DRD1 and DRD4 are differentially expressed in breast tumors and breast cancer stem cells: pharmacological implications

Introduction

The family of dopamine receptors (DRs) includes five G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)—DRD1, DRD2, DRD3, DRD4 and DRD5—with different anatomical distribution, expression levels, dopamine affinity, signal transduction, and effector targets (1,2). Changes in the expression and/or function of DRs have been reported in multiple neurological pathologies (3,4), but their role in cancer progression is still unclear (2).

In breast cancer, the most frequent cancer type in women worldwide (5), the role of DRs is controversial. The idea that DRs expression favors more aggressive phenotypes is supported by the fact that expression of DRD1 and DRD2 are increased in malignant tumors compared to benign ones and normal mammary tissue (6). Furthermore, patients with DRD1 overexpression have reduced overall and recurrence-free survival compared to patients with no expression (7). Accordingly, exposure of triple-negative breast cancer cells to a DRD1 selective antagonist inhibits proliferation and motility, and triggers cell death (8). Similarly, it has been reported that DRD2 is overexpressed in human breast cancer samples and cell lines, and its downregulation suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in vitro (6). However, the pharmacological activation of DRD2 lacks of effect in mouse models of triple-negative breast tumors (7).

On the other hand, there is also evidence supporting an anti-tumoral role of DRs. For example, exogenous administration of dopamine reduces tumor growth and angiogenesis in animal models (9-11). DRD1 agonists reduce viability and promote apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells, reducing xenotransplant growth (7), and reduce migration, invasion and lung metastasis (12). In agreement, DRD1 antagonists promote xenotransplant growth (10).

Given that previous studies have focused on DRD1 and DRD2, herein we analyzed the expression of all five DRs in breast tumors and breast cancer cell lines using public datasets. Our results showed that DRD3 and DRD5 transcripts are undetectable in most of the samples, but DRD1, DRD2 and DRD4 transcripts were expressed with high variability. Experimental quantification of DRD1, DRD2 and DRD4 proteins in MCF-7 (luminal) and MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative) cells showed that DRD4 is consistently expressed in the cell membrane, but DRD1 was found only intracellularly. To analyze the possible differential expression of DRs in subsets of cancer cells, we employed the previously reported SORE6 reporter system (13) and evaluated the membrane expression of DRs in cancer stem cells (CSCs) and tumor-bulk cells. The expression of DRD1 was increased but that of DRD4 was reduced in CSCs from of both cell lines, suggesting that DRs may have relevance in stemness control. To address such possibility, we treated breast cancer cells with agonists or antagonists of DRs. Subtoxic concentrations of DRD1-targeting drugs did not induced significant changes in the CSCs fraction, but DRD4 inhibition might increase such fraction. Finally, we identified that DRD4 pharmacological inhibition reduced the cell migration of MDA-MB-231 cells, indicating that the role of DRD4 in each breast cancer cell subpopulation requires further analysis. We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-783/rc).

Methods

Analysis of gene expression and clinical outcome

Comparison of expression of DRs in breast tumors versus normal tissue and analyses of the relationship between DRs expression with clinical outcome were analyzed in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)/Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEX) cohort using the UCSC Xena browser (14). Analysis of coexpression correlation in the same cohort was performed using cBioPortal (15,16). Expression of genes of interest in breast cancer cell lines was assessed using expression data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) (17) accessed through Cancer Dependency Map (DepMap) portal (18).

Cell lines

We employed MDA-MB-231 (HTB-26) and MCF-7 (HTB-22) breast cancer cells; both obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Only cells below passage 20 were employed for our experiments. MDA-MB-231 cells were routinely cultured in Leibovitz’s L-15 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 ℃, whereas MCF-7 cells were maintained in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) with 10% FBS and 0.01 mg/mL human recombinant insulin, at 37 ℃ in an atmosphere with 5% CO2. Lentivirus generation was performed in HEK293 cells (CRL-1573, ATCC) cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS, at 37 ℃ in an atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Compounds and treatments

We employed the compounds SKF-38393 (sc-264306, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Quinpirole (Q102, Sigma-Aldrich), SCH-23390 (D054, Sigma-Aldrich), and Haloperidol (sc-203596, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Stock solutions of SKF-38393, Quinpirole, and SCH-23390 were prepared in Mili Q water, whereas Haloperidol was dissolved in DMSO (D4540, Sigma-Aldrich). Solutions were stored at −70 ℃ with light protection until usage.

Identification of CSCs

Quantification of the CSC-subpopulation was performed in sublines generated by lentiviral transduction of a reporter system containing six concatenated repeats of SOX2/OCT4 response elements driving the expression of destabilized green fluorescent protein (SORE6-GFP) (13). A construction with a minimal cytomegalovirus promoter (mCMV)-GFP was employed to generate control cell lines. Both reporter constructions were kindly donated by Dr. L.M. Wakefield (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA). Briefly, MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 cells were exposed to lentiviral supernatants diluted 1:1 in fresh medium for 72 h. Transduced cells were positively selected through a sequential treatment with puromycin 0.5 µg/mL (P4512, Sigma-Aldrich) for additional 72 h and GFP-based cell sorting (FACS Aria II Cell Sorter). The percentage of GFP+ cells after two-dimensional (2D) culture was quantified with the Attune NxT cytometer.

Immunostaining and flow cytometry

Expression of DRs was analyzed using anti-human DRD1 Alexa Fluor 405 (FAB8276V, R&D Systems), anti-human DRD2 Alexa Fluor 647 (sc-5303, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-human DRD4 PE (sc-136169, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). We employed as isotype controls Isotype IgG2a, k Alexa Fluor 405 (IC003V, R&D Systems), Isotype IgG2a, k Alexa Fluor 647 (557857, BD Pharmingen) and Isotype IgG2a, k PE (555574, BD Pharmingen), respectively. Cells were collected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.02 % ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), washed with PBS and stained with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or isotype diluted in PBS with 5% FBS for 30 min at 4 ℃ in the dark. After washing, cells were acquired in a Attune NxT cytometer and data were analyzed with FlowJo software V.10.0. Detection of intracellular DRs was performed in cells that were fixed/ permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (554714, BD Bioscience) and washed with Perm/Wash buffer (554723, BD Bioscience) before incubation with the same antibodies listed above.

Wound healing assay

Migration was evaluated as previously described (19). Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 9×105 cells/well. The next day, the monolayer was wounded with a 200 µL-pipette tip, the wells were washed, and the culture exposed to the corresponding treatments in Leibovitz’s L-15 with 2% FBS and 10 µM Cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside (C1768-100MG, Sigma-Aldrich). The cultures were photographed at time zero and 24 h later in four positions per experimental condition. The percentage of wound closure was calculated by analyzing the micrographs with ImageJ (20) and normalizing the cell-free area in each position against the corresponding area at time zero. The experiments were repeated three independent times.

Statistical analysis

Gene expression (RNAseq) data were compared by Welch’s t-test. Gene coexpression correlation was assessed by Spearman test and Pearson test. Survival curves were analyzed by log-rank test. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of SORE6-GFP+ and SORE6-GFP− cell subpopulations were compared using Student’s t-test. For assays comparing the effects of multiple concentrations of DR-targeting compounds vs. control (protein expression or migration) we employed ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by Institutional Committee of Ethics and Research, Facultad de Medicina UNAM FMED/CI/RGG/377/2017. Individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Results

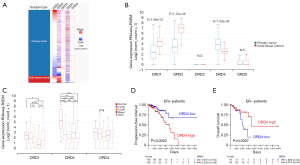

Expression of DRs in breast cancer

To identify changes in DRDs gene expression in breast tumors, we compared the mRNA expression of all five DRDs in tumors vs. normal tissue using data from TCGA/ GTEx database. DRD3 and DRD5 were expressed at very low levels in primary breast tumors and normal mammary tissue. DRD1 and DRD2 mRNA levels were reduced in breast tumors compared to normal tissue. On the other hand, DRD4 expression was significantly higher in tumor samples (Figure 1A,1B).

In the TCGA cohort, we found differences in DRDs expression by molecular subtype (Figure 1C). DRD1 was underexpressed in basal tumors compared with all other subtypes but luminal B. DRD2 mRNA was overexpressed in normal-like and basal tumors. For DRD4, we found significant differences only between luminal subtypes. In the same cohort, DRD1 or DRD2 expression did not correlated with changes in clinical outcome (data not shown). On the other hand, increased DRD4 expression correlated with decreased progression-free interval in patients with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive tumors (Figure 1D) and augmented survival time in patients with ER-negative tumors (Figure 1E). These results suggest that DRD4 expression plays a dual role depending on the ER status. However, we found the DRD4 expression showed a weak, but statistically significant, negative correlation with ESR1 (ER) expression and negligible correlation with ERBB2 (HER2) or progesterone receptor (PGR) (Figure S1).

DRs expression in breast cancer cell lines

Then, we analyzed the expression of DRDs genes in breast cancer cell lines using public data from the CCLE (17). In agreement with the TCGA data, DRD3 and DRD5 transcripts were undetectable in most of the cell lines studied. Particularly, in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, the two cell lines employed in this work, both genes were not expressed (Figure 2A) and, therefore, were not considered for further studies. DRD2 was expressed in most the cell lines analyzed, whereas DRD4 was detected in all the cell lines and had a higher average expression. DRD1 expression showed large variability, with very high transcript number in MCF-7 and no expression at all in MDA-MB-231.

The expression of the proteins DRD1, DRD2, and DRD4 in the membrane of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells was assessed by flow cytometry. DRD1 and DRD2 were not detected in the two cell lines studied (Figure 2B,2C) but they were found in the positive controls U87-MG and HEPG2 cells (Figure S2). On the other hand, membrane DRD4 was detected in both breast cancer cell lines (Figure 2B,2C), as well as in the positive control HEPG2 (Figure S2).

Given that DRD1 transcript has been detected by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) (21) and Western blot in MCF-7 cells (7), we analyzed the expression of DRD1, DRD2 and DRD4 in permeabilized MCF-7 cells. We found that DRD1 and DRD4, but not DRD2, were indeed located intracellularly (Figure S3).

DRD1 and DRD4 are differentially expressed in breast CSCs

To analyze the differential expression of DRDs in breast CSCs, we employed sublines stably expressing the reporter system SORE6-GFP. In those cells, GFP is expressed in cells with transcriptionally active SOX2/OCT4, corresponding to the CSCs subpopulation (13). We found that approximately 4% and 9% of the cells were GFP+ in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, respectively (Figure 3A). When comparing the expression of DRs in CSCs with the rest of the population, we found a discreate but significant increase in the expression of DRD1 in the SORE6-GFP+ fraction for both cell lines. We also found that DRD4 expression is reduced in SORE6-GFP+ cells, which was statistically significant for MCF-7 (Figure 3B,3C). These results suggest that DRD1 and DRD4 are differentially expressed in stem vs. non-stem cells.

Effect of DRD-targeting drugs in the CSCs pool

The relevance of the DRs in the CSCs biology was assessed by pharmacological activation or inhibition of the receptors. MCF-7 (Figure 4A) and MDA-MB-231 (Figure 4B) cells were treated either with: (I) the DRD1/DRD5 agonist SKF-38393; (II) the DRD1/DRD5 antagonist SCH-23390; (III) the DRD2/DRD3/DRD4 agonist Quinpirole; or (IV) the DRD2/DRD3/DRD4 antagonist Haloperidol. Although any of the treatments induced significant changes in the SORE6-GFP+ fraction, we identified a tendency to increase in MDA-MB-231 cell treated with Haloperidol (Figure 4B). The four drugs lacked cytotoxicity at the concentrations evaluated, as demonstrated by the quantification of the 7-aminoactinomycin D-positive (7AAD+) fraction (Figure 4C,4D).

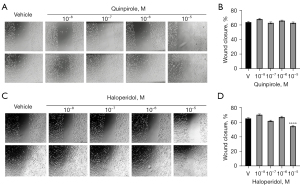

DRD4 inhibition reduces migration in MDA-MB-231 cells

Previous reports show that DR-modulation modifies the migration of breast cancer cells (8,12). Given that DRD4, but not DRD1 or DRD2, was expressed in the highly migratory cell line MDA-MB-231, we analyzed the effect of the DRD4-targeting drugs Quinpirole and Haloperidol in cell migration (Figure 5). DRD4 inhibition with 10 µM Haloperidol reduced the cell migration (Figure 5C,5D). No changes were observed after Quinpirole treatment (Figure 5A,5B).

Discussion

Expression of DRs has been found altered in multiple types of cancers (2) and several authors have proposed that DRs may become therapeutic targets for improving clinical responses in cancer patients (22-25). Herein, we identified that DRD1 is downregulated in human breast tumors. These data agree with a previous work reporting that only one third of human breast tumors have clear immunoreactivity to anti-DRD1, and that such patients have reduced overall survival (7). Our analysis of TCGA data indicate that DRD1 is underexpressed in basal tumors, which contrast with the reported importance of DRD1-mediated signaling in triple-negative breast cancer cells (7,8,26). In agreement, the triple-negative model selected for this study, the cell line MDA-MB-231, did not express DRD1 mRNA nor DRD1 protein, suggesting that this cell line is not a good model for studying the role of DRD1 in breast cancer biology. Surprisingly, in the luminal cell line MCF-7 DRD1 protein was detected only intracellularly. As other membrane GPCRs, DRD1 requires membranal localization to be activated by extracellular agonists (27). Thus, further studies must investigate if the inadequate translocation of DRD1 occurs in other luminal models and if intracellular DRD1 overexpression plays a role of in breast cancer cell biology.

The expression of DRD1 was increased in the SORE6-GFP+ cells, which corresponds to CSCs (13). CSCs are key in the development of drug resistance and metastasis (28,29) and characterizing the signals that influence their phenotype is a major goal in breast cancer research (30). Previous studies reported that DRD1 activation by agonists reduce the CSC-pool in Adriamycin-resistant MCF-7 (10) and MDA-MB-231 (12) cells. Those reports differ from our findings, since the use of the DRD1/DRD5 agonist SKF-38393 in this work did not change the SORE6-GFP+ fraction, even a micromolar concentrations. The disparities could be caused by the usage of different methods and experimental endpoints. For example, Yang et al. quantified the CSCs fraction using the CD44+/CD24− immunophenotype and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity (12). Nevertheless, our results do not support the idea that pharmacological modulation of DRD1 could be beneficial for breast cancer patients.

We also found that DRD4 is overexpressed in breast tumors and can be detected in the membrane of both cellular models employed. However, SORE6-GFP+ cells had reduced DRD4 expression compared with the rest of the cancer cells. These results correlate with previous works reporting that female schizophrenic patients treated with Haloperidol or other DRD2/DRD4 antagonists have a higher risk of developing breast cancer (31,32). On the other hand, the drug thioridazine, another DRD2 antagonist with low selectivity, is active against breast, leukemia, and colorectal CSCs (33,34), but it is unclear if those effects are caused by DR inhibition or by modulation of other receptors. In our experiments, Haloperidol produced a non-significant increase in the SORE6-GFP+ fraction of MDA-MB-231 cells, supporting the hypothesis that DRD4 inhibition promotes the acquisition of a more malignant phenotype and worst clinical outcome. Surprisingly, DRD4 underexpression correlated with poor clinical only in ER-negative tumors, but had an opposite trend in ER-positive tumors. This dual role of DRD4 and the relationship with ER status requires further studies.

Given that DRD4 is expressed not only in the CSC-pool but also in tumor-bulk cells, we evaluated the effect of pharmacological modulation of the receptor in the migration of MDA-MB-231 cells. DRD4 inhibition with Haloperidol decreased migration in wound healing assays. In agreement, the drug SYA013, an Haloperidol analog, suppresses cell migration and invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells (35). However, SYA013 also induces apoptosis, whereas we did not detect increased cell death in cultures exposed to Haloperidol.

Conclusions

Pharmacological modulation of DRD1 in MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells seems to be irrelevant in the maintenance of stemness, even when CSCs but not tumor-bulk cells have detectable levels of the receptor in the cell membrane. On the contrary, DRD4 reduced expression in breast CSCs or its inhibition by Haloperidol favors CSC-pool expansion. DRD4 inhibition can also reduce cell migration, indicating that DRD4 plays different roles in stem and non-stem breast cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

The results shown in Figure 1 and Figure S1 are in whole or part based upon data generated by the TCGA Research Network: https://www.cancer.gov/tcga.

Funding: This work was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-783/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-783/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-783/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-783/coif). MAVV reports that research funding and APC was/will be provided by Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, employer of MAVV. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by Institutional Committee of Ethics and Research, Facultad de Medicina UNAM FMED/CI/RGG/377/2017. Individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2011;63:182-217. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosas-Cruz A, Salinas-Jazmín N, Velázquez MAV. Dopamine Receptors in Cancer: Are They Valid Therapeutic Targets? Technol Cancer Res Treat 2021;20:15330338211027913. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mishra A, Singh S, Shukla S. Physiological and Functional Basis of Dopamine Receptors and Their Role in Neurogenesis: Possible Implication for Parkinson's disease. J Exp Neurosci 2018;12:1179069518779829. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vallone D, Picetti R, Borrelli E. Structure and function of dopamine receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2000;24:125-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, et al. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;5:66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gholipour N, Ohradanova-Repic A, Ahangari G. A novel report of MiR-4301 induces cell apoptosis by negatively regulating DRD2 expression in human breast cancer cells. J Cell Biochem 2018;119:6408-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borcherding DC, Tong W, Hugo ER, et al. Expression and therapeutic targeting of dopamine receptor-1 (D1R) in breast cancer. Oncogene 2016;35:3103-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Minami K, Liu S, Liu Y, et al. Inhibitory Effects of Dopamine Receptor D1 Agonist on Mammary Tumor and Bone Metastasis. Sci Rep 2017;7:45686. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters MAM, Meijer C, Fehrmann RSN, et al. Serotonin and Dopamine Receptor Expression in Solid Tumours Including Rare Cancers. Pathol Oncol Res 2020;26:1539-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang S, Mou Z, Ma Y, et al. Dopamine enhances the response of sunitinib in the treatment of drug-resistant breast cancer: Involvement of eradicating cancer stem-like cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2015;95:98-109. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sarkar C, Chakroborty D, Chowdhury UR, et al. Dopamine increases the efficacy of anticancer drugs in breast and colon cancer preclinical models. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:2502-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang L, Yao Y, Yong L, et al. Dopamine D1 receptor agonists inhibit lung metastasis of breast cancer reducing cancer stemness. Eur J Pharmacol 2019;859:172499. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang B, Raviv A, Esposito D, et al. A flexible reporter system for direct observation and isolation of cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 2015;4:155-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldman MJ, Craft B, Hastie M, et al. Visualizing and interpreting cancer genomics data via the Xena platform. Nat Biotechnol 2020;38:675-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 2013;6:pl1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2012;2:401-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghandi M, Huang FW, Jané-Valbuena J, et al. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature 2019;569:503-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boehm JS, Garnett MJ, Adams DJ, et al. Cancer research needs a better map. Nature 2021;589:514-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Velázquez MA, Agramonte-Hevia J, Barrera D, et al. 4-Hydroxycoumarin disorganizes the actin cytoskeleton in B16-F10 melanoma cells but not in B82 fibroblasts, decreasing their adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins and motility. Cancer Lett 2003;198:179-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012;9:671-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pornour M, Ahangari G, Hejazi SH, et al. Dopamine receptor gene (DRD1-DRD5) expression changes as stress factors associated with breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:10339-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Wang ZB, Luo C, et al. The Prospective Value of Dopamine Receptors on Bio-Behavior of Tumor. J Cancer 2019;10:1622-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weissenrieder JS, Neighbors JD, Mailman RB, et al. Cancer and the Dopamine D2 Receptor: A Pharmacological Perspective. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2019;370:111-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roney MSI, Park SK. Antipsychotic dopamine receptor antagonists, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Arch Pharm Res 2018;41:384-408. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JK, Nam DH, Lee J. Repurposing antipsychotics as glioblastoma therapeutics: Potentials and challenges. Oncol Lett 2016;11:1281-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tu YS, He J, Liu H, et al. The Imipridone ONC201 Induces Apoptosis and Overcomes Chemotherapy Resistance by Up-Regulation of Bim in Multiple Myeloma. Neoplasia 2017;19:772-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martinez VJ, Asico LD, Jose PA, et al. Lipid Rafts and Dopamine Receptor Signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:8909. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Velázquez MA, Homsi N, De La Fuente M, et al. Breast cancer stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012;44:573-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Velázquez MA, Popov VM, Lisanti MP, et al. The role of breast cancer stem cells in metastasis and therapeutic implications. Am J Pathol 2011;179:2-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Velázquez MA, Velázquez-Quesada I, Vásquez-Bochm LX, et al. Targeting Breast Cancer Stem Cells: A Methodological Perspective. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2019;14:389-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu Chou AI, Wang YC, Lin CL, et al. Female schizophrenia patients and risk of breast cancer: A population-based cohort study. Schizophr Res 2017;188:165-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Hert M, Peuskens J, Sabbe T, et al. Relationship between prolactin, breast cancer risk, and antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: a critical review. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016;133:5-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sachlos E, Risueño RM, Laronde S, et al. Identification of drugs including a dopamine receptor antagonist that selectively target cancer stem cells. Cell 2012;149:1284-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang C, Gong P, Liu P, et al. Thioridazine elicits potent antitumor effects in colorectal cancer stem cells. Oncol Rep 2017;37:1168-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asong GM, Amissah F, Voshavar C, et al. A Mechanistic Investigation on the Anticancer Properties of SYA013, a Homopiperazine Analogue of Haloperidol with Activity against Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. ACS Omega 2020;5:32907-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]