of the tumor followed by appropriate radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and no long-term treatments of OMS is needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laura Ng, RN (Registered Nurse, British Columbia, Canada), BSN (Bachelor in Science of Nursing, University of British Columbia, Canada), CDE (Certified Diabetes Educator, Canada) and Helen Zheng, RN (Registered Nurse, British Columbia, Canada) for paper editing.

Funding: This study received financial support from

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-1120/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-1120/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-1120/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Brisse HJ, McCarville MB, Granata C, et al. Guidelines for imaging and staging of neuroblastic tumors: consensus report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Project. Radiology 2011;261:243-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ozerov SS, Samarin AE, Andreev ES, et al. Neurosurgical aspects of the treatment of neuroblastoma patients. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko 2016;80:50-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell WG, Davalos-Gonzalez Y, Brumm VL, et al. Opsoclonus-ataxia caused by childhood neuroblastoma: developmental and neurologic sequelae. Pediatrics 2002;109:86-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bataller L, Graus F, Saiz A, et al. Clinical outcome in adult onset idiopathic or paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus. Brain 2001;124:437-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dyken P, Kolár O. Dancing eyes, dancing feet: infantile polymyoclonia. Brain 1968;91:305-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cushing H, Wolbach SB. The Transformation of a Malignant Paravertebral Sympathicoblastoma into a Benign Ganglioneuroma. Am J Pathol 1927;3:203-216.7.

- Rudnick E, Khakoo Y, Antunes NL, et al. Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome in neuroblastoma: clinical outcome and antineuronal antibodies-a report from the Children's Cancer Group Study. Med Pediatr Oncol 2001;36:612-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tate ED, Allison TJ, Pranzatelli MR, et al. Neuroepidemiologic trends in 105 US cases of pediatric opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2005;22:8-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boltshauser E, Deonna T, Hirt HR. Myoclonic encephalopathy of infants or "dancing eyes syndrome". Report of 7 cases with long-term follow-up and review of the literature (cases with and without neuroblastoma). Helv Paediatr Acta 1979;34:119-33. [PubMed]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372: [PubMed]

- Shtarbanov IA, Boronsuzov IK, Chakarov IR, et al. Therapeutic results in three cases of ganglioneuroblastoma associated with opsoclonus myoclonus ataxia syndrome. Indian J Cancer 2020;57:216-8. [PubMed]

- Kaur A, Bhagwat C, Madaan P, et al. Dancing Eyes. J Pediatr 2019;214:231. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Storz C, Bares R, Ebinger M, et al. Diagnostic value of whole-body MRI in Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome: a clinical case series (3 case reports). BMC Med Imaging 2019;19:70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greensher JE, Louie J, Fish JD. Therapeutic plasma exchange for a case of refractory opsoclonus myoclonus ataxia syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharawat IK, Saini AG, Kasinathan A, et al. Neuroblastoma, opsoclonus-myoclonus ataxia syndrome and neonatal lupus with congenital heart block: is there an association? Lupus 2018;27:2298-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnston DL, Murray S, Irwin MS, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for refractory opsoclonus myoclonus ataxia syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018;65:e27110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mizuno T, Kumada S, Naito R. Sleep-Related Laryngeal Stridor in Opsoclonus Myoclonus Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 2017;77:91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu H, Mody AP. A Toddler With Uncontrollable Shaking After a Minor Fall. Pediatr Emerg Care 2017;33:e95-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meena JP, Seth R, Chakrabarty B, et al. Neuroblastoma presenting as opsoclonus-myoclonus: A series of six cases and review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci 2016;11:373-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghia T, Kanhangad M, Alessandri AJ, et al. Opsoclonus-Myoclonus Syndrome, Neuroblastoma, and Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus in a Child: A Unique Patient. Pediatr Neurol 2016;55:68-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sweeney M, Sweney M, Soldán MM, et al. Antineuronal Nuclear Autoantibody Type 1/Anti-Hu-Associated Opsoclonus Myoclonus and Epilepsia Partialis Continua: Case Report and Literature Review. Pediatr Neurol 2016;65:86-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toyoshima D, Morisada N, Takami Y, et al. Rituximab treatment for relapsed opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Brain Dev 2016;38:346-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amini A, Lang B, Heaney D, et al. Multiple sequential antibody-associated syndromes with a recurrent mutated neuroblastoma. Neurology 2016;87:634-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galgano S, Royal S. Primary pancreatic neuroblastoma presenting with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Radiol Case Rep 2015;11:36-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu LY, Shi XY, Feng C, et al. An 8-year old boy with continuous spikes and waves during slow sleep presenting with positive onconeuronal antibodies. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2015;19:257-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sinha S, Sarin YK. Rituximab for opsoclonus myoclonus ataxia syndrome associated with neuroblastoma. Indian J Pediatr 2014;81:218-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krivochenitser R, Lemma Y, Wynn B, et al. Ophthalmic presentation in the emergency department: a case report of a girl with "shimmering eyes". J Emerg Med 2014;46:e163-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maranhão MV, de Holanda AC, Tavares FL. Kinsbourne syndrome: case report. Braz J Anesthesiol 2013;63:287-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joshi P, Lele V. Somatostatin receptor positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) in the evaluation of opsoclonus-myoclonus ataxia syndrome. Indian J Nucl Med 2013;28:108-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morales La Madrid A, Rubin CM, Kohrman M, et al. Opsoclonus-myoclonus and anti-Hu positive limbic encephalitis in a patient with neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;58:472-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oguma M, Morimoto A, Takada A, et al. Another promising treatment option for neuroblastoma-associated opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome by oral high-dose dexamethasone pulse: lymphocyte markers as disease activity. Brain Dev 2012;34:251-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuyama H, Nii A, Takehara H, et al. Ganglioneuroblastoma, intermixed with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Pediatr Int 2012;54:e26-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pranzatelli MR, Tate ED, Shenoy S, et al. Ofatumumab for a rituximab-allergic child with chronic-relapsing paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;58:988-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paliwal VK, Chandra S, Verma R, et al. Clonazepam responsive opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome: additional evidence in favour of fastigial nucleus disinhibition hypothesis? J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2010;117:613-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corapcioglu F, Mutlu H, Kara B, et al. Response to rituximab and prednisolone for opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome in a child with ganglioneuroblastoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2008;25:756-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stefanowicz J, Izycka-Swieszewska E, Drozyńska E, et al. Neuroblastoma and opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome--clinical and pathological characteristics. Folia Neuropathol 2008;46:176-85. [PubMed]

- Burke MJ, Cohn SL. Rituximab for treatment of opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome in neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;50:679-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bell J, Moran C, Blatt J. Response to rituximab in a child with neuroblastoma and opsoclonus-myoclonus. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;50:370-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ertle F, Behnisch W, Al Mulla NA, et al. Treatment of neuroblastoma-related opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome with high-dose dexamethasone pulses. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;50:683-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Badaki OB, Schapiro ES. Dancing eyes, dancing feet: opsoclonus-myoclonus in an 18-month-old child with neuroblastoma. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007;23:885-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardesa-Salzmann TM, Mora J, García Cazorla MA, et al. Epstein-Barr virus related opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia does not rule out the presence of occult neuroblastic tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2006;47:964-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang BH, Koch T, Hopkins K, et al. Neuroblastoma found in a 4-year-old after rituximab therapy for opsoclonus-myoclonus. Pediatr Neurol 2006;35:213-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armstrong MB, Robertson PL, Castle VP. Delayed, recurrent opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome responding to plasmapheresis. Pediatr Neurol 2005;33:365-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gesundheit B, Smith CR, Gerstle JT, et al. Ataxia and secretory diarrhea: two unusual paraneoplastic syndromes occurring concurrently in the same patient with ganglioneuroblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2004;26:549-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Emir S, Akyüz C, Büyükpamukçu M. Correspondence: treatment of the neuroblastoma-associated opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia (OMA) syndrome with high-dose methylprednisolone. Med Pediatr Oncol 2003;40:139. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swart JF, de Kraker J, van der Lely N. Metaiodobenzylguanidine total-body scintigraphy required for revealing occult neuroblastoma in opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Eur J Pediatr 2002;161:255-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maeoka Y, Maegaki Y. Hyperexcitability of the blink reflex in a child with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. No To Hattatsu 1998;30:323-7. [PubMed]

- Veneselli E, Conte M, Biancheri R, et al. Effect of steroid and high-dose immunoglobulin therapy on opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome occurring in neuroblastoma. Med Pediatr Oncol 1998;30:15-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Posada JC, Tardo C. Neuroblastoma detected by somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in a case of opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome. J Child Neurol 1998;13:345-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janss A, Sladky J, Chatten J, et al. Opsoclonus/myoclonus: paraneoplastic syndrome of neuroblastoma. Med Pediatr Oncol 1996;26:272-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fisher PG, Wechsler DS, Singer HS. Anti-Hu antibody in a neuroblastoma-associated paraneoplastic syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 1994;10:309-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell WG, Snodgrass SR. Opsoclonus-ataxia due to childhood neural crest tumors: a chronic neurologic syndrome. J Child Neurol 1990;5:153-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harel S, Yurgenson U, Rechavi G, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and opsoclonus as the initial manifestations of myoclonic encephalopathy associated with neuroblastoma. Childs Nerv Syst 1987;3:245-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kinast M, Levin HS, Rothner AD, et al. Cerebellar ataxia, opsoclonus, and occult neural crest tumor. Abdominal computerized tomography in diagnosis. Am J Dis Child 1980;134:1057-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malmström-Groth A. Cerebellar encephalopathy and neuroblastoma. Eur Neurol 1972;7:95-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leonidas JC, Brill CB, Aron AM. Neuroblastoma presenting with myoclonic encephalopathy. Radiology 1972;102:87-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin ES, Griffith JF. Myoclonic encephalopathy and neuroblastoma. Report of a case with apparent recovery. Am J Dis Child 1971;122:257-8. [PubMed]

- Förster C, Weinmann H. Symptomatic infantile polymyoclonus. Z Kinderheilkd 1971;111:240-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moe PG, Nellhaus G. Infantile polymyoclonia-opsoclonus syndrome and neural crest tumors. Neurology 1970;20:756-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bray PF, Ziter FA, Lahey ME, et al. The coincidence of neuroblastoma and acute cerebellar encephalopathy. J Pediatr 1969;75:983-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brissaud HE, Beauvais P. Opsoclonus and neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 1969;280:1242. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lemerle J, Lemerle M, Aicardi J, et al. Report of 3 cases of association of an oculo-cerebello-myoclonic syndrome with a neuroblastoma. Arch Fr Pediatr 1969;26:547-58. [PubMed]

- Solomon GE, Chutorian AM. Opsoclonus and occult neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 1968;279:475-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davidson M, Tolentino Y, Sapir S. Opsoclonus and neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 1968;279:948. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Altman AJ, Baehner RL. Favorable prognosis for survival in children with coincident opso-myoclonus and neuroblastoma. Cancer 1976;37:846-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suita S, Tajiri T, Sera Y, et al. The characteristics of mediastinal neuroblastoma. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2000;10:353-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Demir HA, Yalçin B, Büyükpamukçu N, et al. Thoracic neuroblastic tumors in childhood. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010;54:885-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koh PS, Raffensperger JG, Berry S, et al. Long-term outcome in children with opsoclonus-myoclonus and ataxia and coincident neuroblastoma. J Pediatr 1994;125:712-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rubie H, Hartmann O, Giron A, et al. Nonmetastatic thoracic neuroblastomas: a review of 40 cases. Med Pediatr Oncol 1991;19:253-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sung KW, Yoo KH, Koo HH, et al. Neuroblastoma originating from extra-abdominal sites: association with favorable clinical and biological features. J Korean Med Sci 2009;24:461-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brodeur GM. Spontaneous regression of neuroblastoma. Cell Tissue Res 2018;372:277-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rothenberg AB, Berdon WE, D'Angio GJ, et al. The association between neuroblastoma and opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome: a historical review. Pediatr Radiol 2009;39:723-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Storstein A, Krossnes BK, Vedeler CA. Morphological and immunohistochemical characterization of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration associated with Yo antibodies. Acta Neurol Scand 2009;120:64-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McKeon A, Tracy JA, Pittock SJ, et al. Purkinje cell cytoplasmic autoantibody type 1 accompaniments: the cerebellum and beyond. Arch Neurol 2011;68:1282-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McKeon A, Pittock SJ. Paraneoplastic encephalomyelopathies: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol 2011;122:381-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Budde-Steffen C, Anderson NE, Rosenblum MK, et al. An antineuronal autoantibody in paraneoplastic opsoclonus. Ann Neurol 1988;23:528-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lennon VA. Paraneoplastic autoantibodies: the case for a descriptive generic nomenclature. Neurology 1994;44:2236-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Graus F, Rowe G, Fueyo J, et al. The neuronal nuclear antigen recognized by the human anti-Ri autoantibody is expressed in central but not peripheral nervous system neurons. Neurosci Lett 1993;150:212-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Altermatt HJ, Rodriguez M, Scheithauer BW, et al. Paraneoplastic anti-Purkinje and type I anti-neuronal nuclear autoantibodies bind selectively to central, peripheral, and autonomic nervous system cells. Lab Invest 1991;65:412-20. [PubMed]

- Benyahia B, Liblau R, Merle-Béral H, et al. Cell-mediated autoimmunity in paraneoplastic neurological syndromes with anti-Hu antibodies. Ann Neurol 1999;45:162-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schobinger-Clément S, Gerber HA, Stallmach T. Autoaggressive inflammation of the myenteric plexus resulting in intestinal pseudoobstruction. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:602-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wildhaber B, Niggli F, Bergsträsser E, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in ganglioneuroblastoma: contrasting symptoms of constipation and diarrhoea. Eur J Pediatr 2003;162:511-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Vuurden DG, Plötz FB, de Jong M, et al. Therapeutic total plasma exchange in a child with neuroblastoma-related anti-Hu syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2005;20:1655-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Giorgio R, Bovara M, Barbara G, et al. Anti-HuD-induced neuronal apoptosis underlying paraneoplastic gut dysmotility. Gastroenterology 2003;125:70-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper R, Khakoo Y, Matthay KK, et al. Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome in neuroblastoma: histopathologic features-a report from the Children's Cancer Group. Med Pediatr Oncol 2001;36:623-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pranzatelli MR, Travelstead AL, Tate ED, et al. B- and T-cell markers in opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome: immunophenotyping of CSF lymphocytes. Neurology 2004;62:1526-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Russo C, Cohn SL, Petruzzi MJ, et al. Long-term neurologic outcome in children with opsoclonus-myoclonus associated with neuroblastoma: a report from the Pediatric Oncology Group. Med Pediatr Oncol 1997;28:284-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]