Perspective towards the clinical application of eribulin in soft tissue sarcomas

Introduction

Eribulin mesilate (trade name Halaven®) is a synthetic macrocyclic analogue of the marine halichondrin B. This anticancer drug was approved both by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency in 2010, for treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer who have received at least two prior chemotherapy regimens for late-stage disease, including both anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapies (1), and recently, for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic liposarcoma in patients who received prior at least one line of systemic therapy including chemotherapy based on anthracyclines (2).

Eribulin—mechanism of action

Eribulin has with unique mechanism of action leading to the inhibition of microtubule dynamics, which is distinct from that of other tubulin-targeted drugs. Eribulin binds predominantly to a small number of high affinity sites at the plus ends of existing microtubules, which exerts its anticancer effects by triggering apoptosis of cancer cells following prolonged and irreversible mitotic blockade (1,3) In soft tissue sarcomas (STS) eribulin has lead also to tumor vasculature remodeling, what could induce differentiation of tumor cells (4).

STS

Sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors comprising more than 60 subtypes, which are clinically and biologically different. The standard first-line therapy for advanced STS is doxorubicin, either as monotherapy or in combination with ifosfamide. A limited number of drugs have shown activity in treatment-refractory disease, including dacarbazine, gemcitabine +/− docetaxel, trabectedin, or pazopanib (5,6). Due to the rarity of these tumors, routinely clinical trials in sarcoma included all subtypes and they are mainly initiated by academic research groups. So far, there have been only few phase III studies investigating the efficacy of target therapies in patients with advanced L-sarcomas (leiomyosarcomas or liposarcomas). None of these studies reported a significant difference in overall survival between the treatment groups.

Pivotal phase III trial with eribulin in previously treated advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma

Data supporting approval of eribulin in liposarcoma comes from a phase 3 randomized, open-label clinical trial reported by Schöffski et al. (6). Based on data from phase 2 study, where only the strata for leiomyosarcoma and liposarcoma met the primary endpoint of progression-free-survival at 12 weeks (2), in the phase 3 study patients with advanced STS limited to these subtypes were included, after failure of at least two previous systemic regimens for advanced disease (including anthracycline). The primary endpoint was overall survival and 446 patients were randomly (1:1) assigned to arm receiving eribulin mesilate (1.4 mg/m2) intravenously on days 1, 8 (n=228), or dacarbazine (850 mg/m2, 1,000 mg/m2, or 1,200 mg/m2) intravenously on day 1, every 21 days (n=224) until disease progression or unaccepted toxicity. The doses of dacarbazine were investigator’s choice. Fifty percent of patients in eribulin arm received more than two previous lines of systemic therapy, 32% of patients had liposarcoma.

Toxicity profile of eribulin was consistent with investigator’s brochure, and no unexpected or new safety findings were observed. In this study, the most common adverse events in eribulin arm were: neutropenia, asthenia/fatigue, nausea, alopecia and constipation. Grade 3 or higher adverse events were more common in eribulin arm [152 (67%)]. There was one death related to eribulin, 6% of patients finished eribulin due to toxicity.

The findings from this study showed a median overall survival improvement of 2.6 months (13.5 vs. 11.5 months) in all patients treated with eribulin versus dacarbazine [hazard ratio (HR), 0.768; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.618–0.954; P=0.017]. The subgroup analysis suggested that the survival benefit with eribulin was mainly observed in patients with liposarcoma (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.35–0.75; median survival 15.6 vs. 8.4 months), but the study was not powered for drawing final conclusions from subgroup analysis. Despite overall survival benefit there was no significant difference in progression free survival between treatment groups, what is difficult to explain.

There are some limitations of the study, dacarbazine was chosen as the active control despite its modest efficacy in sarcomas at this stage, its dose was different (850–1,200 per m2) and no other effective treatment options such as trabectedin or pazopanib (excluding liposarcomas) were allowed. Although control group outperformed the overall survival expectations, still the eribulin cohort showed significantly better outcomes. Based on these phase 3 results, eribulin was approved in refractory liposarcoma, and cannot be prescribed in clinical practice to other sarcoma subtypes.

The landscape of systemic therapy of advanced L-sarcomas

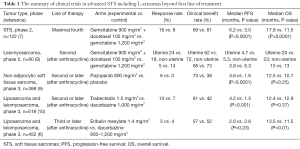

L-sarcomas comprise the interesting heterogenous group of STS—liposarcomas (several subtypes) and leiomyosarcomas. There were often studied together in several trials, but still limited options of systemic therapy exist beyond the first line of treatment. The comparison of the recent trials in STS including L-sarcomas is presented in Table 1. To summarize, pazopanib is approved for leiomyosarcomas but not for liposarcomas, trabectedin is approved for both of the L-sarcomas, and eribulin is approved for liposarcomas but not leiomyosarcomas.

Full table

The phase 3 PALETTE study compared an activity of a multitargeted tyrosine-kinase inhibitor—pazopanib with placebo in patients with metastatic treatment refractory STS excluding liposarcoma subtype. It has demonstrated significant progression-free survival in pazopanib arm vs. placebo (4.6 vs. 1.6 months; HR, 0,31; P<0.0001; with similar range of benefit in leiomyosarcoma subgroup), but without significant difference in median overall survival. Based on the results of this trial pazopanib is approved for treatment of non-adipocytic STS (9).

Gemcitabine +/− docetaxel has been studied in several trials, but only the study with a Bayesian adaptive randomization design demonstrated overall survival improvement with median survival of 12.9 months in combination arm as compared to 11.5 months in the gemcitabine only arm (7). In French Sarcoma Group phase II trial in treatment refractory leiomyosarcoma population there was no benefit of combination arm relative to single-drug gemcitabine, and the drug activity was clearly better in uterine leiomyosarcoma group (8).

For refractory L-sarcomas in similar to eribulin trial population, Demetri et al. (10) conducted a randomised phase 3 trial on 518 patients, which compared trabectedin with dacarbazine. This study, in contrast to the Schoffski’s trial, showed a significant improvement in progression-free survival in trabectedin cohort (4.2 vs. 1.5 months in control arm, P<0.001), but no significant difference in overall survival. Benefit was seen in both uterine and non-uterine leiomyosarcomas and in all liposarcoma subtypes, although the benefit compared with dacarbazine was most pronounced (median PFS 5.6 vs. 1.5 months) in the myxoid/round cell liposarcoma subtype (which seems to be particularly sensitive to trabectedin). In both studies, the number of objective responses was low, so patients should be counselled that such treatment can rather control disease than shrink tumors. The toxicity profiles of both eribulin and trabectedin are manageable. Some patients might prefer eribulin, in view of its survival benefits.

Conclusions

The findings from the trial suggest that eribulin might be another important treatment option in armamentarium for patients with previously treated liposarcoma. There are currently limited treatment options available, but now, we are a step closer to being able to offer them a treatment with a proven overall survival benefit after decades of no progress. Interesting (after encouraging phase 2 trial results) (11) phase 3 trial comparing doxorubicin without and with olaratumab is underway. Eribulin is the first-ever single agent therapy to show such a survival benefit in sarcomas, which makes this trial even more important for patients and clinicians worldwide.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Translational Cancer Research. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2016.10.36). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Eribulin prescribing information. Accessed on August 29, 2016. Available online: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/201532s015lbl.pdf?et_cid=37339842&et_rid=907466112&linkid=http%3a%2f%2fwww.accessdata.fda.gov%2fdrugsatfda_docs%2flabel%2f2016%2f201532s015lbl.pdf

- Schöffski P, Ray-Coquard IL, Cioffi A, et al. Activity of eribulin mesylate in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma: a phase 2 study in four independent histological subtypes. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:1045-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jordan MA, Kamath K, Manna T, et al. The primary antimitotic mechanism of action of the synthetic halichondrin E7389 is suppression of microtubule growth. Mol Cancer Ther 2005;4:1086-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawano S, Asano M, Adachi Y, et al. Antimitotic and Non-mitotic Effects of Eribulin Mesilate in Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Anticancer Res 2016;36:1553-61. [PubMed]

- Ratan R, Patel SR. Chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer 2016;122:2952-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schöffski P, Chawla S, Maki RG, et al. Eribulin versus dacarbazine in previously treated patients with advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma: a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;387:1629-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maki RG, Wathen JK, Patel SR, et al. Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine and docetaxel compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcomas: results of sarcoma alliance for research through collaboration study 002 J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2755-63. [corrected]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pautier P, Floquet A, Penel N, et al. Randomized multicenter and stratified phase II study of gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine and docetaxel in patients with metastatic or relapsed leiomyosarcomas: a Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (FNCLCC) French Sarcoma Group Study (TAXOGEM study). Oncologist 2012;17:1213-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012;379:1879-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Jones RL, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Trabectedin or Dacarbazine for Metastatic Liposarcoma or Leiomyosarcoma After Failure of Conventional Chemotherapy: Results of a Phase III Randomized Multicenter Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:786-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tap WD, Jones RL, Van Tine BA, et al. Olaratumab and doxorubicin versus doxorubicin alone for treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma: an open-label phase 1b and randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet 2016;388:488-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]